This is Barbara London Calling. Welcome to my podcast series about the wild world of media art. I’m calling media artists from around the world, many of whom I’ve worked with as an author and curator. Together we’re exploring what motivates and inspires these artists, and how they see the world as media artists working at the forefront of technology and creativity.

Today I’m calling Anri Sala, an internationally acclaimed artist from Tirana, Albania. Born in 1974, Anri studied in Paris before moving to Berlin in 2004. Anri eloquently orchestrates sound in space with a keen focus on the underlying politics of contemporary life. Incorporating what he calls a distrust of language, his multi-media installations investigate the role of language and memory in our social and political history. Anri, thank you for joining me.

ANRI SALA: Thank you, Barbara. Thank you for inviting me.

Transcript

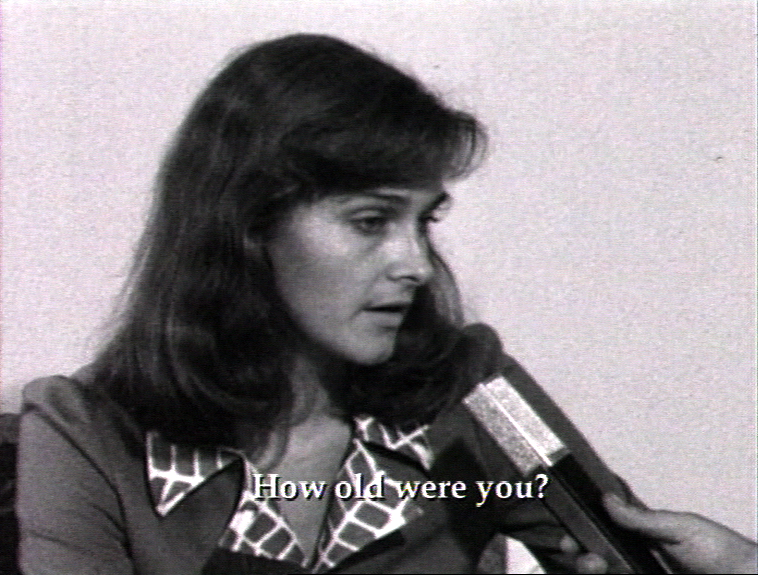

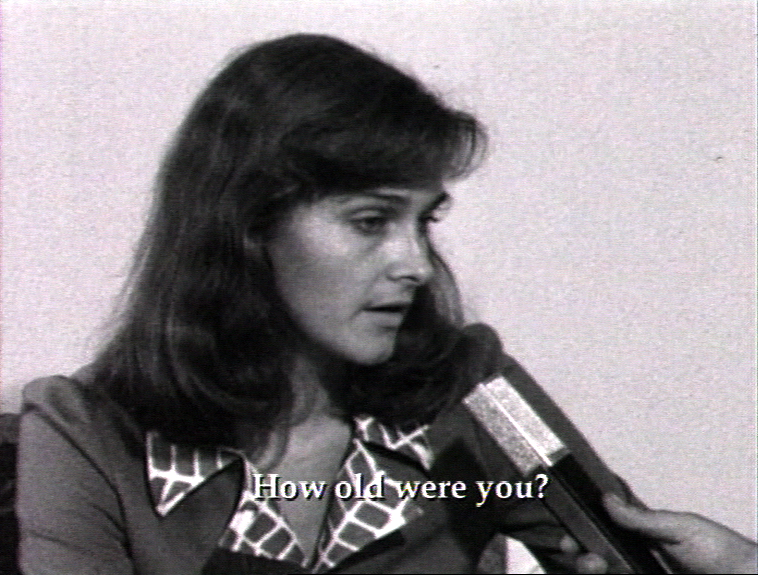

BL. You’ve accomplished so much during your productive career. It’s very difficult to figure out where to start. Let’s begin with your background. You received a BA in painting from Tirana National Academy of Arts in Albania. Then you did post-graduate studies in film directing in France. Your thesis project in 1998 was an accomplished video entitled Intervista: Finding the Words. A sort of detective story in which you reconstructed the soundtrack of a film that showed your mother talking about socialism and revolution. You said that making Intervista is what led you to distrust language. What did you mean by that?

AS. As you briefly so well explained, what triggered, what prompted Intervista and the making of it were two things. First, I had already moved to study in Paris; at the same time my sister left home. During one of the summer holidays, I was asked by my parents if I would go back home, as they were moving to a smaller house. They asked me to clean up my things and choose what I wanted them to keep for me. This is when I discovered this reel of 16-millimeter film. The film had no sound, something I discovered when I brought it with me back to Paris when the school year started again. This is what triggered what you call a detective story, searching first for the sound. In searching for the missing words, I realized sound was not part of the film. The second thing that made it possible is the fact that I had already moved to Paris, and I had this healthy distance from where I was coming from. This gave me the possibility to feel like engaging with the research and with the subject, the regime change. The move from dictatorship to a more open society, otherwise might sound heavy and too soon a subject to deal with, given the strong change and rupture that it produced in the society and in everybody’s life.

Single-channel video and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Ideal Audience International, Paris; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich

The artist carries out a kind of detective story, as he reconstructs the soundtrack of an old film that portrays his mother as a young woman talking about socialism and revolution. The work becomes a reflection on history and its traumas.

Now, to answer more precisely the question. In the process of making my film, when I couldn’t find the original sound of the recording, with the help of students and the people working in the school called the School for the Deaf and Mute Children in Albania, they read the lips of my mother. What is interesting is that by making this archeological act of finding what she had said by other means, by reading her lips, I discovered that the importance was not so much what she had said back then, because there was no surprise to it. It was an interview of the state. She was precisely answering the very same question that was asked to so many people back then. There is a very precise way of answering those questions. There was no enigma in that sense, although I believe it’s important to really walk the path of the things and find them for what they are, even if at the end one realizes it’s a copy-paste situation of everyone speaking with the same mouth and hearing with the same ears so to say.

However, the most interesting part was when, together with my mother, I showed her the subtitles, there was this moment that might come across as a moment of confrontation in the film, about her not agreeing to whether she said something that was very interesting for me. It’s not that she disagreed with the content of what she said because, like I said, we all knew what people could possibly say back then, what was the correct path of answer. But she disagreed with the lack of articulation that seemed to have been in the language. Looking back at it, not only now but soon afterwards, I think it was also that the language had changed at the moment of the rupture. Somehow, we were not within that language but we were suddenly objective about it. We could look at it from outside, and the syntax had broken. Meaning the syntax, which was meant to control how people spoke and therefore how they thought before they spoke was not necessary anymore. It had not survived this moment of transition in a malleable way, in an elastic way that had broken. This is what also somehow explains her hesitation to recognize that she spoke like that.

All this is what I mean that it’s a film that made me very aware and somehow distrustful towards language, that it made visible its opacity. Often language comes across as something which is transparent, especially the syntax, the grammar part of it. This is where you see that, in this case, at the moment that was controlling the language in the way it was put in sentences, what is called the syntax, and in this case had broken. It has become like a window where the glass breaks. This is where it becomes opaque. This is the first moment that made me very aware of the capacity of language and how, through syntax, there is so much control put upon the people. It’s done in a way which, as long as things are within their historical continuity when there is no rupture, as long as the glass is not broken, you don’t think of the glass, you think of the view.

BL. Around that same time, it was maybe a year later, you were moving along with your work. I’m curious about your video Nocturnes from 1999. Your video features two men, each revealing something about his life. One man has a large collection of fish, the other is a mercenary. They both talked to you and revealed their preoccupations. The work made me think about your own truth seeking and your very sympathetic eye to that of the virtuoso film essayist Chris Marker. Am I wrong in picking up a connection here?

Single-channel video transferred from super 16 mm film and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich

The video features two men, each revealing something about his life. One man has a large collection of fish; the other is a mercenary. They both make known their preoccupations. Sala’s truth-seeking, sympathetic eye may be compared to that of virtuoso essayist Chris Marker.

AS. Upon arriving in France, I was more and more aware and knowledgeable about French cinema, and film essays, which bring us to Chris Marker. There must have been, indirectly, a lot of that imbued in my interest in how to construct the story and how to let other people speak, and yet be able to escape from this documentary shell, which would have been too close to Intervista in that case. Finding that possible interval between fiction and documentary and real. In that sense, the poetry that comes from within the ambiguity of what is a fiction and what is not, takes, I guess, from that. But on the other side, this I can only tell because of having seen where my work has evolved, is that for me, not as much the truth because truth is such an evading notion, but the idea that the real of reality is important. In that sense, this is where it takes off from the film essay, where what is important is to be able to translate a pure thought into images.

My sensibility, this is where it goes in another direction, is that I’m not interested in having a pure thought, which after would manifest itself and communicate itself to an audience or to a visitor through images. But I want the reality of the process to become the thinking itself. Not what I want to represent, which would have been otherwise what comes close to this idea of film essay. In that sense, my work since then has not been so close to this notion of film essay.

BL. Then in 2003, your beautiful work Time after Time shows a very old horse standing in the dark of night, very dangerously it seems, by the side of a busy highway. Maybe it’s wrong on my part but it was so visual that I thought a lot about Georges Seurat’s mysterious, luminous works on paper. I wonder if that was pretty farfetched on my part.

AS. Well, I think it’s a beautiful bridge and a beautiful link because there is something about it in the sense of the softness of the image and not knowing where the focus is, and the thickness of the represented image with it. I think, in a way, one could think of Time After Time in that way, and how things only exist because of where the focus of the camera goes. Which brings this thing, which is more sculptural or is closer to the idea of representing something rather than presenting it, because it’s thanks to the focus that the thing is being represented. This brings it closer to the idea of the drawings of Seurat.

Single-channel video and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Bick Productions

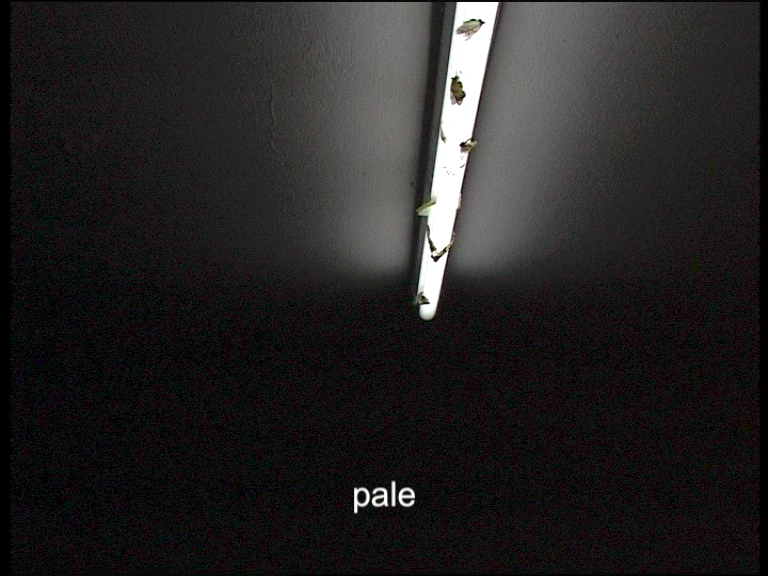

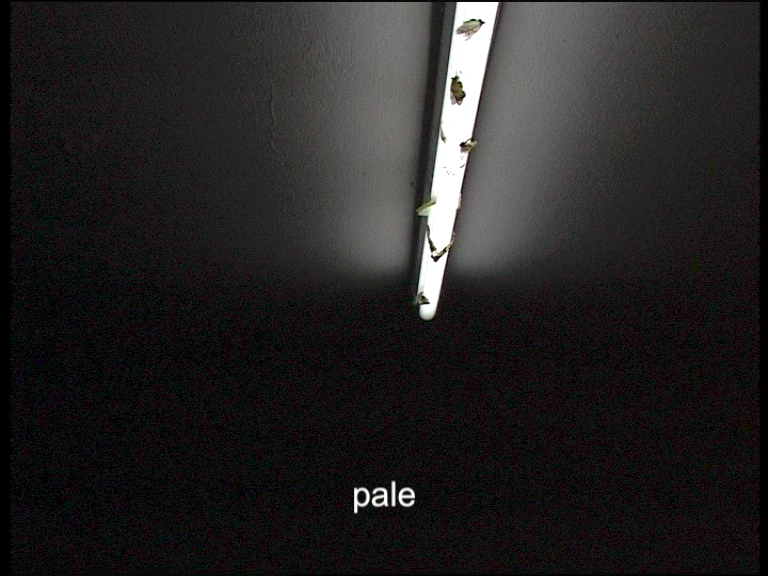

BL. Let’s move onto your later video Làk-kat, which I think is truly extraordinary, in the lush, luminous darkness of it. In this video from 2004, which is in MOMA’s collection, we see two very young boys seated together in a dimly lit room, and in their native language, which is the Senegalese language of Wolof, they practice over and over and over the pronunciation of words that all have to do with light and dark, including some words about race. Then you take the camera up to the moths and butterflies hovering on the florescent light on the ceiling. I’m curious why that move upwards for the viewer’s gaze and what brought you to Senegal in the first place?

AS. I was invited by a French Senegalese association that invited artists mostly from France but also from other countries, francophone or part of what used to be colonies of France. Actually, it was a very generous invitation because it was about spending some time there, and eventually something could come out of it but nothing had to come out of it, which is always a very generous invitation. We were in this town in Senegal, and in the day to day, the everyday life, I came across this notion in the Wolof language, which is one of the many local languages yet is the most spoken one in Senegal. It’s a language that is so extremely rich, and yet it does not have words for the primary colors such as blue, red, yellow. They’re all in French. However, it is extremely rich in being able to convey all the differences between white and black and brightness and sharpness and darkness. Also extending to the notion of skin and therefore background, belonging, identity, differentiation.

Single-channel video and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and and Hauser & Wirth; Marian Goodman Gallery; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

Seated together in a dimly lit room, two young boys repeat in their native language, which is the Senegalese language of Wolof, the pronunciation of words that all have to do with light and dark, including some words about race. Then the view abruptly shifts to butterflies and moths hovering on a fluorescent light on the ceiling.

Being there in a small town, being in a setting which was extremely intimate, speaking with someone meant one could really meet the other person. I was able to meet these kids and their mother. There was one radio station in that place. I met the person who was doing the programming for the radio, where this neon light is. It’s a very simple station. I wanted to produce a situation where he was asking the children to repeat all those words that somehow are there to articulate the many shades between light and dark and brightness, and the white and black and all the extremely important differences within. Within those differences, it’s not only naming whether it’s skin or a condition of light, but there also are different ways to name it. There is a respectful and a disrespectful way. Then there is also a way which is disrespectful, if I said it, but would be okay when said among themselves. All these little gaps, which can become unbridgeable when the wrong person says it to the wrong person. Also, about the positivity of language and how language records. Why Wolof had given up on the primary colors and so possessively kept for itself, within its own terms and words, all these differences between the different shades from white to black.

I must add that was the first part of the project when I did it, this being in 2004. Then I’ve been using this film as a tool; I’ve been expanding it in other different versions. Because I realized when I was translating it into English, I realized when I translated it into American English, one had to find other words to say it in the British English. Also, because, of course, you are dealing with what we just described is the relation to the other, the relation to skin color, the relation to the very history of each of these countries towards the others elsewhere or within the country. In the history of colonization, in terms of the United Kingdom but also the relation to what has been perceived for so long as ‘the other’ within United States. Words you could say in British English, such as “whitey,” which would be a derogative term in American English. Which does not fully translate the meaning of “Toubab” coming from Wolof. In the case of American English, which might be to say “the great, white hope,” for example, is more closely related to the history of the United States and its own very problematic relationship to that.

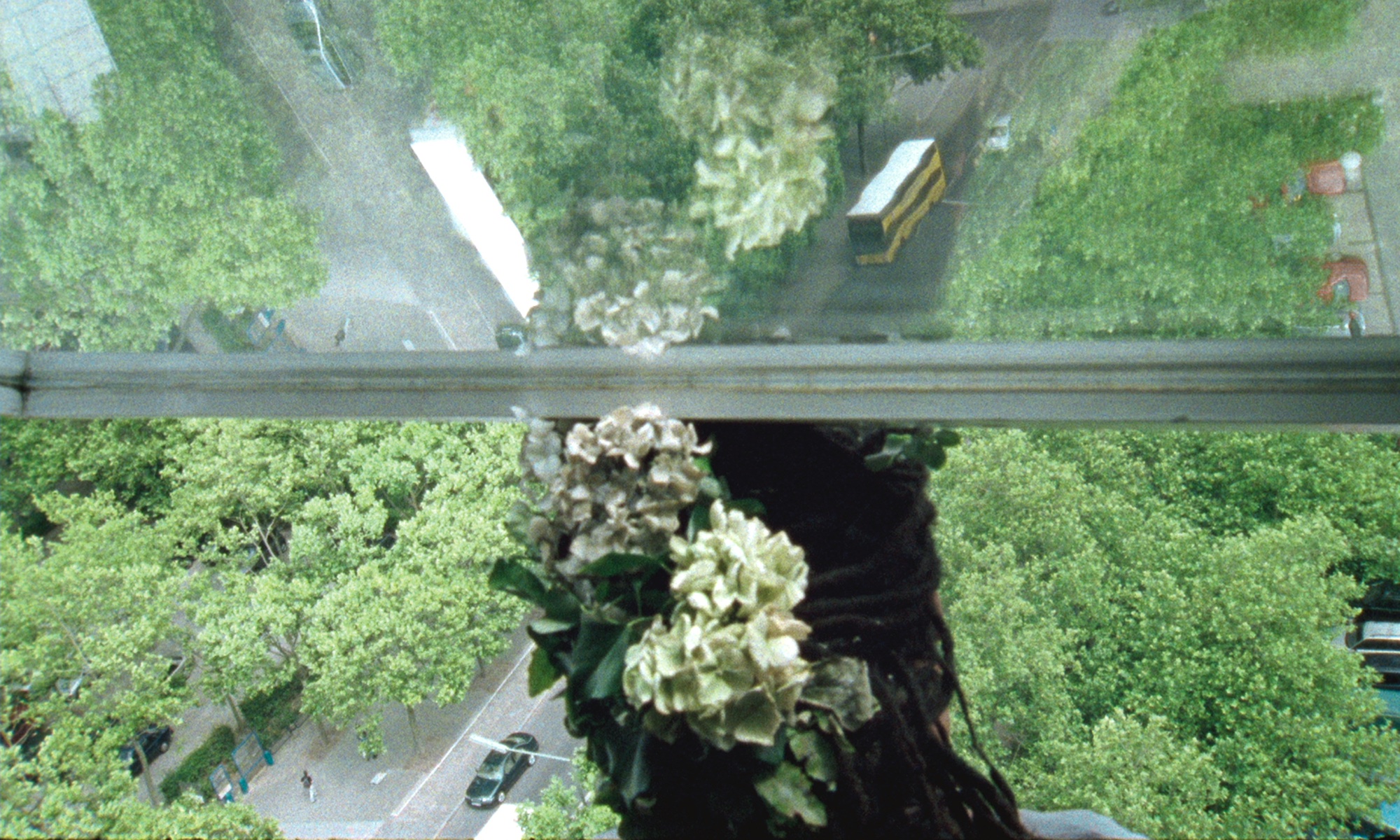

BL. Let’s move on to a very different work from Làk-kat, and that’s your work The Long Sorrow, which is an extraordinarily long take that reveals the interior of an upper story apartment in a modernist building in Berlin. It’s very bizarre but somehow it seems very normal. We see a window and just outside of this is a saxophone player incongruously improvising a wild rhapsody as he hangs suspended about 60 meters off the ground, dangling in front of the window. You’ve been in Berlin since 2004. I’m curious what were you capturing then and what is there to capture now?

AS. I think between then and now Berlin has changed in so many ways. There are so many of these ways that I myself cannot follow, also because at some point, as a city grows, we also grow and sometimes we grow together and sometimes we grow apart. Also, one should consider the fact of how much traveling happens, and of the curiosity about elsewhere and other places. I wouldn’t say that I’ve been a very careful follower of how Berlin has changed, although I live here, so to some extent I am a de facto part of it. But I think what I found in Berlin back then, which was something that I realized I was missing without knowing what it had to offer, very differently from Paris where I had lived just before. These places, which are not yet complete, these urban spaces of in between that could still double up one way or the other, well most of them double up the one way, the expected way, in terms of real estate that has opened, et cetera. But it was a time back then where a lot of things were happening, as if urban space was a sentence. I think back then it was still the sentence ending with a question mark. Right now, it’s ending with a full stop, because now it’s clearer what the urban space has become in Berlin.

Installation with single-channel HD video transferred from super 16 mm film and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery; Hauser & Wirth; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich

A long, slow “take” reveals the interior of an apartment in a modernist building in Berlin. Dangling outside the window and sixty meters above ground, a saxophone player incongruously improvises an exuberant rhapsody.

To go back to the Long Sorrow, I somehow felt at home with parts of Berlin. This related to growing up in Albania, even if the very place, the very location of Long Sorrow belonged to West Berlin; and why many people think it looks like East Berlin because of the modern looks of those buildings. However, it was part of West Berlin. I was very interested in all the ideas that propel this sort of building back then, which had to do with new achievements in terms of building technology. But also, they were thought of in a way that would make the relation between the private and the public more permeable. To some extent successful, and to many other extents it was a failure, which possibly also was because, I think, Germany, given the history and what it was coming out of, people were just getting back their privacy in a way. They were not ready to let it go in that sense. However, there’s been extremely interesting and successful architecture projects in terms of doubling up urban space and relations within that.

Long Sorrow was shot in the top floor, which actually was much higher. I would say somewhere between 60 and 70 meters high. It’s the 18th floor of this very long building called in German, Lange Jammer, which would be translated to Long Sorrow or a Long Shout. I invited Jemeel Moondoc, the Chicago born, New York based saxophone player, to come, and through his own means and the means of free jazz to make the building even longer. Imagining that the music would make the roughly 2,000 meters long building even longer both horizontally but also vertically. This is what it is, the setting. It’s how to extend the building by the means of music. What was also very important was the relation to free jazz, profoundly speaking free jazz, not free jazz as a style but as a condition. Being suspended in the void, high up outside the 18th floor, the only way for him to survive suspended at this height, to survive this precarious condition as much as it was extremely safe, of course, was to be totally immersed in the next moment.

In free jazz, not being scored, he was constantly venting what comes next, which would not necessarily be the same thing if it would have been a scored piece of music written for an instrument that like a violin and another instrument that is rather more connected to written music rather than improvised. I think intuitively I was bringing together different interests, and both on one side going toward something unknown to me, which was yet at that point, definitely I knew of it, as interesting to me. I like free jazz, but it was not something which was familiar to me. Yet transforming this setting and the questions around say public building, private versus public and transforming it into something I felt very familiar with, possibly because of where I came from and how I started to grow in this world in the very beginning, before the political changes.

BL. It’s fascinating how music plays such an important role in your work, and how/the way you kind of take it apart. But yet you’re very respectful of it. I was very moved when I saw your tour de force Ravel Ravel Unravel, which premiered in the French Pavilion but in fact occupied the German Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennial. I love your title and how it’s a word play on the composer Maurice Ravel and words ravel and unravel, which you did in a central space of the pavilion. Essentially, you transformed one space into an anechoic, non-echoing room, where one could hear and see two interpretations of Ravel’s Piano Concerto for The Left Hand in D Major projected simultaneously alongside each other. The two performances were executed by two great musicians, while in the adjacent room an amazing DJ, DJ Chloe, was filmed trying to reduce the musical echoes prompted by the two distinct executions. That’s a mouthful on my part… So why don’t we dive into this beautiful work and maybe you could tell me more about the dynamics of repetition and reverberation in this piece of yours and in your work in general.

AS. First, I was interested in developing a work around the notion of music written for the left hand, which makes you immediately think of something lacking, something missing, of a severed body, of an amputated body. Also, the left-hand repertoire, although it was born much earlier on, for other reasons such as personal accidents of a musician, but it became much richer in the course of or just in the aftermath of the first World War. This is also a moment when, like you said, music became increasingly important in my work. I think it also became important because you cannot just do anything with music. You have to have a tour de force with the music, and yet we have to approach it in ways that the music would agree, that it would bend itself to. On the other side, it’s this whole historical background of it, which I was not necessarily interested to represent, which maybe I would have done in the earlier work. Which is that it is more explicit in its relations to history and the relation between the history, the destiny of the people, the traumatic effect it could have on people’s lives.

Installations in two separate spaces.

Ravel Ravel, two-channel HD video and 16-channel sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Marian Goodman Gallery; Hauser & Wirth

But via the music, this subject is still about the same traumatic effect, what it means for a left hand to make up for the missing hand, which is the right one; and knowing that the piano as an instrument, that its own architecture is built around the right hand. How a left hand is able to play against, not only make up for the missing right hand but also to keep balance and to stand its ground against, say the 160 hands of the whole orchestra playing along because you are speaking in this case of a concerto, which is for piano and orchestra. I was interested in that, but I was interested in the interval, the in between and the echoes that it can generate. In this case, it’s more like musical echoes because it’s not based on the principle of space, like sound ricocheting or bouncing off a wall. But the interpretation of one pianist becomes, to our ears, an echo for what we just heard. Then there is this whole back and forth relation between one pianist being faster than the other, and then the other one catches up.

This interval between the two, it constantly evolves and it’s been constantly negotiated. Because this was a truth to show this work and to transform the space for it into an anechoic room, which both interests me as a metaphor, the idea of transforming a place, which is the main space of the German Pavilion. It by the way has an echo, which is equal to one of a cathedral, but also that it has so much repercussions in terms of history, to transform it in a place where we would draw all the possibility of acoustic repercussion. That was the main idea behind the use of the pavilion and how to respond to the opportunity to show in that pavilion, which was the German Pavilion, although I was representing France. The development of this idea of the interval and how I think it’s always within the intervals that history gives us a chance to repair ourselves in all the levels, psychologically, physiologically. This is why the moment of building this musical interval between the two executions was at the core of my project.

Secondspace: 4.0 surround soundPhoto: Courtesy the artist and Galerie ChantalCrousel, Paris; Marian Goodman Gallery; Hauser & Wirth; kurimanzutto,Mexico City

Then on the other side, I worked with this fantastic, extremely open minded, extremely talented and skillful DJ, DJ Chloe, who I asked to do precisely the opposite of what a DJ is supposed to do. Instead of producing a conflict or a syncopation, I asked her to reduce the two executions, to bring them back to sync. To somehow appease that situation and bring it back as much as possible to the piece that Ravel originally intended, which would be one pianist and one orchestra, instead of two pianists and two orchestras. Which is also humane, but it’s also almost an impossible task. I was interested not so much in the task succeeding or failing, but in the continuous effort and this negotiation between failure and success.

BL. Ravel Ravel Unravel is enormous and took you, I can only imagine, a good two years to create. Now moving on, your installations that feature drums, the first one I think was Moth in B-Flat in 2015 and then you’ve got Bridges in the Doldrums, 2016 and the Last Resort, 2017. All three feature drums upside down, suspended from the ceiling. They are worked with an interior so that the drum batons move to your specifications. The way they move, it makes me feel that they’re like bats, dangling from the roof of a cave. What were you aiming for in this quite disorienting and miraculous setup?

AS. Well, I’m interested in the suspended drums becoming like choreographic speakers, meaning they are not playing back or giving sound but are using sound, whether we hear it or not, to produce this choreography of the drumsticks. Then it brings us to this level of defying gravity, because the drumsticks are able to play their part although the whole drum is turned upside down. There is a little link to the idea of the moths, the idea of the moths and butterflies that come from Làk-kat, for example, which is where they do a first appearance. I’m actually more interested in moths than the butterflies because it’s a species that do not live well with daylight. During the day they try to find a shadowy corner, but they are very attracted to light in conditions of darkness, which is what makes them attracted to a neon light for example. I’m interested in this dichotomy between when light is not part of what is given, but it’s a moment for a recourse from darkness.

To go back to the drums, actually some of the drum works date from earlier. They have doubled up through stages, and I would say the most complete in terms of size and articulation of what they play is The Last Resort, which you mentioned. It is a work that was commissioned, and I presented for the first time at the Biennial in Sydney, Australia. It was a large-scale work made of 38 drums, which actually does represent a full orchestra of the modern times. In a way, when you are under the drums, you can comprehend that you are under a suspended orchestra. You can hear where the strings are, and you can hear where the other instruments are, the different parts of an orchestra. But I was very interested in the alteration of a concerto. In this case, it was the second movement of the Basset Clarinet Concerto of Mozart, which he composed, more or less, at the same time as the arrival of the first fleet in Sydney. It is also one of my main reasons for choosing that particular piece. I’m interested in its relation to the unresolved tension between the high ideas of enlightenment.

42-channel sound installation including 38 altered snare drums, loudspeaker parts, snare stands, drumsticks, soundtrack and 4 speakers Photo: Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery; Esther Schipper, Berlin

It’s a piece that corresponds to the Golden Era of Enlightenment. It’s one of the masterpieces of Mozart, who is one of the key artists of the time. How this high idea of “enlightenment” somehow got corrupted along the way, when people made it to distant shores; they rather translated it into loss and devastation more than emancipation. I was interested in how, through musical ways, not by just using music to tell an idea, but in musical ways, in ways that only music can accept. That is to alter the music, to corrupt the music in the same way that a lot of wood that drifts in the water and eventually makes it somewhere else, is corrupted by the elements of nature. The whole movement, the adagio of Mozart’s concerto was rewritten, but not so much the music. It’s the same in that sense as the Ravel Ravel project, where I did not touch a note of Ravel but only played with the distance between the notes. Meaning with the rhythmical arrangement…

In a similar way with this piece of Mozart, what the drums are playing is a new arrangement or new interpretation of the second movement, where I kept all the notes as they were written by Mozart. But the tempo indication was taken away and they were replaced by the wind indications that I found in an old book written by someone around the same time. It was the only book that still exists from the time. It was the diary of someone who traveled from England to Australia to start a new life. Because people traveled by boat back then, wind was an extremely important element; life and death depended on wind. In the daily entries of the man’s diary, the first sentence was always about wind. I collected all of these sentences about wind and translated them into tempo indications, which took over the original tempo indications of Mozart. It’s no longer the intention of the artist that is moving the concerto forward, but it’s more the wind conditions that are moving it forwards, from the first note to the last one.

BL. I happened to see the Last Resort at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York. It was quite spectacular, with the 38 drums suspended from the ceiling in this magical constellation. It was kind of a gravity defying ensemble that presents an unusual way to experience a contemporary interpretation of a Mozart concerto.

AS. One of the strongest images I have of Sydney is the bay, which is where the first fleet arrived in what became Australia. And this bay is one of the first things that you’d see. I remember the first time I went to Sydney some ten years ago, I saw a botanical garden, which is not far from the rotunda, the music pavilion where we installed the piece in Sydney overlooking the bay. It’s also where I saw these huge bats that were suspended on these huge, big, beautiful trees. I was interested not only because of the visual impact that they had, once you see them, but also the fact that they are not indigenous. They are not native species to Australia. I was interested in bringing together these different elements of something that does not belong to there, and is one of the strongest things you remember after having visited the bay. Also, by suspending the drums, it gave a possibility for people to be underneath, meaning not to look at the sculpture from around you but from under it. You can walk and sit and stand under this orchestra of drums. You can also recognize the geography of an orchestra, as I mentioned before. You can recognize where the wind instruments are and where the strings are, where the percussion is, and so on.

BL. Let’s move on to two other works. I’ve traveled a lot to Japan, particularly in the west. I was very interested in your 2017 installation, All of a Tremble. On the island of Teshima, you converted an old, abandoned house and you joined the sounds played by a music box on the wall with sounds of a shakuhachi, a Japanese flute, being played in a nearby projected video. What was your vision for this project and then, more broadly, what is it like working, sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly, between so many different cultures around the world?

AS. In this traditional house, I thought of a way of bringing different elements together and then be part of one score, like chamber music. Like different words belonging to different voices that can play sometimes together or listen to each other, making space for the other to be heard. All of a Tremble is one of the site-specific pieces that I’ve done. It actually includes an old European wallpaper roller, which was possibly used two hundred years ago to print wallpaper patterns. It corresponds to the beginning of the use of wallpaper and everything it means, in terms of the ideas about taste entered Japan from Western societies. Because it’s a concept that was not there before, then how it translates in a place where it’s not part of the history, in this case Japan, by going through the medium of syntax that is part of the place. So, I transformed this wallpaper roller into a music box, meaning the idea is that what would it be while part of the image of what is being played in sound now. The work triggered sounds of music box pins plucked by going against the musical roller, which is custom made for this piece.

Photo: courtesy: Benesse Art Site Naoshima. Photographer, Naoharu Obayashi.

This musical roller, when I produced it, was given musical value and scales which are typical to Asian or Japanese music. Non-Western musical scales. In that sense, you have a pattern which was a route or path of how taste and interior design and everything else that comes with it developed in a certain culture, which is Western culture, coming and being played by hitting or being translated into sounds by triggering notes which belong to a Japanese musical scale. Then there is the idea in my work the Long Sorrow, which we discussed before, but readapted, transformed into a longer sorrow with the addition of other instruments that are playing alongside with it. In this case, there is not only a saxophone player who is playing alone or together with a character in the film, but also a shakuhachi player who is playing along. I conceived of it as an exhibition, as I said before, like chamber music where you have a quartet or sextet that are playing together and listening to each other.

I also want to say something about what’s always been in my way of being and thinking, because you mentioned the idea of sometimes quickly reacting to places. I believe that everyone has the right to deal with context, to deal with information. Meaning, from the very beginning, I have always been against the sense that because of where I come from, me or only those of us who come from where I come from are the owners of the subjects that are ours, whether historical or everyday subjects. I think in that sense, I feel like a traveler that crosses the landscape of all this context and sensibilities respectfully, hopefully, but yet not being burdened by the codes that are innate to all the contexts. I think intimacy can also be very intimidating, and this is what happens with codes.

I think one could also bring this into the level of one of the things that I’m most interested in, when I work with film and with video; it’s how to use these tools, this media, this technology in ways that I do not rely on existing codes of narratives. The way I work with music is a very good example, because music is mostly used in a very codified way in filmmaking and storytelling. In that sense, I’m a strong advocate of trying to find ways to counter the codes, to not get along with the codes. I think there’s something very colonizing about how codes colonize our senses. Also, sometimes too much information is another way. We all strive for information, but it’s also a way of conditioning our perception of things.

BL. That takes us right into another very beautiful and haunting work, one I also saw at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York called If and Only If from 2018. It’s very spare; it’s a two-channel video sound installation with a semi-transparent screen. A musician plays Stravinsky’s Elegy for Solo Viola, as a very exquisite snail very slowly and very meticulously crawls up this viola player’s bow. It’s curious that you turned a solo composition into a duet and a very unusual collaboration, because the snail is very much part of the performance. Could you tell me a little bit about the work and maybe how you work with or how you perceive the coexistence of man and nature?

Two-channel video-sound Installation

Photo: Courtesy the artist

AS. Well, I was interested in doing the shortest possible road movie. I had an idea more of an image which was the journey of a garden snail across the length of a bow, whether violin or viola and then thinking of what could be the piece of music that could go with it. After a lot of listening, I decided to use the Elegy of Stravinsky, which also comes not only with its own context, but also with its own syntax. Although it’s a solo work, as the title very well says, it’s constantly played on two strings. In a way, it’s a monologue that contains a conversation inside. I was interested in expanding this conversation in this collaboration to a continuous negotiation between the viola legend, Gérard Caussé, and the garden snail. In that sense it’s a very elastic performance. The music stretches itself to correspond to the time it takes the snail to reach the end of the bow. The goal was how to make a film that the duration of the film, the duration of the Elegy and the duration of the journey of the snail, which depended also on the length of the viola bow, when they came together to one conclusion. They were in sync together.

Then of course there is also, like you say, a kind of collaboration, because the violist has to take into account not only the pace of the snail but also where the snail is at any given moment, and how one wouldn’t think of it. The snail’s weight starts to count more, the further it goes toward the end of the bow. How it wants to protect its shell when it’s coming too close to the strings of the viola, which somehow makes the musician change his own choreography of action to make space for the snail to not crush against the strings. Also, take into account the space with the ultimate goal that the music becomes a soundtrack to the snail’s journey from the beginning to the very end of the bow. In that sense, the collaboration is between the musician, the human being, and the snail; it’s not even a metaphor in that case. It’s a real collaboration, because one has to take into account the other. It’s a big conditional situation. That’s why I also like calling it If and Only If because it’s also the mathematical name for conditional situations, which is also the beginning of the idea of algorithms.

BL. It’s a really precise work. Is it always presented in two channels?

AS. In the way you saw it exhibited at the Marian Goodman Galley in New York, it was a more sculptural display with the two screens. Also, because there are parts of the film, which I shot with two cameras, usually according to the protocol that you film to make a 3D image. But I was not interested in making a 3D film. That’s also the reason why I not only did not put the same lenses on both cameras but I also did not have the focus correspond between them. This is what produces these moments when the shot in the back becomes wider, and the focus goes from one screen to another. But also, the installation exists as a single channel work. I like not just working on new ideas, but also use existing works to rethink the relation between these works or between them and themselves.

If and Only If also finds itself as part of other work in Santander, Spain at Centro Botín. The exhibition is called “AS YOU GO,” and If and Only If is shown together with other works in a completely different way than how you saw it at the gallery in New York.

BL. Tell me more about “AS YOU GO,” the exhibition at Botín in Santander.

AS. I had to rethink, again, the way how things evolve in the exhibition, yet the concept is the same. How to make an exhibition where the works are moving image, and the exhibition becomes like a parade. The works, like the visitors, stroll through the spaces. They are not static; they do not own a room or own a space like the projection normally would; rather, they go around. The different works, they exist in multiple instances, in multiple places at once. Then the wish is also to invite people to either walk along with the exhibition’s pace or they could, as well, lay down and then the exhibition would just pass in front of their eyes, or they could also go against the flow. It also deals with these notions of how we experience time and, to go back to language, how thanks to language as well, we experience time as past, present and future, in ways that language is also syntactically organized. Then it’s more about producing a continuous present, but we’re still this, if you walk faster than the exhibition, you’ll catch up with it again. Then you have the feeling that you have walked faster, you have gone towards the future of the exhibition. There you are caught up with something you believe you have seen before.

I’m very interested in thinking or anticipating what could be the possible movement of the people in the exhibition. That adds another dimension to the relation between the visitors and the work. If I would bring this whole experience of how it is when people have to continuously walk, if they want to be in a static situation with the works or if they stop then the exhibition walks for them. That would be a little bit like the film we just discussed, If and Only If, because there the exhibition would be like a bow and then you would be a little like the snail that covers the whole length of the exhibition. But just when you think that you have covered it all, the movement of the bow goes back and forth again. It becomes like a loop.

For me it’s very important that it’s not about having an ultimate goal about the exhibition, but it’s about building the trajectory. Building the experience of the trajectory and questioning. For me, a dimension of my work is also working with the idea of never knowing for sure where one should be in an exhibition. You are constantly searching for that right perspective. Actually, there is not a right or wrong perspective about it, and this produces a lot of subjectivity depending on where people are and what they see and how they see and what they hear, depending on the position where they find themselves. Based on the same concept, I hope the work is still able to translate in so many subjective encounters with the public.

BL. I think you’re a great artist for a museum curator to work with, especially now with COVID that we’re all forced to reevaluate and reconsider how to present an exhibition.

SL. Thank you, Barbara.

BL. My last question is one I ask everybody in this series. Do you consider yourself a media artist?

AS. Yes and no because media, the name, has grown so much. It does not necessarily mean what it was meant to mean before and I think as artists, we do not only work with but we also question the tools that we employ. In that sense, when I think of media, it has increasingly become a success story that has stopped having a critical approach to the tools that it uses. In that sense, I do not consider myself at all a media artist. But I consider myself as somebody who uses the same tools but at opposite ends.

BL. You’ve been very generous to spend so much time talking with me today. You’ve revealed so much about your work. I really appreciate it.

AS. Thank you. It was a pleasure, Barbara. Thank you.

This conversation was recorded on July 13, 2020 and has been edited for length and clarity.

Support for Barbara London Calling is generously provided by Bobbie Foshay and Independent Curators International, in conjunction with their upcoming exhibition, “Seeing Sound,” which I curated. Be sure to like and subscribe so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow up on Instagram @Barbara_London_Calling and check out BarbaraLondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed. Barbara London Calling is produced by Bower Blue with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music. Thanks again for joining us. We’ll see you next time.

Images, & Video

Observing the role of language and memory in social and political history, Anri Sala eloquently orchestrates sound and space in compelling multimedia installations.

Single-channel video and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Ideal Audience International, Paris; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich.

The artist carries out a kind of detective story, as he reconstructs the soundtrack of an old film that portrays his mother as a young woman talking about socialism and revolution. The work becomes a reflection on history and its traumas.

Single-channel video transferred from super 16 mm film and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich

The video features two men, each revealing something about his life. One man has a large collection of fish; the other is a mercenary. They both make known their preoccupations. Sala’s truth-seeking, sympathetic eye may be compared to that of virtuoso essayist Chris Marker.

Single-channel video and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Bick Productions

The video shows a very old horse standing in the dark of night, very dangerously it seems, by the side of a Tirana highway. Viewers may see an affinity to Georges Seurat’s mysterious and luminous works on paper.

Single-channel video and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and and Hauser & Wirth; Marian Goodman Gallery; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

Seated together in a dimly lit room, two young boys repeat in their native language, which is the Senegalese language of Wolof, the pronunciation of words that all have to do with light and dark, including some words about race. Then the view abruptly shifts to butterflies and moths hovering on a fluorescent light on the ceiling.

Installation with single-channel HD video transferred from super 16 mm film and stereo sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery; Hauser & Wirth; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich

A long, slow “take” reveals the interior of an apartment in a modernist building in Berlin. Dangling outside the window and sixty meters above ground, a saxophone player incongruously improvises an exuberant rhapsody.

Installations in two separate spaces.

Ravel Ravel, two-channel HD video and 16-channel sound Photo: Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Marian Goodman Gallery; Hauser & Wirth

Firstspace: stereo sound

Secondspace: 4.0 surround sound

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Marian Goodman Gallery; Hauser & Wirth; kurimanzutto,Mexico City

The titles are a wordplay on the name of composer Maurice Ravel, and the words ravel/unravel. The dual installations present two interpretations of Ravel’s “Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D-major,” projected simultaneously alongside each other in the central space. In an adjacent room, DJ Chloé is shown trying to reduce the musical echoes prompted by the two distinct executions of the concerto, and therefore is trying to bring the concerto back to itself.

The spare two-channel video sound installation with a semi-transparent screen revolves around a musician playing Stravinsky’s Elegy for Solo Viola. An exquisite snail slowly and quite miraculously crawls up his bow. A collaboration of sorts, the composition concludes when the snail reaches the top of the bow. Sala turned a solo composition into a duet and a very unusual collaboration, because the snail is very much part of the performance.

Photo: courtesy: Benesse Art Site Naoshima. Photographer, Naoharu Obayashi.

42-channel sound installation including 38 altered snare drums, loudspeaker parts, snare stands, drumsticks, soundtrack and 4 speakers Photo: Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery; Esther Schipper, Berlin

The gravity-defying ensemble of thirty-eight custom-built snare drums presents an unusual way to experience a contemporary interpretation of a Mozart Concerto. The musical dialogue animates the relationship between sound, place, time and history in this haunting work.

Two-channel video-sound Installation

Photo: Courtesy the artist

The spare two-channel video sound installation with a semi-transparent screen revolves around a musician playing Stravinsky’s Elegy for Solo Viola. An exquisite snail slowly and quite miraculously crawls up his bow. A collaboration of sorts, the composition concludes when the snail reaches the top of the bow. Sala turned a solo composition into a duet and a very unusual collaboration, because the snail is very much part of the performance.