Today I’m calling Brooklyn-based media artist Rachel Rossin.

Born in 1987, Rachel grew up in South Florida, where she lived in the shadow of natural disaster. This sense of anxiety—a kind of dread for nature’s ferocious side—still colors Rachel’s work. By age 8, Rachel was already painting and writing computer code, and she eventually began experimenting with virtual reality and digital art.

Welcome, Rachel.

Rachel Rossin: Hi, Barbara. Thank you for the introduction.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: I thought, to start, perhaps we’d relive some of your art school days. I’ve read you describe your professors as being saintlike people who thought about art differently. Did they instill in you something like a new appreciation for controversy and radicalism in art?

RR: That’s a lovely question. I’m thinking of two professors in particular. The reason I went to Florida State is because it’s free. That was one thing about growing up in Florida: If you come from a middle-class or a lower-income background, you can get higher education for free, so that was why I chose Florida State. It was the only access I had to anything outside of where I grew up. The art department was saintlike there at one of those big football universities. They were in the shadow of the infrastructure, and they did the best they could with little resources. They were people that really believed in the soul of art.

It’s hard to not be jaded in a culture like that, when the emphasis is on something that is so transactional, like the football culture. The entire school is geared and moved around that, in this really political way. The art department faculty had a certain amount of purity to them that I really appreciated. But it wasn’t until I had left and come to New York, where, in the art world, the emphasis on the pedigree was something else; it wasn’t about the actual spirit of the work. It has much more to do with the politics of the way it works. And that’s just how it works. That was something I didn’t appreciate until I looked back on my time there at Florida State, where I had a lot of freedom.

BL: I’m curious, you studied painting, which tends to be known as a traditional form of visual art, but you found your way into virtual reality. I’d love to know what that discovery was like.

RR: It feels more natural for a lot of reasons, which you touched on in your lovely introduction. The role of escapism is important for a lot of young people who grow up feeling alienated from the larger culture, for whatever reason—which is not a unique story for me, but something we see a lot.

In the time that I grew up, I was able to form an alternative narrative with new media. That was already a huge part of the way I was developing and the way my creative self was developing. I was already making virtual worlds, but they just weren’t inside the medium of virtual reality—it was long before the area was called “virtual reality.” The first pieces I was making were using rudimentary AR [augmented reality] with webcam markers. They were kind of between interactive installations and video games.

Works that are built in a video game engine and as an installation are really the two pillars of the type of virtual reality work that I make now. So they just fed each other. When I was making those early works, that was the subject matter for the painting. I was working very much in the same way as when you have a traditional studio practice, and you make maquettes. The virtual landscapes that I was working toward just more accurately represented a psychological space, and that space was where I wanted to be making work from. That served as the content for my beginning pieces.

From there, it was really easy. I was already working in video game engines, so when virtual reality came out, it was a really seamless transition. I was already working in C-Sharp, so I knew the language. These small experiments could be easily ported into a headset.

BL: I know you’ve said that you look at the expansive vistas in paintings by 19th-century artists from the Hudson River School, and you see their paintings as something akin to VR. I’m curious, what impact has their work had on you and what are the similarities between these enormous paintings with vistas of the Hudson River and the work that you’ve done in VR?

RR: I was thinking about plein-air painting. There’s an algorithm called “the painter’s algorithm,” which is an occlusion algorithm. I thought this was a very interesting way of talking about a metaphor for what painting actually is. Cézanne [1839-1906] talks about it, Monet [1840-1926] talks about it, in terms of who the first plein-air painters are. The American painter Robert Henri [1865-1929] very famously talks about it in The Art Spirit [1923], this idea of picking the “plein”—picking the air that you’re making the work from.

The painter’s algorithm was developed as a video game occlusion algorithm. It was made famous by the game Grand Theft Auto as a way to save pixels. The way they can so richly represent reality is because of this advanced algorithm that will choose what you’re actually rendering, instead of everything all at once. And this is now automated. I love this idea of an algorithm being named after something that’s efficient, which isn’t what painting is.

If you were to talk about it in a sort of cynical way, the aesthetics of making something—what is that choice? That choice is a type of efficiency, right? It’s like, in order to accurately represent something—of course you’re not thinking about it when you’re making the work—but in order to fully and most beautifully render this in the way that I see it, there’s this type of efficiency. You start to take out the things that don’t matter, in order to make a proper composition. So, when I’m thinking about those Hudson Valley River painters, the way they talk about plein-air painting, it’s this expansive vista.

I was reading about that algorithm, and then I’d gone on a hike, and the uncanniness of a painting hit me sort of backwards. I had been in a space, it was a Caspar David Friedrich [1774-1840] painting, the Wanderer above the Sea of Fog [1818]. I was on that hike and I had never seen it before in real life. The uncanniness that was crunched in that moment, I realized that’s how I was approaching the virtual landscapes. It’s like the space had come after the image—the space was on top of or just behind the VR glasses, just behind the Oculus Rift.

BL: This brings me to the very first time I wore an Oculus Rift VR headset, which was in 2015 at your exhibition at the Zieher Smith Gallery in New York. For me, the experience was quite magical. I put on the headset, turned my body around 360 degrees, and I was on a virtual tour of your studio with some of your recent paintings. I’m curious, how did that gallery show come about?

Photo and video: Courtesy the artist

RR: You were talking about “the space”—what you were moving through was the source images. Those vistas that you were referring to, the spaces for those paintings was what was being shown in the virtual reality piece. The virtual reality piece was called I Came and Went as a Ghost in Hand, and the show was titled “Lossy,” which has to do with an algorithm for memory. Lossy is basically like an entropic algorithm, but that’s another metaphor just to mean that it’s a way of saving space. It’s what JPEGs and MP3s use and a whole bunch of other types of files. So, the way I was making that show is exactly what we were just talking about, where I was making photogrammetry scans [digitally mapping to measure distances between real objects], which is mostly an architectural device for capturing physical spaces.

I was lying to the computer. I was mashing up renderings to re-create spaces that didn’t exist. And then, next to spaces that did exist—like my studio, my childhood backyard—there were spaces that the paintings were made from that I needed to exist because I wanted them to be in the VR space. There was this sort of push and pull between what was being told to the viewer as truth—which is what the photogrammetry process usually is, it feels very real. When you are in a photogrammetry model, it looks like a scan. I was feeding renderings that were from the space of my imagination, and putting it through that process so that it really did look like a real space.

The way that the virtual reality piece worked is that every viewer’s gaze effectively ate away at the forms by using what is called a “raycast.” In scripting, it is used to determine the line of sight of the viewer. It’s also the way bullet logic is scripted in “shooter” games—it’s the ray that’s literally cast from the gun in order to shoot a bullet. You use it for all types of video game logic, but in my piece, there is an entropic script on the end of that, so that the viewer’s gaze would actually decimate the piece. In my work, it was eating away parts of these memories, these models, the spaces where the paintings were made from, which I would reset every 24 hours. So every viewer had a different perspective; each had a different role in viewing the piece and was taking a part of it with them. There was a consequence to that, to them being there and then leaving something for the viewer after them.

It’s an infinite piece, so you can’t see the same thing twice. On top of what the viewers before you have taken out, that goes back to the exhibition title “Lossy,” which has to do with this entropy script and the exchange of information between my role as the moderator of those paintings, and then the role of the viewer in the VR piece as another entropy moderator. It was about the role of memory and virtual and real spaces, and the materiality of memory and sort of the looseness of memory and each viewer’s subjectivity, and how that plays a role in painting and in translating the paintings.

Rachel Rossin: Stalking the Trace from operating systems on Vimeo

BL: So it’s a little different from the earlier Oculus Rift VR work you did. There are a few recent pieces that I’m curious about. Last year when I did a studio visit, you showed me your Peak Performance series of works, which almost feel like computer aquariums or terrariums. I’m not sure which. I think maybe terrarium because the parts are not swimming or moving, they’re like plants. I know you told me a little bit during the studio visit, but please would say a little now about how that series came about.

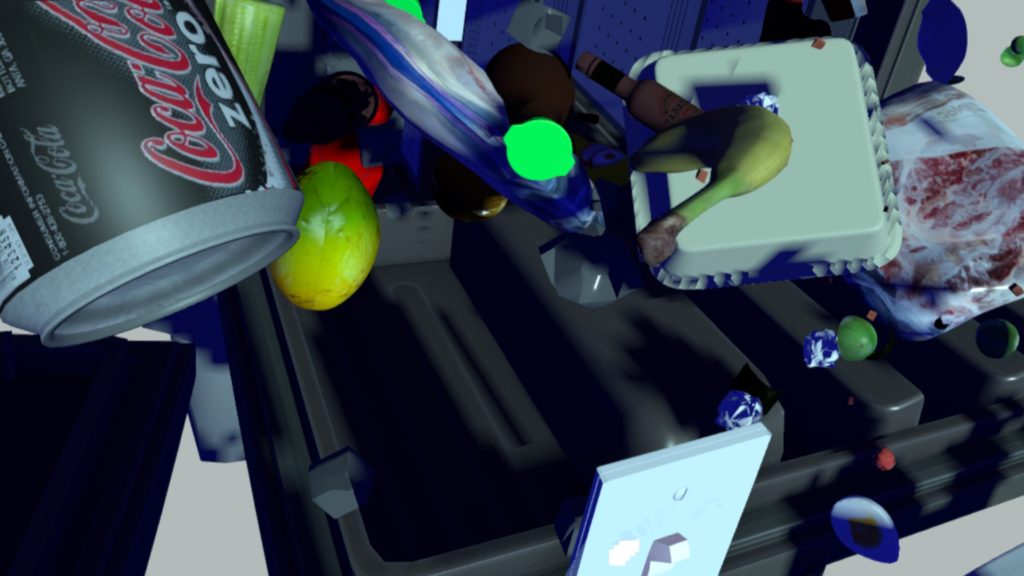

RR: Peak Performance is a show I did at Signal Gallery in Brooklyn, which started as a series of aquarium computers.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

They are large clear containers with computer parts, and are filled with mineral oil.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

There’s this type of gaming PC. It’s something that I did when I was growing up, when I was trying to make the most efficient cooling machine for gaming that you can… You see it a lot now with Bitcoin mining machines. You just need to cool the GPU [graphics processing unit], so that you can overclock it. The GPU is the processor, the graphics processor which is doing all the heavy lifting when you’re gaming or mining Bitcoin, but not when you’re coding. Then if you’re using any sort of simulation-based processing, like if you’re doing any sort of real-time rendering. All of that being done in AI is mostly being crunched in the GPU now.

I mean you can always offload it to the processor. But it’s a visual joke because they’re partially ready-made aquariums, which have to do with the way that I grew up in Florida. They’re mashed together with computer parts that I salvaged and drilled into. But they’re all running off of micro-controllers. They’re closed-loop systems; they’re just performance rigs. They’re computers that are performance rigs, like gaming performance rigs. But they’re visual gags, is really what that series is. This is a visual gag about these useless gaming computers.

Photo: Courtesy the artist

BL: I’ll just ask a quick question about another series of works that you showed me in the studio. I realized that you still pick up a paintbrush, and are still a painter. I saw that you now apply painting on molded plexiglass. In these works, there’s a kind of interactive game-like feel, because they’re very physical.

RR: It’s interesting you say that. The series I’m working on now are these hologram-combine paintings, which are very much in the space of the body and are using the surface there. The paintings are on Plexiglass panels that are pretty large. The ones that I’m working on right now are seven by six feet and they have embedded holographic display fans, which are basically just like really primitive zoetropes. They showed for the first-time last year, and they’re showing in a group show at König Gallery. This is post pandemic, which for Germany is much earlier than for the U.S. And they will be in a show with my gallery in Hamburg, 14a. Those are very much in the physical space—in the language of the body. And then they have these holographic displays, which are AR and that’s directly on top of the painting, embedded directly into the painting and really crunching the uncanny, crunching the reference to where that image is made from.

Molded Plexiglass sculpture with UV print, acrylic paint, and embedded holographic display

Photo and GIF: Courtesy the artist

So, it’s just like talking about the regurgitation of those two spaces, similar to what the show “Lossy” was doing. The Plexiglass series is called the “Hollow Body” series. The way that I made those initially was they’re UV prints made from virtual spaces on Plexiglass. UV is just a way of embedding the pigment on the Plexiglass, so they feel like stained glass substrates. What I do with them after they’ve been printed, and after I’ve painted on top of those surfaces, I soften the plexiglass with a blowtorch and then use my body to mold them so they actually stand on their own as sculpture, as an echo of what my body has left on them.

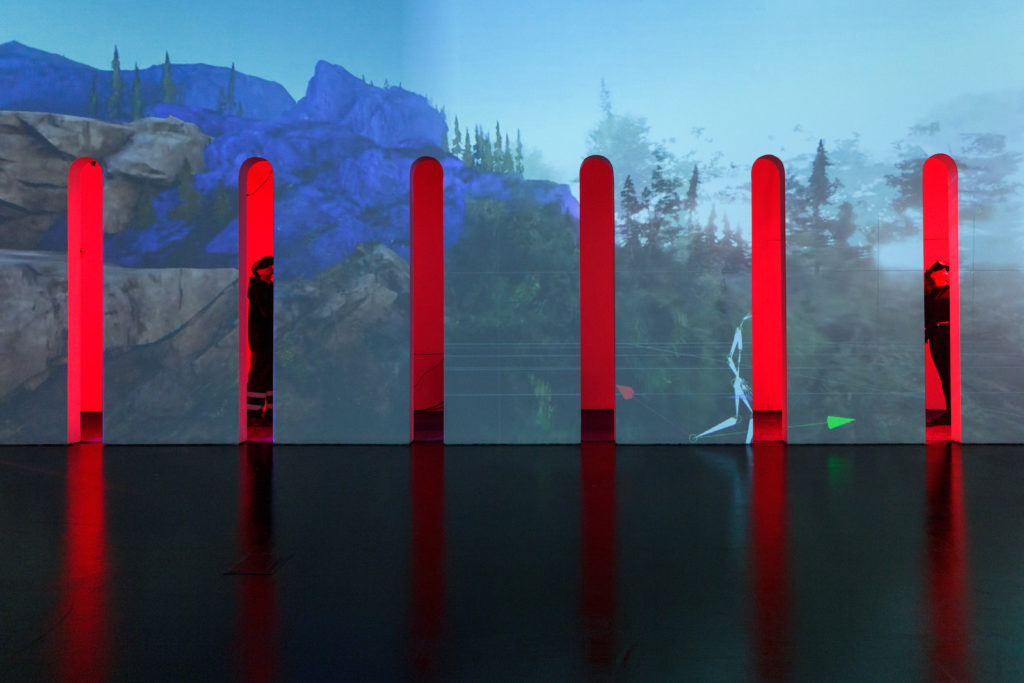

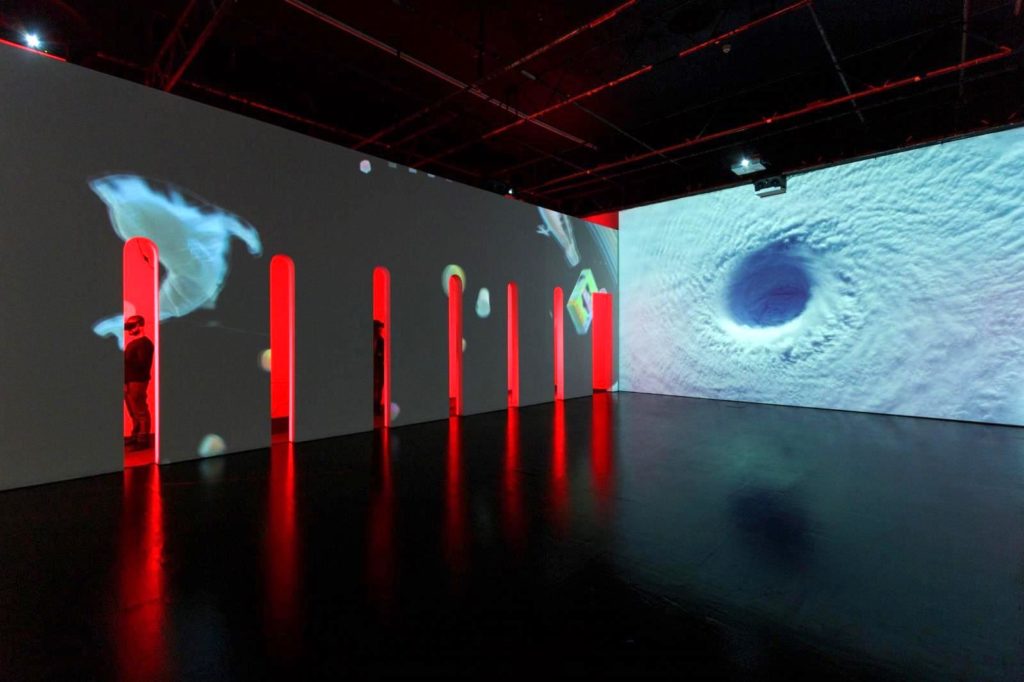

BL: Thank you. Now we’ll move on to Stalking the Trace, which might be considered your magnum opus for now. I’m sure you’ll go on to create another magnum opus. You might call it a VR installation, which was produced by and presented at the Zabludowicz Collection in London, and was also acquired by them.

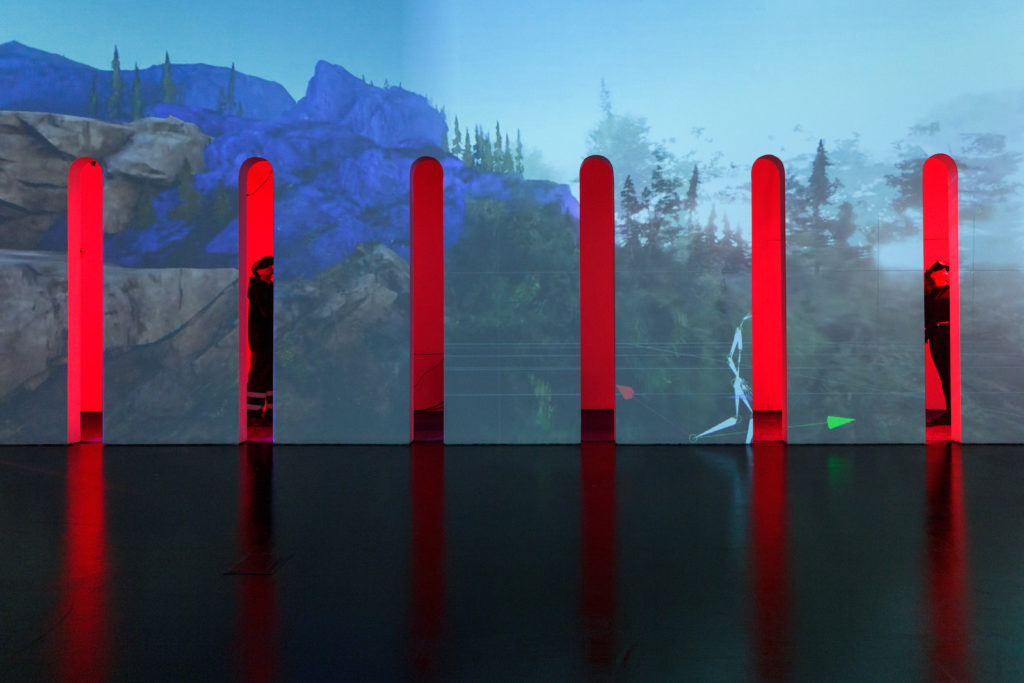

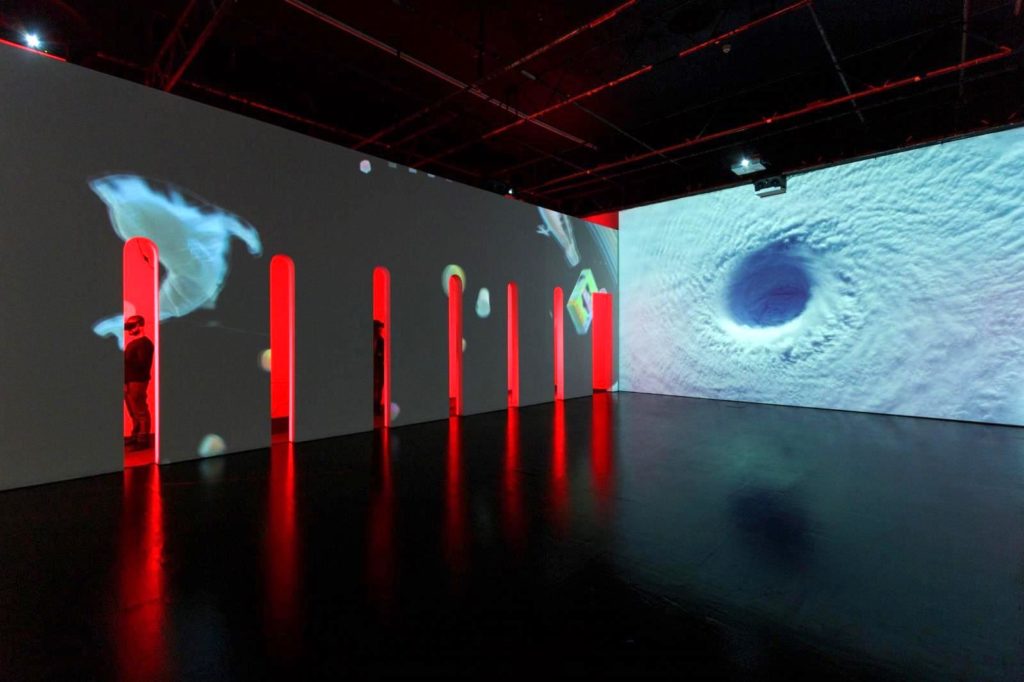

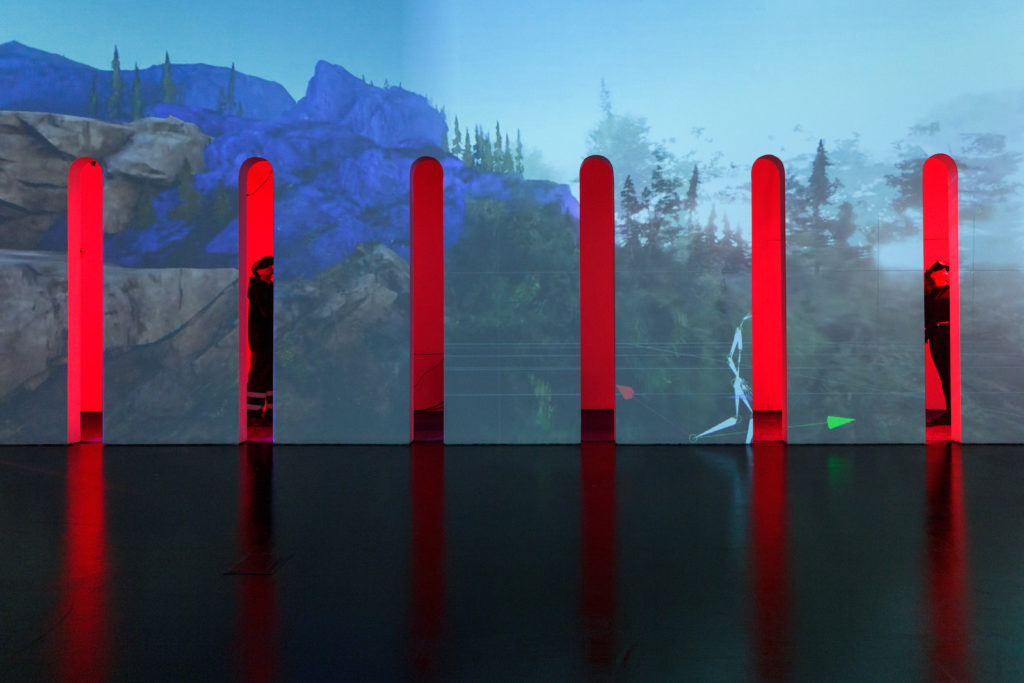

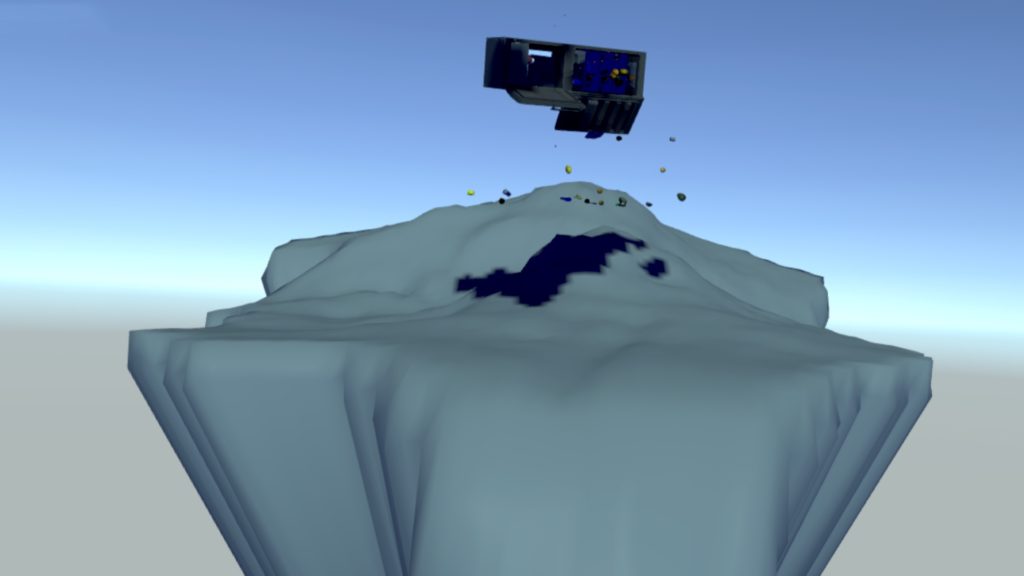

Stalking the Trace is actually quite large and filled the very long Zabludowicz Collection gallery spaces, which I know have a couple of areas off to the sides and behind. Your work offers two levels of viewing experience. First, people standing in the gallery are able to watch and listen to a visual narrator deliver a text written by you, and that’s accompanied by a sound collage, a so-called tone poem that serves to illustrate the VR work. Surrounding the visitor are dense projections of rather turbulent scenes. I know there are cars floating on flooded streets, forests twisting in the wind, and mammoth fireballs that hurdle forward. Some of the imagery is taken from real life, and some of it is simulated with special effects software, and the line between the two is quite blurred. You’ve told me that this piece was responding to the present moment. I would like to know what you mean by that.

Multi-user VR artwork.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

RR: I first started working on that piece in 2017. Well, it was really 2016 when I made the prototype for the VR work, and the VR work was the logic for it. The piece is quite simple. It’s a room-scale VR work, and room-scale just means that the VR piece has an awareness of where you are in the room. I was just using your space, your physical position in the space, and relative to the virtual reality space, being you’re the scrubber of time. So, time becomes a 3D construct. Now there are ways of doing this that are much easier. Back then I was talking to developer friends, and everyone was like, “This is silly and there’s no way of doing this.” It’s much easier now, but then I figured it out after doing some experiments. … Basically what viewers are doing is scrubbing time along the X-axis. Time runs linearly forwards and back, but spatially in 3-Dimensions with the body.

BL: That scrubbing happens when someone in the gallery puts on one of the available headsets, right?

If someone is just standing in the space, various things are happening, but it’s that viewer wearing the VR headset whose body becomes the cursor, and who controls the progress or what you would call the game time of the piece.

RR: Exactly. When you walk into the physical space with arches on the sides, then it’s just an installation with the tone poem.

Multi-user VR artwork.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

That’s the stage it is all happening in, and the multiple layers of catastrophizing inside the VR is because of the action of the headset wearer, who is the arbiter of the piece. Wearing the headset, you’re in control of whether or not you move the piece forwards and backwards through these scenes, through the game time. The physical space acts as the tone poem and the sampling from all of the references that are inside the virtual reality space, which is made from a hybrid of real catastrophe and the glamorization, like the Hollywood special effects software used to make facsimiles of catastrophes. So, there’s this interesting part of the piece that’s using a really advanced simulation for a hurricane and this is quite popular now, especially in Florida. When there’s a giant hurricane coming, you have these weather forecasters standing in the middle of these simulations, while they predict how much destruction is going to be happening to a simulated neighborhood.

Multi-user VR artwork.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

And you have cars that are floating above the forecasters’ heads, and they’re just sort of factually delivering this imminent destruction message. That’s the material of what my piece is playing with; it has a lot to do with the idea of magical thinking through the way that we use the software to sort of expect, and then prepare for catastrophe. Some of the main text is using a Bertolt Brecht [1898-1956] poem To Those Who Come after Us, and it’s this humane look on how insensitive we can be sometimes. And not to be too much of a moral judge on that, but that is what the body of the text is discussing. It’s really upsetting to now be where we are and looking back on that.

BL: I’m curious now to talk about “real time audio” generated in these 3D worlds. It’s not only an image, it’s also sound that’s spatialized and very much alive. As an artist, how important is sound to these works?

RR: Well, it depends. For “Stalking the Trace” and for “The Sky Is a Gap,” which is the VR piece inside “Stalking the Trace,” the sound is quite important because the delivery of whether or not you’re in control of that space has to be tied to your body. You have to actually feel it. When you move too fast or too forward, you can hear it in the audio. It’s instant, even if you move your head forwards and back, you can start to just feel the material of how fast you’re starting to move things around you. Everything is spatialized.

There’s one part where the scene is a simulation of one of the houses where I grew up in Florida. It’s this house on stilts, and this house is being blown apart. As you’re moving forwards and backwards, there are pieces of the house that are moving by your head, which you can hear based on how fast you’re moving, as the sound of it is blowing apart. It’s all 3D, as if you’re standing in that space.

There are other things that are as if you were standing where I was standing, making the piece. That stuff isn’t spatialized. There’s a part of the soundtrack where you’re moving it forwards and backwards, but it’s everywhere, it’s a universal sound. This is the same, for most virtual reality pieces. You have the soundscape for the entire work, and then you have things that are pockets that are spatialized. So, it just depends on what the piece is calling for.

BL: This brings us to the present moment, and I know you’ve been working in the studio. I’m sure you’ve been working hard, and I know it’s not an easy time to be working with the coronavirus. I have a couple of thoughts, but first I want to know what are your new challenges?

RR: As an artist, I feel like I’m unusually equipped for a lot of alone time. A month and this was fine. But now where we are today, I’m starting to realize how important it is to have a community, and I’m really missing that today. Social isolation does have consequences. I am forgetting how to socialize.

BL: Now, galleries and museums are mining their archives, putting all kinds of material up online. And they’re hosting conferences and lectures using zoom and other programs. We had also talked about AR, augmented reality earlier.

I have a show “Seeing Sound” that I’ve been working on with Independent Curators International (ICI) that will go on tour within the year. I know that when museums reopen, the issue of interactive work and the public touching gear is going to be really complicated. That brings me to VR headsets. Are they going to be disposable?

RR: I don’t think it would be safe to use a VR headset. Will they be disposable? Maybe. Between uses, there’s already a lot of sanitation. There’s a cover you can put on that’s disposable. The ins and outs of how to make that safe in a time where there’s an active pandemic seems quite difficult. My most recent VR piece is one the Akron Art Museum commissioned, and the VR piece is touring for the next year.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

I think it’s next stop is the San Jose Museum of Art. Skinsuits is a VR artwork that places participants wearing the headset into an abstract landscape, where the main action of the participant’s avatar is to continually shed its skin, revealing a new layer of character skins. Avatars as potential alter-egos make the VR experience feel somewhat diagnostic, as though in revealing a particular set of skins, the work tells participants something about themselves. We haven’t discussed what we’re going to do about that.

Or VR will start to move off of people’s bodies and back onto screens that are interactive, because right now the devices are so close to our bodies. The screens are inches from our eyes, and then with us sharing that space… it’s a little dangerous and moving too fast. Slowing the progress of this down is a good thing.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

I think the slower VR evolves the better. Our devices are so close to our bodies already as peripherals. It’s like they’re just peripherals for our cognition now. They’re moving into our psychological space, and the further that they stay away from our bodies the better. Of course, I work in VR as a medium, but I think that the slower that can move the better. The challenges that come with using VR in the future will slow it down. Unless everything just becomes mobile and you just give away headsets to people in the exhibition, which makes a lot of sense already. I find it unpleasant to share a headset with a bunch of people already. In a pandemic, it’s not a great idea.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

BL: I wonder if VR will then be part of people’s homes, where everybody will have their own headsets.

RR: I work in new media and I’m burnt out on screens already, because now my entire social life is here. So much of my emotional life, my cognition, my memory, the way I navigate cities is already offloaded onto a screen—which I’m grateful for, of course. But now that a lot of my social life is there, too, I’ve been wanting to spend more time with painting and less time developing and less time coding. Which is interesting—I would like to know other artists who work between the spaces, how they’re feeling. Really, all of my emotional life, including my social life, is lived virtually now.

There’s one thing, though, that is lovely about virtual reality, and does soothe some of the effects of this. And that is being able to have the facsimile of a body. That’s been really nice to be able to socialize with people and have even just a remnant of that. It’s a little sad, too, because you don’t get to really have that in real life, and it reminds you of that, so it aches a little bit to use VR chat.

My piece called Skinsuits is about moving through that. It’s something called the Proteus effect, about the way the avatar representations of ourselves affect our psychology. This is just an observable phenomenon: The bodies that we choose to inhabit bounce back into our personalities. In the words of my mother this morning, she was like, “Oh God, I’m going to be so much different after this.”

I had been in social isolation for a month and had my first physical conversation, so I actually forgot how much information was in body language. I had forgotten physically what it was like to see someone’s hand gestures fully in front of me. It was like, “Oh, okay. Yes, we are going to be psychologically different.” This is absolutely too long of an amount of time for it to not impact the rest of our lives.

I’m getting asked to do a lot of these virtual shows, and it’s just the last thing I feel like doing right now. I think that will change, as it sort of becomes a necessity, but I just want to be making paintings right now, and staying in the space of the body is just a way of soothing the effects of this thing. It’s the first time in my practice that I’ve said that. Painting and working virtually are usually pretty balanced—I go from one to the other, and they inform each other, and they still do. Of course, I’m still using maquettes, I’m still using the virtual spaces from the paintings. But I feel this sort of itchiness that I didn’t before. It would be interesting to hear if other people feel that way, too.

BL: Our world is changing so much, as we’ve been discussing. In general, I don’t like definitions because definitions are just handles that are very useful for a moment. When I think about your practice, would you consider yourself a “media artist”?

RR: Yeah, I feel the same way. I just feel like when you think about what “new media” is, of course that’s talking about the novelty aspects of technology—which I’m just absolutely not interested in. And “technology” ends up being a synecdoche for “novelty.” The reason I want to make virtual reality is because of what I can do in it, not the novelty of it. The categories end up being these category mistakes, in a way. My whole practice feels much more like the way multimedia or mixed media artists approach their work. I don’t feel like a “new media artist” so much, but I do work in new media.

BL: I hate that term, too.

RR: Me too.

BL: Early in my career I knew Bill Viola—Bill hated to be called a “video artist.” Hated it. It was like he wanted to be called an artist.

RR: Yes, exactly. Breaking it down by media—I mean, sure, if you’re just a painter, maybe it makes sense. But if you’re doing installation—especially someone like Bill—then you’re making art. You can call it experiential, you can call it whatever you want. But the categories are the least interesting part. So I’ll do it; I don’t want to, though.

BL: Well, thank you so much. You just shared so much great information and thoughts and ideas.

RR: Thank you, Barbara.

—

This conversation was recorded June 26, 2020; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Support for Barbara London Calling is generously provided by Bobbie Foshay and Independent Curators International in conjunction with their upcoming exhibition, “Seeing Sound,” curated by Barbara London.

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram @Barbara_London_Calling and check out BarbaraLondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Bower Blue , with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music.

Images & Video

Born 1987 in West Palm Beach, Florida, Rachel Rossin began painting at age eight, around the same time she taught herself to write computer code for MS-DOS. She received a B.F.A. from Florida State University, Tallahassee, and went on to combine her painting skills with VR technology. For research, she might hack action-adventure video games, like Grand Theft Auto or Call of Duty, to better understand how big-budget special effects are executed.

Rossin goes beyond the technical limitations of VR, especially the restraints of individual headsets that are geared towards the gaming world. Viewers of her immersive VR work dive deep into visceral experiences, either by putting on headsets, which enable them to turn with the sensation of moving 360 degrees in the virtual landscape, or by ambling with others through her installations surrounded by projections of stunning animations. She is also known to make witty aquarium-like sculpture with pristine, functioning computer parts that float, as if suspended midair.

Based in New York, today Rossin is motivated by a new challenge—real-time sound, audio that is generated within the 3-d world and is viscerally “alive.” Pursuing an independent path, she works mostly alone in her studio.

I Came and Went as Ghost Hand, first presented in the artist’s solo exhibition “Lossy” at Zieher Smith Gallery with related paintings, is a VR recreation of the artist’s home and studio, depicting objects that appear of that time along with items from her past. Upending traditional notions of portraiture, landscape, and still life, the images in the virtual world of Rossin’s painting studio both inform and reflect the technological installation. The artist inverts the most sacred of canons—venerable old school techniques with the sparkle of contemporaneity.

When viewers don a VR headset to experience The Sky Is a Gap, they enter a landscape and confront the exterior of a smoking Brutalist-style building. Moving in closer, they come face-to-face with the structure’s fiery destruction. When a blistering cloud becomes a haze of soaring debris, the moment moves between apocalypse and deliverance, much like the last scene of Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Zabriskie Point (1970). The viewer controls or “scrubs” time through their own movement within the piece, either speeding up the fiery denouement or traveling backwards, both spatially and sequentially. Each experience of the work is an intuitive response by the viewer. Wearing their own headsets, multiple, simultaneous viewers are able to sense each other’s presence, viewing one another as ghosts in the landscape, creating an uncanny social experience.

Rossin’s pristine, Plexiglas aquarium-like sculpture contain disassembled but functioning augmented reality computers that float, suspended in a viscous liquid environment. The non-conductive oil cools and lubricates the hardware, preserving the machinery for an indefinite life within the closed ecosystem. Rossin’s work explores the disembodied consciousness of everyday life in digital space: the seductive fantasy of a body freed from the limitations of anatomy and physics, the potential for abuse or disfigurement, and the inevitability of entropic deterioration.

The sculptural works share their origins with Rossin’s virtual environments. With or without physicality, they draw upon her own experiences of escaping and augmenting subjectivity through a merger with technology.

Rossin created her molded Plexiglass sculpture by first making a UV print from one of her VR spaces. She used UV printing to embed pigment on a sheet of Plexiglass to make it feel like a stained-glass substrate. After the printed process, and after she painted on top of the surfaces, Rossin softened the Plexiglass sheet with a blowtorch and used her body to mold it so that it actually stands up on its own, an echo of her body’s trace.

Rachel Rossin: Stalking the Trace from operating systems on Vimeo

When Rossin started to work on Stalking the Trace, she imagined an installation on the scale of a football field. “I wanted one-to-one with space and time, only moving extremely fast when you’re running it at that speed. Unconsciously that must have been in there, that experience of wanting to activate Dan Flavin’s work.”

Produced by and premiered at the Zabludowicz Collection in London in 2019, the tempestuous installation features cars floating along flooded streets, forests twisting in severe winds, and mammoth fireballs surging forward, one unfurling out of another as if they were Russian nesting dolls. When making the work, Rossin was responding to that moment, which she saw as a chaotic time of great acceleration.

Stalking the Trace viewers are offered two levels of experience. Those standing in the gallery watch and listen to a virtual narrator deliver a text written by the artist, accompanied by a sound collage—a so-called tone poem that serves to illustrate the VR work. Dense projections cover the gallery walls. Viewers who wear one of four VR headsets are able to move about in both the virtual and the physical space. While walking and moving within the gallery, the headset wearers experience the visual sensation of moving temporarily forward and backward within the image, doing what the artist calls “scrubbing time.”