[February 23, 2022 | Season 2, Ep. 9 | Barbara London Calling]

Barbara London: My guest today is Ed Atkins, an English artist whose lively practice revolves around writing, the moving image and installation, with a keen interest in the emotions our digital technologies are unable to contain. Born 1982, in an English village outside Oxford, Ed grew up in a household that considered literature to be the creative pinnacle. He graduated from London Slade School of Art in 2009. That same year, his father died of cancer. Death, loss, distemper and debility have been preoccupations ever since. Ed, thank you so much for joining me.

Ed Atkins: Pleasure. Thanks for having me, Barbara.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: I’m fortunate to have experienced a number of your solo shows, including one at MoMA PS1 in New York; in the Arsenale at the 2019 Venice Biennale; and your recent show at the New Museum.

Venice Biennial, 2019.

Courtesy the artist

Venice Biennial, 2019.

Courtesy the artist

But I want to go back and start earlier. I gather your interest in the moving image began at a young age. I’ve read about your fascination with the work of three very different artists: Werner Herzog and his epic film Aguirre: Wrath of God, 1972; the darkly surrealist Czech filmmaker Jan Švankmajer; and the structuralist filmmaker Hollis Frampton. Tell me a bit about your early influences and your fascination with the moving image.

EA: Sure. I mean, a lot of it is without choice. This was stuff that my father would be secreting into mine and my brother’s psyche, somehow. He’d be trying to school us, but it was also some dubious experiment, which I think is quite common for parents to kind of say: “Ooh, I wonder if they’ll like this.” But it would just be weirder stuff.

My burgeoning interest in cinema coincided with a moment in British TV when we had the first VCR and late-night programs, particularly on Channel 4. There were only four [U.K. TV] channels. On Channel 4, they were showing a lot of shorts, contemporary dance, animation, and very odd films.

My father was a big fan of Gothic horror stuff, but also European, more-or-less art house stuff. I do remember Aguirre: Wrath of God. I don’t know, but that really struck a chord. [Seeing the film] as a little boy, I think I was obsessed with a notion of conquistadors, but also with the film’s complete rejection of the usual Hollywood heroism, and also with this sort of weird psychic realism within the whole thing. It was very unplaceable.

You get this sort of exorbitant fantasy and fiction, which would be Klaus Kinski’s histrionics, mixed with this verité camera, which obviously I didn’t think of it in those terms at the time. But you think this is both phenomenal and terribly made, and sort of real.

I remember it really vividly. Švankmajer was a family favorite. We all loved Švankmajer. We’d recorded some off TV and would watch his shorts quite regularly.

But also his version of Alice in Wonderland was a key influence in the house and a massive influence on me. I’m still stealing from him, really. Or at least I’m trying to reach certain pinnacles of feeling that he manages by effect, particularly by his use of Foley [sound effects], which is always so excessive and clunky and wonderful.

But then also, again, the push and pull between the wildly unreal and reality. He would often stop-frame animate real things. Not just clay stuff, but skulls and bits of meat and taxidermied things. It’s a wild thing. It’s hugely influential stuff.

Then Hollis Frampton would be much later. That would be really just floundering at art college, I think. Like a lot of art students, it takes a while to get back to allowing yourself into those things you obsessed around when you were a child or when you were a teenager. You kind of feel like you have to get rid of childish things and certain ways. And then you allow them back in, potentially via more or less bonafide artists, artists who are actually attached to similar things that you’d already sensed.

So it’s a sort of a potted [preserved] little map of a certain time. There’s lots in between, but I think probably those are the things I list because they’re the things I feel sufficiently guilty about pilfering from or being really influenced by.

BL: You are a genius with the moving image and you’re very interested in the written word. I’m curious, what led you early on to what we could call the technological literature of Robert Coover, an American author who in the 1990s experimented with hypertext. Was that something that you were intrigued by?

EA: Yeah, I mean less his later stuff. I think again, to be so boring, it was stuff that was in the house. I was very lucky to have a father and a mother who read a lot, and quite widely and a bit weirdly. But I do remember, and I think there’s a sort of truism about a lot of that kind of more fun postmodern American stuff that felt so distant from a little village in England, and so exciting. It was doing stuff that not much British literature had done or was doing. It was a kind of affording of a more or less pop vernacular and free experiment of voice and of form, with complete abandon. And obviously the people were really extraordinary at it. I would probably put Donald Barthelme at the top of that [list], in some way, someone who wrote very serious and amazing literature at the same time as being really fun.

I think, for me, that was the first encounter with things that could be both high—in terms of being affirmed as literature or cinema or whatever—but that could also be silly and clearly fun or free. It forwarded a way through a poker-faced aspect that could thwart your ambitions if you encounter just the very serious end of certain things. I think my father knew this and therefore was, again, quite instrumental in feeding me more or less silly stuff. At the same time as the American post-mo [postmodern] stuff, I’d be reading At Swim-Two-Birds, the kind of [metafiction of] Flann O’Brien—Irish and very surreal, very funny, very odd stuff. Again, written in vernacular language. I don’t know, the stuff that you would read and think, “I could probably do that” in some way, I guess.

These are slightly benign answers, aren’t they? But I suppose, for better or worse, the things that one is excited by at a certain point, you can’t shift them. They’re just forever there. And however much you might remind yourself to not—because these things are also so tempting to be plagiarized in certain ways—the first thing you probably want to do when reading Donald Barthelme as a teenager is to write like that, to be this exorbitant stylist, which is obviously ludicrous. Of course, the first attempts at these things are ludicrous. Because actually, maybe, there’s a common ground with a lot of this stuff, a sort of collaging and a certain kind of relationship to an edit of reality and of the jump cut, a juxtaposition between them. It was the liberalness of that. You could do that, I suppose.

BL: That’s a nice segue into what is intriguing about your video work. Of course, you always do a lot of writing, but your video work revolves around avatars. These are characters that you’ve described as containers or empty shells. You’re able to do a lot of constructing, or putting in or dwelling in places that might be uncomfortable otherwise. Let’s use as an example your two-channel video animation Us Dead Talk Love from 2012 that ironically or oddly features two decapitated heads who interview each other about very physical things, such as their eyelashes, their hair follicles. All of these details refer to their absent bodies, their eyebrows, twitches, and stuff. They speak in a strange blank verse of the flesh and blood that they don’t have. Let’s talk about that. Also, I’m curious to know, was Julia Kristeva’s 2011 book, The Severed Head, an inspiration or not?

Video still. © Ed Atkins.

Courtesy of the artist, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Cabinet, London, and Gladstone Gallery.

EA: She was, but I hadn’t encountered that one yet. I have subsequently. Yeah, it’s funny, isn’t it? Because I think the thread maybe from those things that I found very formative to me was almost exclusively stylistic, to a certain extent. Because in a way, the substance or the quote unquote content, although I wouldn’t really necessarily delineate the two. It’s almost like using the surface and the sort of style, and almost the lustrousness of a certain kind of style or surface behind which you can wear a skin or a mask or whatever. I suppose, for a certain period I railed against a term like avatar, if only because of its ubiquity. But yes, you’re right. Using the computer-generated performance capture figures in that video was the first time of properly using something like that. It was off the shelf stuff, just a bit of software. I used the model that came with the software. There’s nothing special about my interference with it, except that I’m wearing it. And actually, that’s continued to be the case. It’s that a lot of the figures that are in the works are more or less off the shelf. So, in a way, there is this disjunct between the thing that you’re seeing, the slickness and the surface, and then, the thing that is behind it is constantly erupting through it. And then receding again, as a kind of constant relationship between a surface that is recognizably smooth and fluent in itself, but also in its cultural references and things like that; and then there is this kind of unruly thing that is wearing it in some way. Though I would use it as an analog for just being a person anyway, you know, I suppose? There is a psychological depth to them, which is deliberately at odds with the thinness of the surface.

Video still. © Ed Atkins.

Courtesy of the artist, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Cabinet, London, and Gladstone Gallery.

Video Still. © Ed Atkins.

Courtesy of the artist, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Cabinet, London, and Gladstone Gallery.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vM0hHSKfZw8

BL: That’s how I experienced your work, Happy Birthday from 2014. Obviously, a birthday is every mortal’s chronological marker. Whether we like it or not, the date is marked by friends or family as they sing that ridiculous happy birthday song. For the work you installed a standalone screen, with quite good speakers. The projection opens with a close up shot of the ocean. So, the viewer initially thinks, oh nature, how lovely. Then this character Dave comes out of the water. He’s a young man with the year 2016 tattooed on his forehead. He delivers a very sober monologue, in which he is marking, repeating arbitrary years and dates and things. I want to know about your choice of music, because along with the days of the week and time phrases, there are snippets of Willie Nelson’s very familiar song, Always on My Mind. How do you develop a work like Happy Birthday?

EA: I was talking to someone about doing a sort of conversation thing relatively recently. And we got to this point where we were talking about that maybe the videos aren’t constituted by imagery, to a certain extent. This is a little bit askance. I’m pulling it back, I promise. But just that what you’re looking at, you’re never really allowed to forget [that] it is a kind of digital construction, that it’s code, in certain ways. I mean, that’s a root via the overt artifice of the thing. There’s no index, right? There’s no “thing” that it’s a photograph of or a picture of. The oddness doesn’t exist anymore. The certain point, I suppose, what I mean to say is that the music, the so-called imagery, the sound to me, all of these things are more or less holistic. I don’t really treat them as different things.

The way that software exists is that most of the time you have to work within these parameters. But for me, they tend to occur at the same time. Or at least in the first instance, there’s a kind of maybe a refrain. Or I was recording myself reciting these numbers arbitrarily, wandering around an old cigarette museum in Ljubljana [Slovenia.]

I think I was on a residency and I had this kind of thing. But at the same time, I was obsessed with listening to various versions of You’re Always on My Mind, and obviously the constant thrum of certain familial relations and losses and things. I don’t know, these things congeal into a thing. I’ve said it before, but part of the usefulness of treating these videos as bodies, to a certain extent as dead men. as I’ve sort of toyed with before, is that it fights against any kind of version of dualism, where things are separated. There is the music, which would be the way that we would describe cinema, it’s moving parts of something. It would be like the image, the sound, and it would be an industrialized breaking down.

Whereas for me it’s best to think the experience is one that is all together. There is this total concert; an exciting moment really is of convening these things into something that then is a compound. You can no longer pull them apart. I feel that when it really works, the videos do that. They do a sort of impossible job… The spell pulls them together. I don’t know if I’m explaining that very well, but certainly the music is key. It’s also the thing just generally in our lives that we allow to not really have overt meaning in terms of one interpretative point or something. Even if it’s a song, we tend to personalize it or make it about ourselves or about something else. It’s attached to experience in a way that is somehow unlike a lot of other things.

And so, it does a lot, if I was to be demure. It would be the fact that music does a lot of the emotional heavy lifting in a way, as it always does. But at the same time, I don’t know. I mean, using a song as overly sentimental as You Are Always on My Mind, which is also wonderful. I love it. Also, it’s too much. There’s an excessiveness to it, a sentimentality rather than just sentiment. I would say that that kind of excessiveness is also happening throughout the whole work, in terms of the compression to say a ten-minute video of feelings, of too muchness. The kind of overwhelming movement, motility to the whole thing.

BL: As you’re talking, it’s a bit like the very physical way that Matisse worked with clay. You’re constructing something time-based in a very malleable, organic-feeling way. There were a couple of your earlier works where you really stretched out time in very long duration. One is eight hours, another is fourteen. You do have music in your eight-hour No-One Is More “Work” Than Me from 2014. You’ve got the avatar addressing the viewer, as blood’s trickling out of his nose. And then you incorporate Brian Adam’s song, Everything I Do (I Do It for You). I’m curious, why is the duration eight hours for that work?

Video still. © Ed Atkins. Courtesy of the artist, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Cabinet, London, and Gladstone Gallery.

EA: I think, if I’m honest, both of the longest animated things are the most overt failures for me. I don’t mean that badly. I like them, though I can’t make really much sense of them. I suppose, in their longevity, they start to ask whether they’re incredibly short, really. There is a certain wraparound of vastly long, versus, is this repetition and the tightness of the little loop of them. There’s something on a long enough timeline, et cetera. They become entropic, in certain ways, or you’ll never see them all. Or at least they nod towards that. Obviously, they’re not long enough to do that. Particularly, No-One Is More “Work” Than Me. I think there is an improvisatory aspect to that. That was me sitting in front of the software and the hardware and sort of just going for it. I don’t know. I mean, it was an attempt to maybe overly emphasize the performance aspect of the technologies that it is attempting to sufficiently document a person. And the other one, that performance capture with lots of different of people in it. I love that one because the experience of making it was so important, in terms of moving away from just me being the sole protagonist or not protagonist, but model or something, and much more violent because of it, because I’m making a lot of other people go through the same rendering process.

Again, I like that work because I don’t know what to do with it. It’s not an easily digestible thing. And I think there’s also…, if there is any latent ethical imperative to a lot of the work in terms of what it means to capture someone, to render them, et cetera. Then there is a point at which with performance capture, that very long work with lots of different people, that I shouldn’t to resolve it. To continue to work on it is to continue to overly perform the violence that’s already there.

It doesn’t need me to cut it to add more symbolic violence to it. It’s also become something else, becomes like a census or something. It’s like, there’s lots of different people in fragments reciting this text by me, which is sort of very nonsensical in certain ways, or at least purple.

BL: I think, well there have been other artists, such as Steve McQueen who made his work a work [Caribs’ Leap/Western Deep, (2002)] that was solidly durational. I think some of us are very used to long duration, and some of us are not. I remember being in Madrid at the Prado Museum and standing for several hours studying Goya’s painting The Third of May (1818), because it was so freaking dense. A video work of long duration, like what you were just describing, could be installed at a museum where viewers could drop in, drop out, have lunch, and come back. There’s always that.

EA: I mean with those things you always think, could it be on? You want it to really be allowed to be a sculpture. To be like the Christian Marclay’s twenty-four-hour Clock (2010). There’s a kind of demand to be just treated like a clock rather than like a cinema or something. And the same would be true here, is that it has to recede from the art object to a certain extent in order to be what it maybe really is. Like just a bit of bureaucracy, actually, in some future horror, you know; it’s this terrible form that people filled in or something.

BL: We’ll now go on to your very recent work. I went back a couple of times, after we had a coffee together. The title of the show is “Get Life/Love’s Work” (2021) and it premiered at the New Museum. I know you worked on it for a quite a while, as production of the video [The Worm] was delayed by COVID. It’s a gorgeous projection in high definition, a very convincing, quite visceral animation that portrays a man seated in a very handsomely appointed talk show kind of TV studio. The character is a stand in for you. The young man, you, smokes, sips from a glass tumbler, maybe whiskey, maybe not. He engages by telephone in a free-flowing conversation that we hear with his off-screen mother. It’s very interesting, as together you both discuss family history, a kind of genealogy. I want to add a couple of points that we can discuss. You chose to project the work as a rectangular 4:3 aspect ratio.

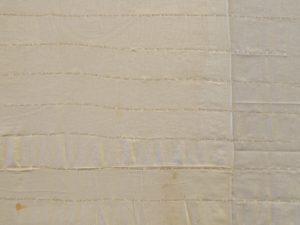

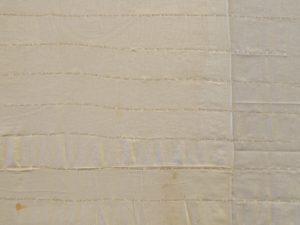

That format is early television, early video, not the current film ratio, 16:9. And your projection screen resembled a plush double mattress. Its surface was actually composed of stitched together, somewhat soiled old linen table cloths, with barely discernible text embroidered on the surface. It was fascinating to me, so I moved close and tried to read the text. Not everybody did this. The screen is attached to a 14-foot-high plywood wall.

Actually, the screen wall is part of an enormous plywood box that extends back 26 feet. Its interior is empty, and the visitor was free to enter. Because we’re museum goers and often are told no, no, no, you are not allowed to enter. But in your work, it was yes, yes, yes, walk in, and you feel that emptiness. You had other material on the peripheral walls. You had other stitched together, old linens with embroidered texts. You had pages of paper, covered with other texts. It’s a very spare, but very jam-packed show with a lot of ideas. I could go on…

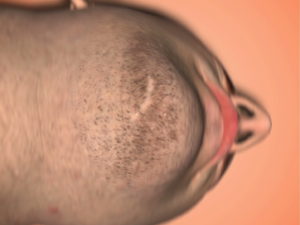

I’ll describe a little more. In the video, you actually were speaking long distance by phone with your mother, Rosemary, who was in England. You were in Berlin in a hotel room, working with an outstanding technical crew that you assembled through the support of Nokia’s Experiments in Arts and Technology program.

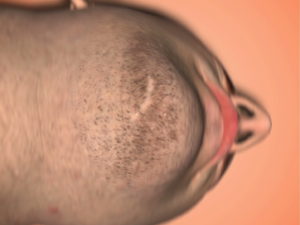

You had a GoPro camera on your head.

Image, courtesy the artist

Commissioned and produced by the New Museum and Nokia Bell Labs / Experiments in Art and Technologies

You had all of these sensors attached to your body, which we don’t know. These sensors captured your every move and twitch. Meanwhile, the crew is in the adjacent room operating the gear. This is a very, very complicated piece. It captured the virtual live view. It’s really you as an avatar. Do you want to explain, how do you expect the viewer to unpack? It’s such a dense work?

EA: I suppose I don’t really, not fully. I expect them to intuit a lot of it because I think it’s possible. I mean, obviously it’s not a real person, but obviously, I hope, or at least the suspicion is that the voices are real, that the movement is real, that there is some other… That there are at least a few different kinds of technologically mediated realities happening at the same time. I think depending on your generation, I suppose, or your familiarity, then you would recognize certain of the kinds of tech. But I think more than that, in as much as I’m not really interested in the tech, there’s no part of me that thinks about the future of tech. There is no abstracted technology without use to me. A part of it is a way to really accentuate certain aspects of the relationship, or the way in which we perform to one another, or the way in which life is seen, I suppose.

In terms of the way that… I mean, it’s hackneyed to say, but you kind of forget your body, unless something goes wrong with it. There is a kind of perpetual suspension of disbelief that’s part of just being able to function in the world. I presume that the first thing maybe that the work is doing is to break that to a certain extent, kind of almost perversely by being more artificial and excessively so. It breaks through a certain kind of barrier to another real that’s beneath a kind of banal experience in the world. There is a fresh attention that’s possible on what’s happening in the video, which is only possible. This is the thing that I have to presume. It’s only possible by doing this. This is the way to speak of something that is not there.

And by dent of that, it becomes more acute, I suppose. Whether or not that fully works and there’s a certain part of me that’s like maybe there’s too much in the show, even still. I know it’s a very Spartan show, to a certain extent, but it is very dense, you know? I mean [regarding] the video itself, The Worm… there’s something about computer generated animation that to me is immediately allegorical.

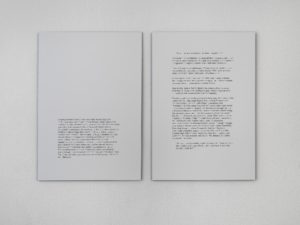

The Worm, 2021 (production still)

Video projection with sound, 12:40 min.

Image, courtesy the artist

Commissioned and produced by the New Museum and Nokia Bell Labs / Experiments in Art and Technologies

It feels like there’s some lesson to the whole thing. If only we could read it, if only we could understand what that kind of travesty of life is, that is being fed back to us by its attempted level of fidelity of representation. I think there’s something vastly melancholic in all of that, to me. And this is the gambit of my whole practice in a way, really. I suppose, it is that clinch, that moment of kind of, yeah, felt loss in the face of this stuff. And then using it to speak of essentially what me and my mother end up talking about is her mother. It’s an improvised conversation, in as much as any conversation, in as much as this one is right now. Although even more so because there was no subject matter. We were just going to talk and see what happened.

Obviously, the whole thing is laced with anxiety that is coming from me wearing this huge rig and my mother knowing that I’m recording her. All of these things, this kind of meta layers of performance, anxiety and stuff. But I think at a certain point, maybe three hours of recording in or something, she starts just speaking freely and happily, because it’s not about her anymore. She’s feeling like she can talk about her mother. I think that there’s a metaphoric world there that’s opening up around the technology and its own sense of history and its own failures and references. And that of the lives we’ve led and the heredity between me and my mother and the technology.

There is a lot to it, I think. And then the rest of the show… this huge wooden nothing, the big structure, was a very instinctive thing. There’s a certain dumbness to it.

I mean that in the sense of a mutant, and it’s very dead. I mean it’s become a bit of a habit of mine, to sort of counter the excessive nothing of the computer-generated animation with overtly, excessively physical things in the space. Hence the used linen and the sagging embroidery, and this very hard push towards heavy material, I suppose. But then to push the hollowness of the image and then rhyme that with that of the space, with other kinds of spaces constructed like that with a certain kind of primal scene, I suppose, as well as the psychoanalytic aspect to the thing, which is both embraced and dismissed by the literalness of the box in certain ways.

And then [there’s] my father’s diary made illegible on the surface of the embroidery…

Like the technology in the video, I think it’s safe to say, that the audience cannot read it. In the end it’s unavailable. There is an unavailability to it, but that unavailability changes with a loss that is irrecuperable that’s part of the whole thing. But also, with the intimacy that you are privy to in all of this. I’ve gotten, I think, show-making rather than just discreet works. The whole thing is hopefully in concert, in some way.

BL: So, exhibition making. I was very fortunate that while working at MoMA, I saw a lot of artworks and met a lot of amazing people. I want to know about, because it’s very much present in this work, the connection to the work of Dennis Potter, who was considered one of the most important creative figures in the history of British television. The wonderful man suffered from very painful psoriatic arthritis and died 1994 at the age of 59, which is, relatively young. As a child, did you watch Potter’s work? I believe it was very present on the BBC.

Singing Detective TV Guide image.

EA: I have some vague memories of the Singing Detective. That [drama series] was his big hit and it’s still probably his best thing, really. But that last interview [made by Melvyn Bragg with the dying playwright,] was the first thing I properly engaged with, actually. It was less about him as a figure than him as a body and as a very alive person in that interview. I mean, I’ve subsequently watched as much as I can and it’s an extraordinary body of work. But I still feel that that interview and that he himself is the apex of the whole thing. I mean, there’s a kind of lesson to that. This is the wrong word, isn’t it really? But there’s something important to be found in the achievement of him and the experience of the kind of privilege that we have in that interview of actually just sitting with him, to a certain degree.

And obviously, it’s again heavily aestheticized and mediated, but you get close to sitting with a person and them just talking, with the insane erudition. But for me, it was about him and the capturing of that person in that state, talking like that. And then [what] the world constructs around that scene. Again, the scene of it, inevitably attached to the scene of someone knowing they’re going to die. And what happens then? What happens? I mean we all know we’re going to die, but the way he talks about it is incredibly lush and romantic. And not necessarily like any experience I’ve witnessed of other people who are going through similar sorts of things or anything.

There is a theater to it. He’s really performing, but at the same time, you can feel the truth of it. You can feel this opportunity he senses in this interview to do this, to show people something in himself. And there are some areas of stability to it, to him. This is a final piece of theater and it’s glorious, I think. In a way, that interview’s been knocking around my work for years, I think really. Like most things, in a way, I’m making the same works over and over again in just different ways. Maybe I don’t know.

BL: It’s true that the interview with someone like that speaking could feel rote… Because they’ve often been asked the same questions. However, your version was very much a compelling conversation. And the reference, I thought, was very beautiful.

EA: Thank you. I think it was also important that I just wanted to talk to my mom, as well. In the end, after a lot of shifts in the project, it became inevitable and obvious that I would talk to her and see what would happen. In previous works the location of cliche and of presumed knowledge of the audience and stuff is also at work within the scene of the son talking to the mother. I think that there’s a lot of presumed cliche and rote-ness to that scene that, in a way, is also begging for difference, to be approached in different ways.

BL: I think it’s a very strong work and I really like the way you set it up, the way you created all of the amazing ancillary components. It’s gorgeous and it’s very moving.

EA: Thank you very much, Barbara. Thank you.

BL: Well, I’ll now go to my last question. It’s something I’m asking each of the guests in my podcast series, season two. Given the ups and downs of the last eighteen months and the struggles we’ve all faced in trying to adapt, how has technology affected you and your practice in the last year and a half?

The Worm, 2021 (production still)

Video projection with sound, 12:40 min.

Image, courtesy the artist

Commissioned and produced by the New Museum and Nokia Bell Labs / Experiments in Art and Technologies

EA: I suppose that video, The Worm, is a little essay about that, in a way. But as much as like everyone, I don’t suppose my experience is wildly different than anyone else’s in terms of just more increasing technological reliance. Things like this and spending more time on the phone, and more time at the computer, and on and so forth. But maybe that’s also driven a certain kind of desire to move away from it, a bit more.

Well, I think more than that, there’s something that’s awful about a lot of technology. That it really is a very lonely place. It’s about being alone with the tech and then with millions of people potentially. But there is something essentially alone about the user and the hardware.

I think in a way, I felt a real desire to work with other people. I think that’s also part of the pandemic, but I do think technology’s maneuvering to the individual user. I don’t really know… Obviously there’s a lot of massive online multiplayer worlds, or social media things. But they really are still contingent upon the individual in front of the computer or the phone or whatever. I don’t know, that’s felt acute, and a desire to just try and work on things with lots of other people, if I can. Stop working alone so much, I think.

BL: Does that mean we’re going to see you do some theater?

EA: Yeah, that’s coming up. Me and a dear friend, a poet from New York by the name of Steven Zultanski, are doing a play called Sorcerer that will debut at Revolver, Østerbro Theater in Copenhagen in March 2022. That’s very exciting. We’re just about to start talking to the actors proper. It’s a world that neither of us really know anything about. But we’re both incredibly excited about the script. They’re being incredible, allowing us—this sort of pair of ignorant people—to come and ask things. But also cinema: I’m really trying to get off the ground a proper feature film. And hopefully working with people in different situations as well. That makes it sound more interesting than I mean, actually. What I mean is, working with musicians a bit, just trying to keep doors ajar, feeling the canvass effort the pinch of the boringness of one’s own brain, how predictable I am to myself. And I think finally, breaking the deadlock and wanting to work with other people and have other experiences.

BL: Wonderful. Well, thank you so much for taking the time. It’s been great talking with you. Thank you so much.

EA: Likewise. Thank you.

Support for Barbara London Calling 2.0 is generously provided by the Kramlich Art Foundation.

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

The series is produced by Ryan Leahey, with production assistant Vuk Vuković. Web design by Sol Skelton and Vivian Selbo. Special thanks to Lee Ranaldo for graciously providing our music.

This conversation was recorded October 13, 2021; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Images

Venice Biennial, 2019.

Courtesy the artist

Venice Biennial, 2019.

Courtesy the artist

Video still. © Ed Atkins.

Courtesy of the artist, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Cabinet, London, and Gladstone Gallery.

Video still. © Ed Atkins.

Courtesy of the artist, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Cabinet, London, and Gladstone Gallery.

Video Still. © Ed Atkins.

Courtesy of the artist, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Cabinet, London, and Gladstone Gallery.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vM0hHSKfZw8

Image, courtesy the artist

Commissioned and produced by the New Museum and Nokia Bell Labs / Experiments in Art and Technologies

The Worm, 2021 (production still)

Video projection with sound, 12:40 min.

Image, courtesy the artist

Commissioned and produced by the New Museum and Nokia Bell Labs / Experiments in Art and Technologies

Singing Detective TV Guide image.

The Worm, 2021 (production still)

Video projection with sound, 12:40 min.

Image, courtesy the artist

Commissioned and produced by the New Museum and Nokia Bell Labs / Experiments in Art and Technologies