Today I’m calling Bani Haykal. Born in 1985 and based in Singapore, Bani Haykal straddles the world of language, art and music. As a media artist and teacher, he picks apart the nuances in our technology-fueled lives. In Singapore, he grew up listening to American rap music, eventually finding his way to avant-garde multi-instrumentalist Anthony Braxton, architect and composer Iannis Xenakis, and electronic music pioneer Daphne Oram. Bani’s interactive installation sifrmu version 5 is featured in “Seeing Sound,” a new exhibition I curated for Independent Curators International. The piece acts as an encrypted translation device, allowing users to explore the power of commonalities across different languages—but also the deeper power of incongruencies across those same languages.

Welcome, Bani. Thank you for joining today from Singapore.

Bani Haykal: Hi, Barbara. Thank you for having me. It’s good to be on the show. I’m really appreciative of being able to come on board and speak to you and speak to a wider audience as well.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: Perhaps you could start by telling me about the Southeast Asian collective Media/Art Kitchen. How did it come about?

BH: I think Media/Art Kitchen was the first group exhibition I participated in—the first time I got to meet a lot of different artists and curators from around the region. Media/Art Kitchen was more of a traveling show that emerged sometime in 2013, and I believe it lasted for a couple of years. It became a collective in the sense that there were the same curators and the same artists traveling together during the active years, although some changed.

BL: Were there particular issues that you all as Southeast Asian artists shared?

BH: More than anything, we gravitated toward this notion of the kitchen, what it means to play with material, and how we look at some of these ideas. I wouldn’t say there was cross-pollination, because there weren’t any direct collaborative efforts among artists. But in terms of the conversations and the brief residencies or programs that happened, we had the opportunity to interact with other artists and get to know each other a lot better. If anything, the focus was very much centered around this idea of what new media art practices were.

Joining the project, there was a bit of anxiety on my part because I had never identified myself as a media artist, or a new media artist for that matter. Seeing all the other artists and the range of works that were presented—from Ryota Kuwakubo’s Tenth Sentiment, which was a really elegant piece of work, to someone like Duto Hardono—it was a very, very exciting group, and I felt a little bit out of place, particularly because the works I traveled with were musical instruments I was developing to create new music.

I think a lot of it was also that everyone, including the curators, were navigating and trying to find new orientations as to what it means to enter into this domain of new media art. A lot of my interest in notions of interactivity was reignited over there—this notion of performing with an instrument or finding your way through an instrument, which in itself is a form of interaction or interactivity.

BL: When we met several years ago in Singapore, you showed me your visually stunning but wacky-looking electronic instruments. You made them by repurposing and combining old guitars, old typewriters, even old bicycles. It appeared that you were using these unusual instruments to improvise like a jazz musician or a rap musician. Was that in your mind?

BH: This interest to create new musical instruments wasn’t fully thought through in the beginning. I think my interest to dive into more extra-musical activity happened probably sometime in 2011 or 2012. My background at that time was mostly as a musician performing original music that I wrote together with my band. We went through a period where that wasn’t going to happen for some time, so this got me going in a direction where I was interested in finding other ways that I could create music outside of my comfort zone. That’s one way of putting it.

From that point on, it was just like one rabbit hole after another of figuring out what skillsets are, what harmony is, and more unchartered territories like graphical scores, and later new musical instruments. I think at that point one of the most pivotal composers that I came across was Harry Partch [1901-1974], who spoke a lot about his interest in new intonation systems and about how he developed instruments in order to perform or to play his pieces. A lot of that influenced my own interest in new musical activities, and because there was this desire always to create music, I thought maybe that’s an interesting starting point, to create new instruments and find what are other dimensions or other means of expressing myself through what music could be.

Sawed off electric guitar, with additional tuning pegs and fixed bridge; violin bow; drum sticks; small wooden peg.

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Used fixed gear bicycle

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Typewriter, contact microphone, boss rc-20 looper

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

BL: Is this something particular to the music culture of Singapore? Is this something you were deeply embedded in? I know you said you had a band.

BH: I guess my opinion is that music in Singapore hasn’t changed much. I still think it’s fairly dynamic. You have quite a wide range of different practitioners from musicians that participate quite actively with popular music or more mainstream musical expression, to the more experimental, more left field side of activity, so it’s pretty dynamic in that sense. You have a good mix. Regardless of our size, I think it’s relatively healthy as well. There’s a good amount [of activity] in each of these circles.

My interest was really to step outside the audience that usually listens to the kind of music that I’d been doing, interested to see what the other side was. In a sense, my introduction to making music wasn’t exactly within the realm of the experimental or the [extemporaneously] improvised music. My music was still very rock and roll on some level. Then later on, this interest to step away was so that I could find a new way to express how different sounds could be organized together.

In Singapore, because it’s a relatively small scene, in terms of performance, it wasn’t that difficult to try to find new audiences, or even to make claims that, “Oh, I’ve got something new that I’ve been working on.” There’s still a small and supportive group of people interested to see what are the new activities going on within the scene.

BL: Maybe you’ve already touched on it, but I’ve read how you’ve said that your love for music brought you to a place where music became the enemy. What do you mean by that?

BH: Over time, as you become close to something you start to become annoyed by it. At some point that really affected me, whereby the things that I ordinarily found pleasure in doing no longer seemed to make sense or were pleasant. Maybe I was also doubting what I was doing, as well. But a lot of it came from particular reading, research I was doing about jazz music during the Cold War period.

My late father was a jazz musician. He was playing a lot of jazz at the time, Wes Montgomery and so forth. Growing up in that environment, not that I was only invested in that kind of music, but I wasn’t very much exposed to other kinds of musical activity. Because of that, when I dived into this paradigm of what jazz music was like during the Cold War, the internationalization efforts and so forth, I realized the weight and the complexity of what it meant to experience a cultural product.

At that point it opened up this new head space, this new understanding of what are some of the various tentacles that thread themselves to something else, and how it’s part of a wider web of politics or ideas, I suppose. At that point, it dawned on me there’s actually a lot more that comes with these cultural products. Maybe it came at a rather late stage in my life or in my practice, but better late than never. Thinking about it then got me really motivated to think further about how else music plays a part in the ecology of cultural expression.

BL: Over the last few years you’ve been learning to code as a means of understanding and connecting with technology. You’ve also noted that you’re terrible with coding. I wanted to know how that is coming along.

BH: I stand by the fact that my coding skills are quite terrible. It’s very clunky and awkward sometimes. It started actually sometime between 2015 and 2016, when I was given an opportunity to do a project that involved collaborating with different groups of people and was very excited by that prospect. In fact, for the first few years of my practice, all I wanted to do was to collaborate with different groups of people. For the first three or four years, I had the opportunity to collaborate and practice with theater groups, dance groups, mostly people within performing arts.

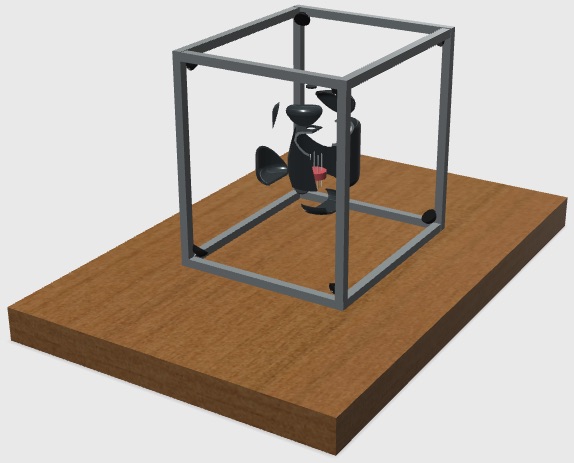

When this [new] opportunity came around in 2015, I thought to myself, “Maybe I would like to collaborate with people who don’t necessarily participate within the art scene or the art world…” It was also during the thick of this research on culture industries that I was developing a work called necropolis, for those without sleep. In a nutshell, the work revolves around two machines, two machines playing a game of chess. They’re sort of fighting each other for very long durations. It’s sort of like durational performance.

Custom designed mechanical Turks, computer-programmed chess game, 3D printed chess pieces and jumpsuits; TV monitor, CCTV and texts digitally printed on A4 cardstock; cut-up A4 photo paper with frames; rubber ducks.

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Custom designed mechanical Turks, computer-programmed chess game, 3D printed chess pieces and jumpsuits; TV monitor, CCTV and texts digitally printed on A4 cardstock; cut-up A4 photo paper with frames; rubber ducks.

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

For this particular work, knowing what I wanted to do, I worked with a robotics engineer, who is also a product designer, and worked together with a game developer and a game designer. The three of us sat together and started to put this work together. During this period of time, I was very excited by what coding and programming offered. From that point on I thought, “Maybe it’s something I should study.” I started picking up pure data, which is free software, and I struggled a lot with it. I remember going crazy at one point. Even if it was a simple function or a simple thing to do, I just could never figure out how to get it to work. It was a very trying period. But after getting past the learning curve, I realized how powerful this particular platform or this application is, and most of our work centered around coding.

It was during this period that I also understood the thresholds of my machine, and I think it was when I got quite a lot closer to my machine, in many ways. I understood what it can do, what it can’t do, how far before it tells me that, “Okay, you’re pushing me too far. I have to quit now.” All of these things were very exciting for me. I hope I’m not trying to humanize my machine in any way, but a relationship was established and my machine tells me when it’s enough, or it says, “Okay, we can still push forth.” A lot of the process of me learning about my machine happened during the process of learning how to code, as well as how many more things I could get it to run.

For the longest time, I think I never was interested in digital music or computer music, but getting into coding got me to appreciate what a machine was. At some point I was quite conflicted about this, whether it was my prosthetic or have I become the prosthetic of the machine. Through this interaction over the next few years, a lot of my work just revolved around getting the machine to do things that I think ordinarily I wouldn’t be able to execute. Maybe I think I’m a terrible coder, because of the way that I reason things out in my head, which is very messy. So, my machine is just as messy as my head.

BL: This brings me to another area. I think you also use language as a tool or a building block, but you’ve said that language is a musical activity for you. Do you want to say something about how language and the spoken are incorporated into your practice?

BH: One of the things that I got into, from 2011 onwards, was how I split my practice in two. On the one hand, I was focusing on what else music activity could become, or could go towards; the other side was really thinking about the other component of song writing, which was text, the lyrics that come with it. It was something that I did when I was playing in the band. I wrote the music as well as the lyrics. Another part of my practice was just to focus on text, which was when I had a crossover into the literary arts and spoken word performances, where the focus was primarily on how I would deliver a set of text on stage.

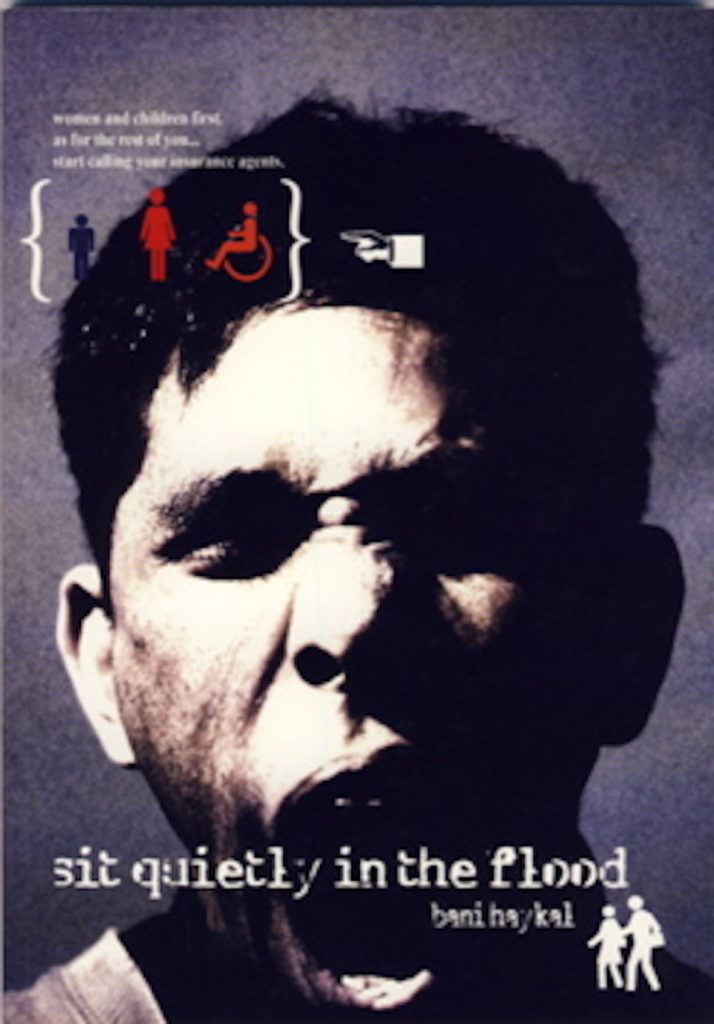

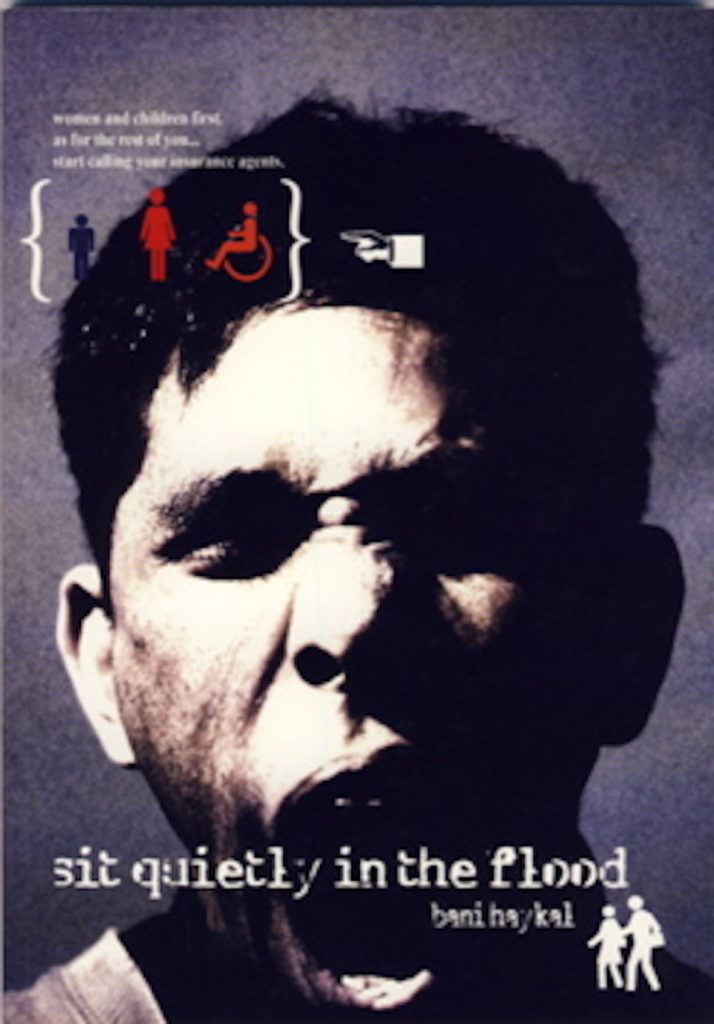

text/description of Publications: Sit Quietly in the Flood_11-17;

It was quite liberating to think about how I could distance the two, or how I could separate the two. Because then, I felt text on its own had a musicality that I had never really thought through before. Before, words had always accompanied songs or accompanied a melody. When I stepped outside of that, when I had that chance to just focus on text, I started to write in ways that allowed me to recite text or to perform text in a more musical fashion. That’s one way of putting it.

It took me a while to develop this particular way of delivering text. At some point the texts that I’d been writing focused more on rhythm, as opposed to melodic or harmonic content. That for me was quite exciting, because rhythm is a bit of a kryptonite for me. I am not a very rhythmic, very well coordinated person in that way. Getting into text as rhythm was a very exciting exercise, if I can say that.

It was exciting because suddenly I’m not performing like a beatboxer, where I’m producing all these progressive sounds or different textures with my voice, but using words and texts specifically to be able to do just that. That for me was a direction that I was consciously trying to work towards. How could I just write text, or how could I utilize text and make it musical on its own without having to supplement or accompany it with anything else? Everything became a very rhythmic exercise.

I suppose there are a lot of strengths that attach themselves to this line of thinking, from talking drums, for instance, and this idea of coded transmission. I think a lot of these ideas manifested themselves into the way I think about language as not just sonic activity, but as musical activity, as well.

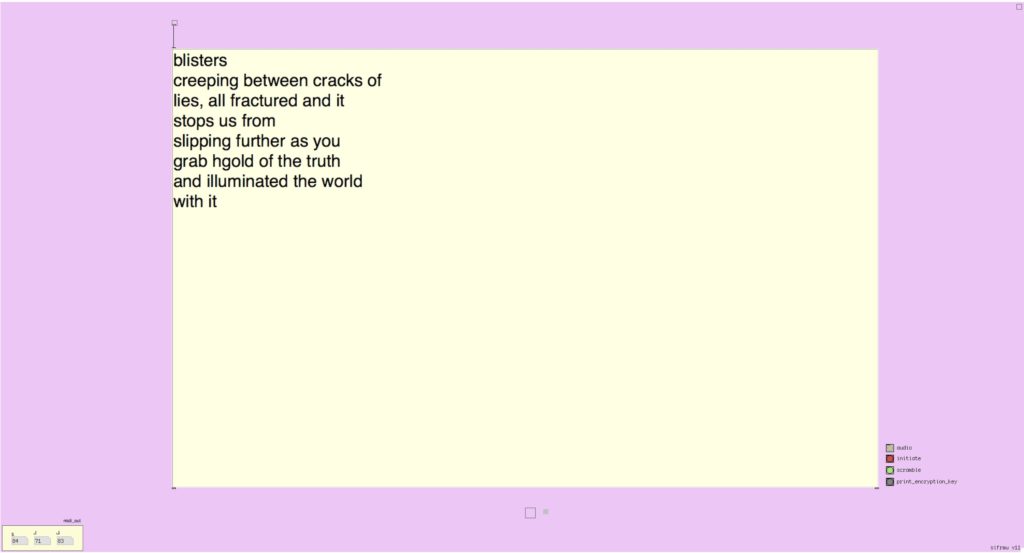

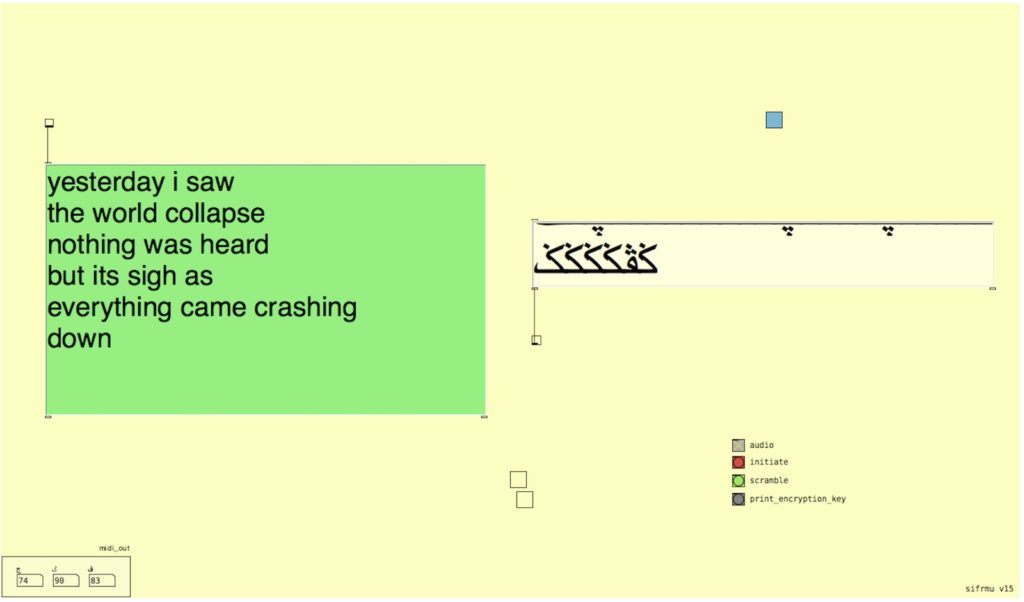

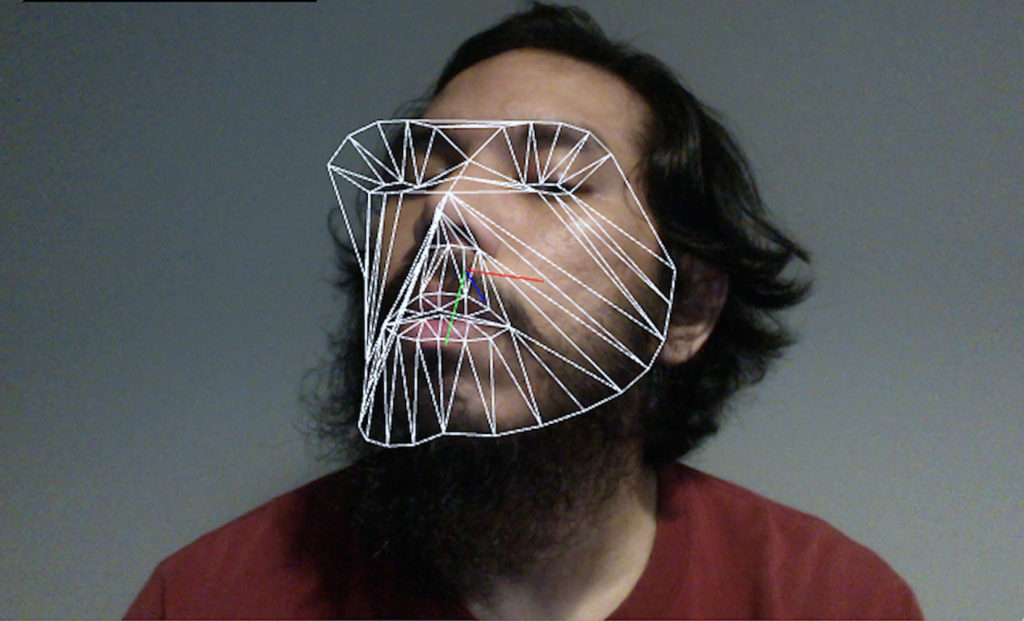

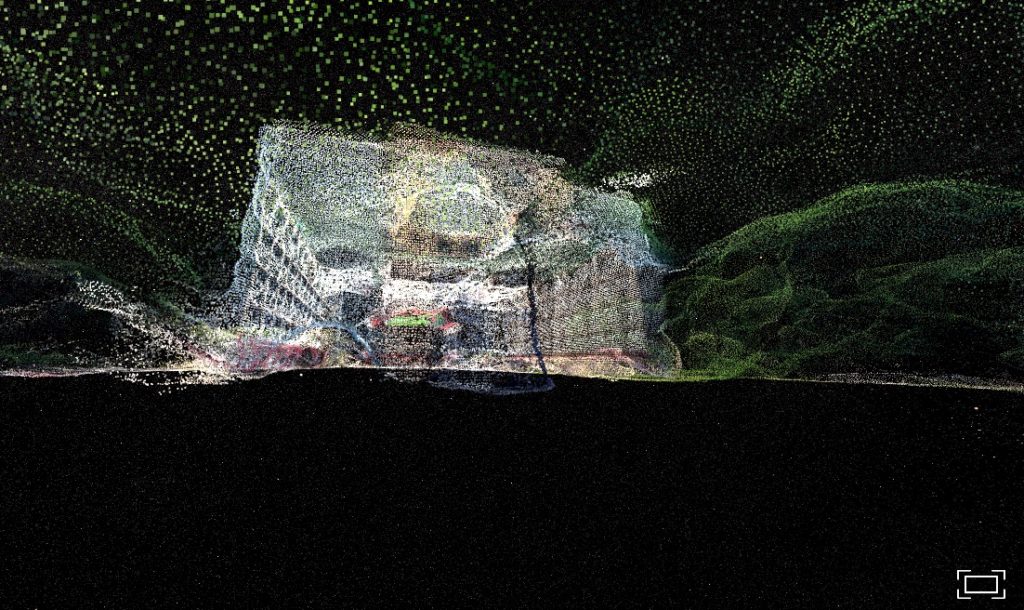

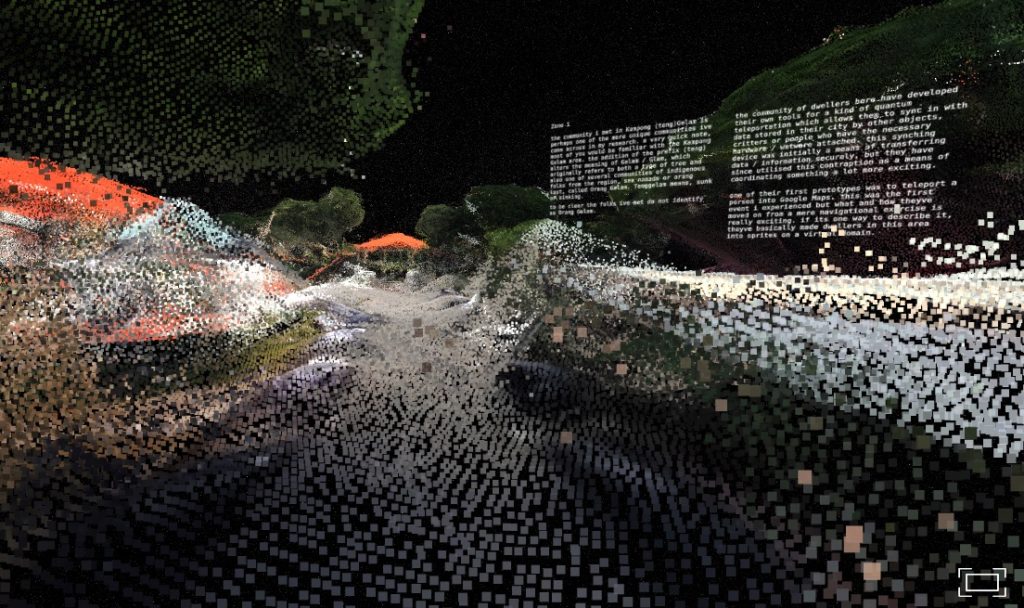

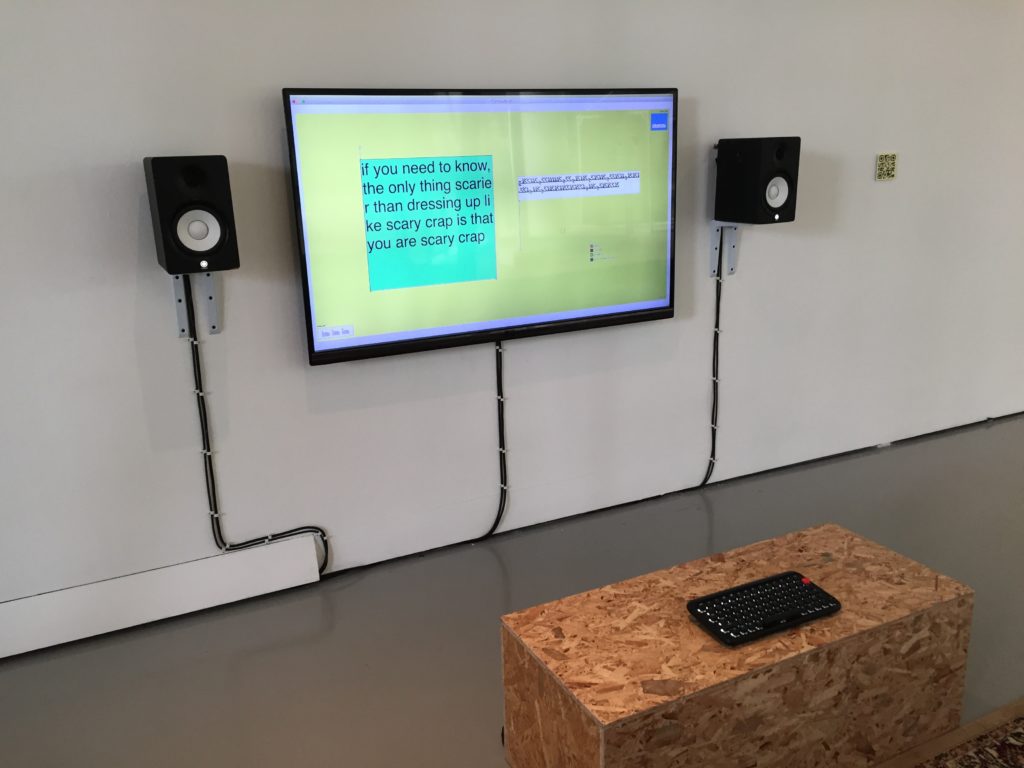

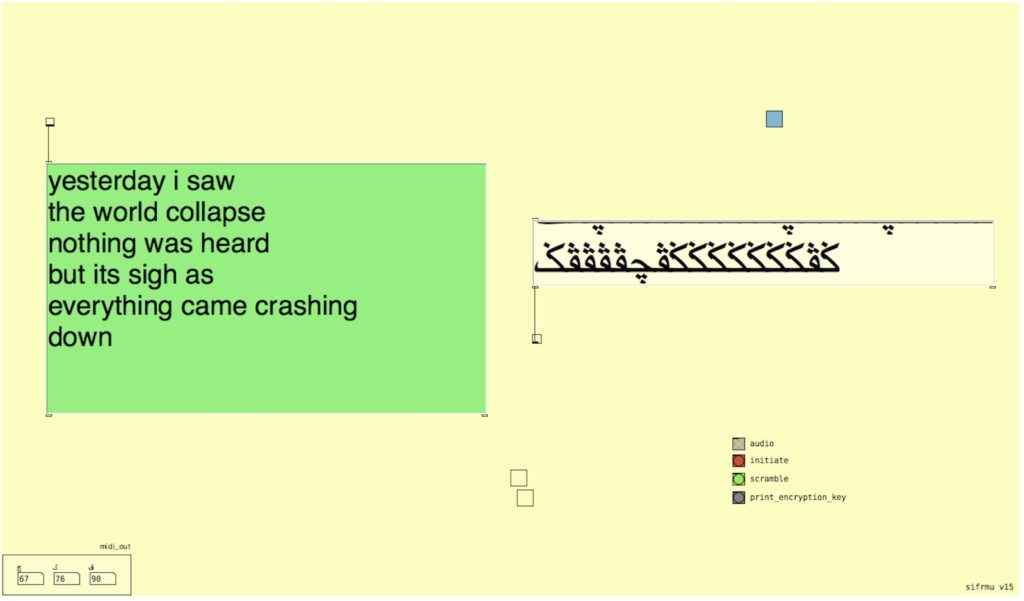

BL: From the recent book that you sent me, I read that you’ve thought a lot about language, and how language is the starting point for imagining the future. Then there are the English words that don’t exist in the Malay language. Code and language have a symbiotic relationship in your 2019 work, sifrmu version 5, which is featured in the exhibition I organized, “Seeing Sound.” There are many questions to ask you about this work. How does the project serve as a kind of encrypted translation device? The viewer or user walks up and is able to type a sentence. If I type an English sentence, your code and your device gobbles this up and out comes Malay as a text on an adjacent screen. There’s also a sonic element. It’s not a meat grinder, but a sentence has gone through a translation device.

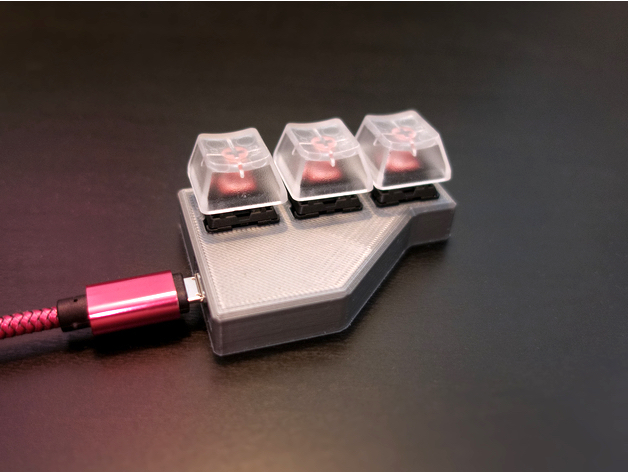

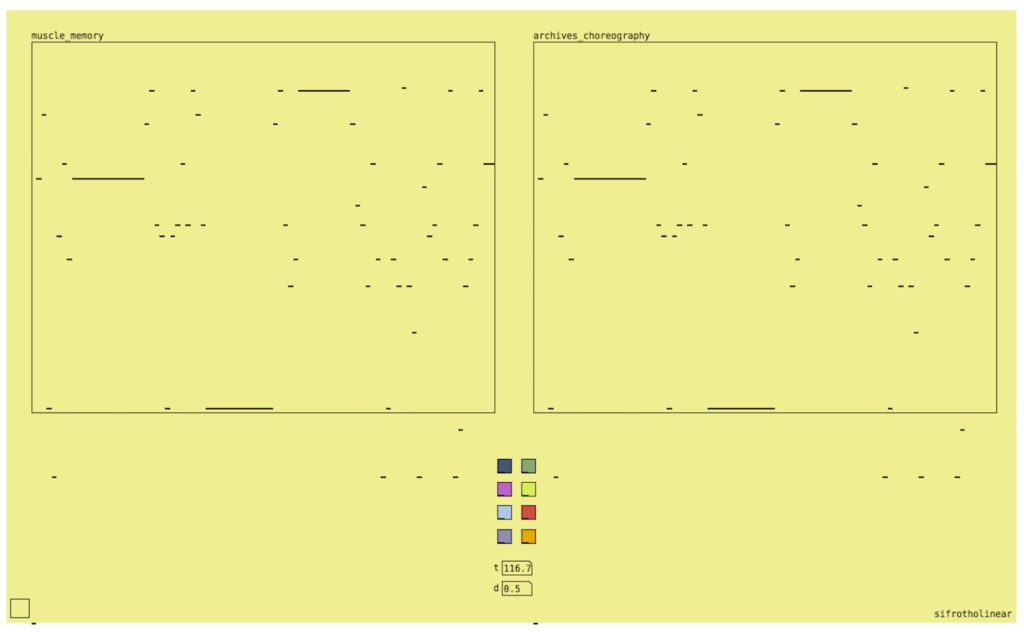

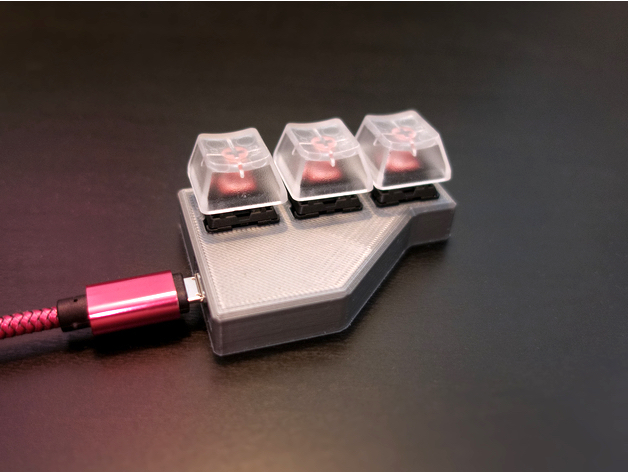

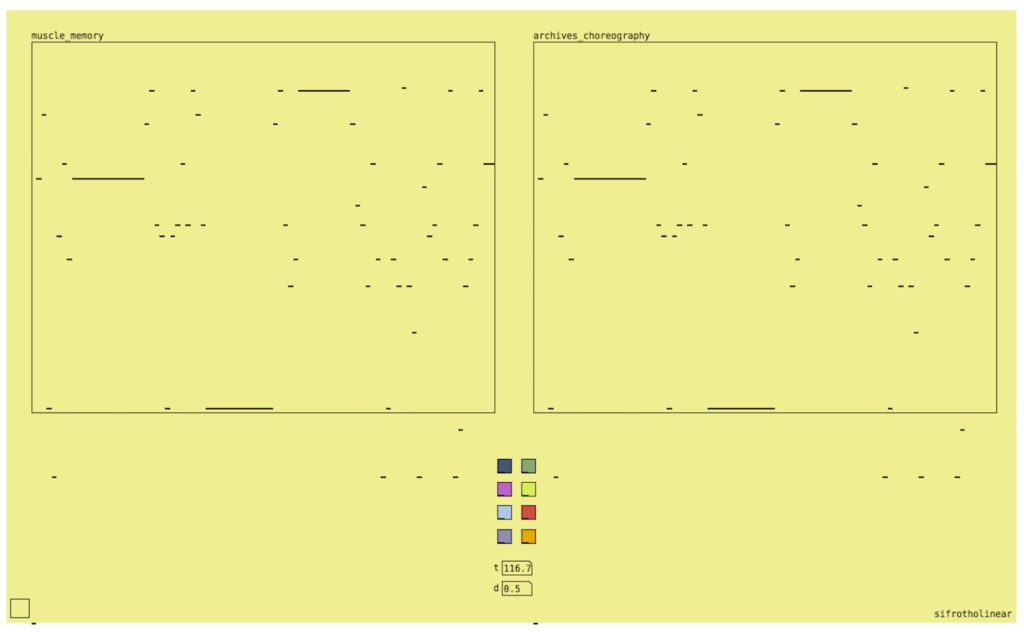

sifrmu patch, 2-channel audio, custom 75% ortholinear keyboard

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

BH: One way that I could start talking about this is maybe through the title itself. The title of the work is sifrmu, sifr, well, sifar. The reason I omitted the vowel between the F and the R has to do with the relationship that Malay has with the Arabic language. There are some borrowed words from Arabic that Malay utilizes. Sifar in Malay or sifr in Arabic mean the same thing. They both represent the numeral zero. Sifar is zero. And Mu means you or yours. In a sense, the title loosely translates to “your cipher.”

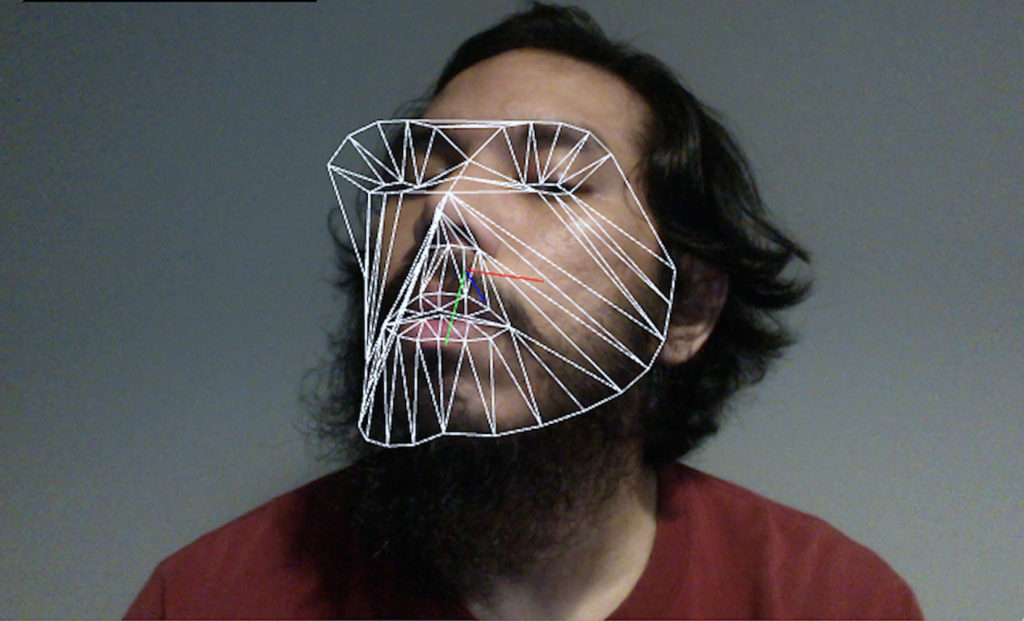

For this particular work, I think in many ways it’s definitely an amalgamation of all these different strands of interest and research coming together—playing with language, playing with sound, thinking about the organization of sounds. But more specifically it stemmed from the relationship I have with my machine. I’m more interested in thinking through what human machine relationships or human machine kinships and intimacies are like. That’s the starting point of this particular work—what are the gestures that we share, how do we become intimate with each other, and so forth.

With sifrmu, one of the reflections that I have about this work is quite typical of a lot of Muslim families in Singapore, be it Malay Muslims, Indian Muslims, and even Chinese Muslims. One of the things you grow up doing is recite the Koran. What’s fascinating and also intriguing for me about growing up doing just that, is that I can definitely recite the Koran, but I have no idea what I’m saying because I don’t speak Arabic. It’s not a language I’m familiar with, but I can definitely recite it. Recitation is not a problem, but reading it is a completely different thing. I don’t think I ever read the Koran, I only recited it.

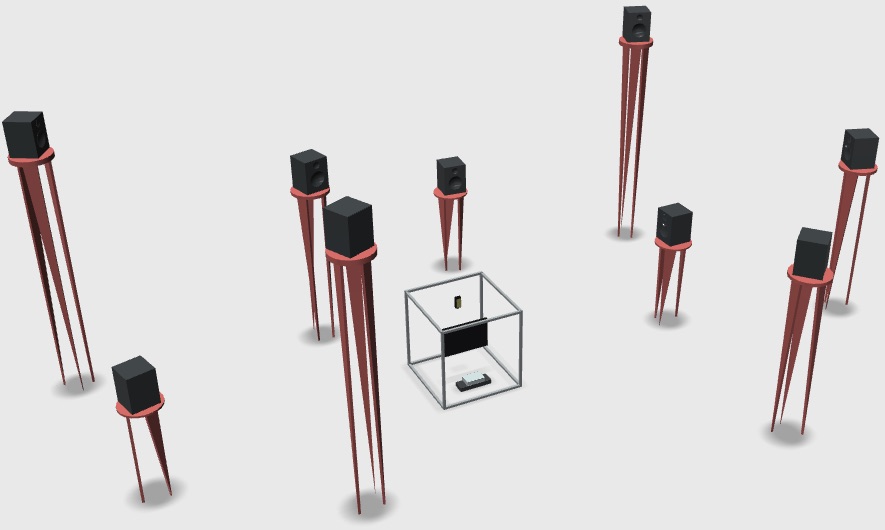

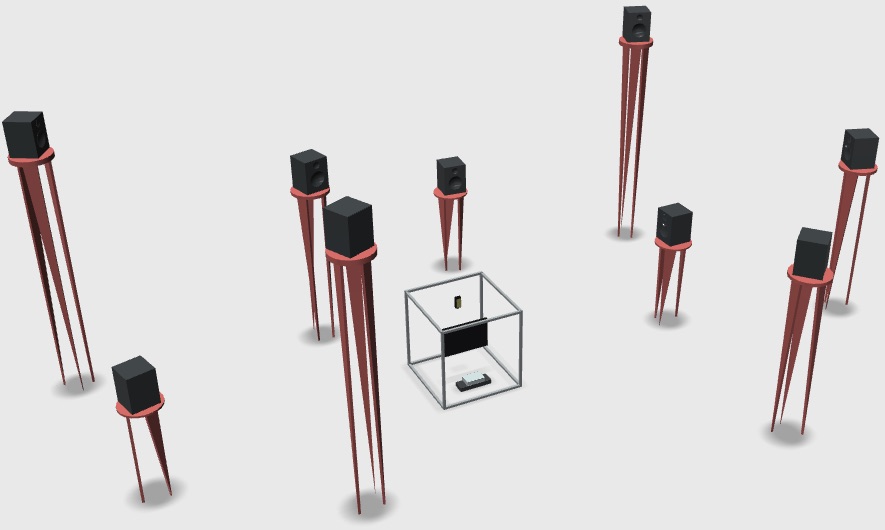

9 channel audio, aluminum, LCD screen, sifrmu patch, studio monitors, gurney sacks

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

That kind of experience from childhood is something you carry with you for a long time. I was reflecting on how that is, in a sense, a very musical experience or a musical gesture where you’re reciting, you’re interpreting scores and you’re just expressing them. For me, it’s very similar. I can’t read musical notations, but if I look at a score and I want to interpret it, it’s the same encounter I have with reading the Koran. I could definitely recite it no problem.

The meaning itself is something that is absent in that process of reading or reciting the Koran. That memory, I would probably say, is the earliest memory of musical performance I made to parents and to God. I’m just performing a musical expression at that point in time. I think that’s definitely something that circles this work, a fair bit. What is this musical component to recitation, to just reciting text, which in many ways is detached from meaning from the person reciting it?

With sifrmu, I was thinking a lot about this gap: this absence of meaning between machine and end user, human and machine, the things that we understand and the machine may not necessarily. These gaps happen, but at the same time, they are also evolving. The [machines] are also performing these commands that we’re telling it. Most of sifrmu revolves around this premise that encryption, or the way that we encrypt information across bodies, is more a process of intimacy or the process of knowing the other. This is where I hit my first obstacle in terms of trying to understand what this notion of intimacy is. What is intimacy? I think that’s one of the bigger questions that I’ve been struggling with, and that’s where I return back to the Malay language, which helped clarify this particular question or this particular position.

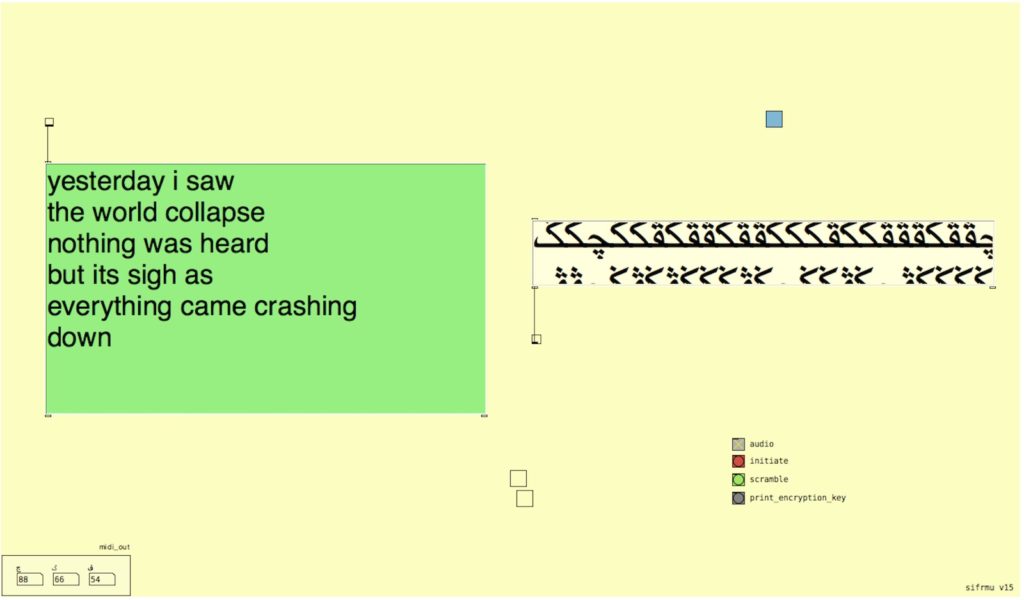

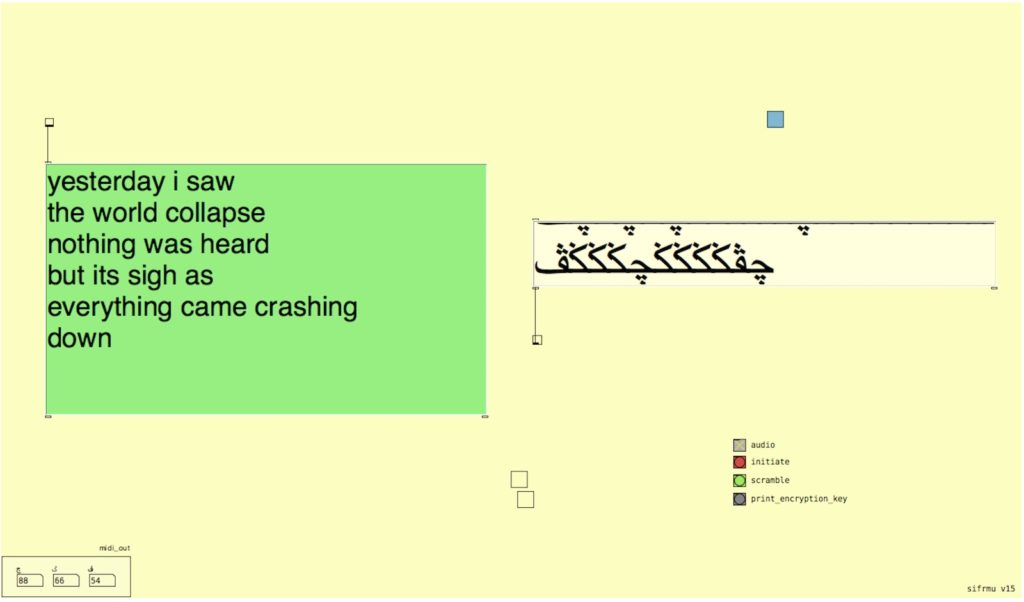

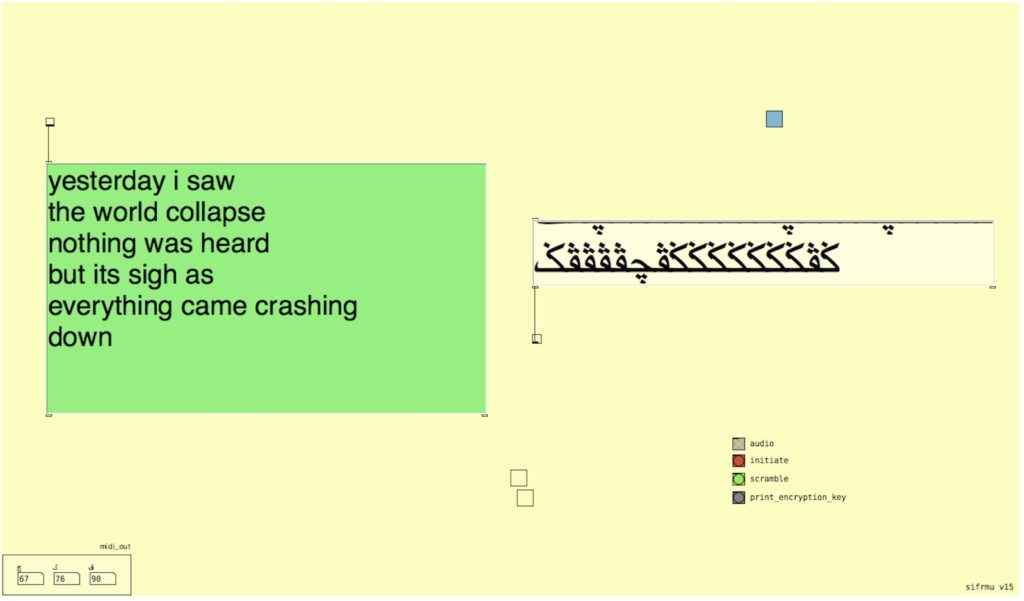

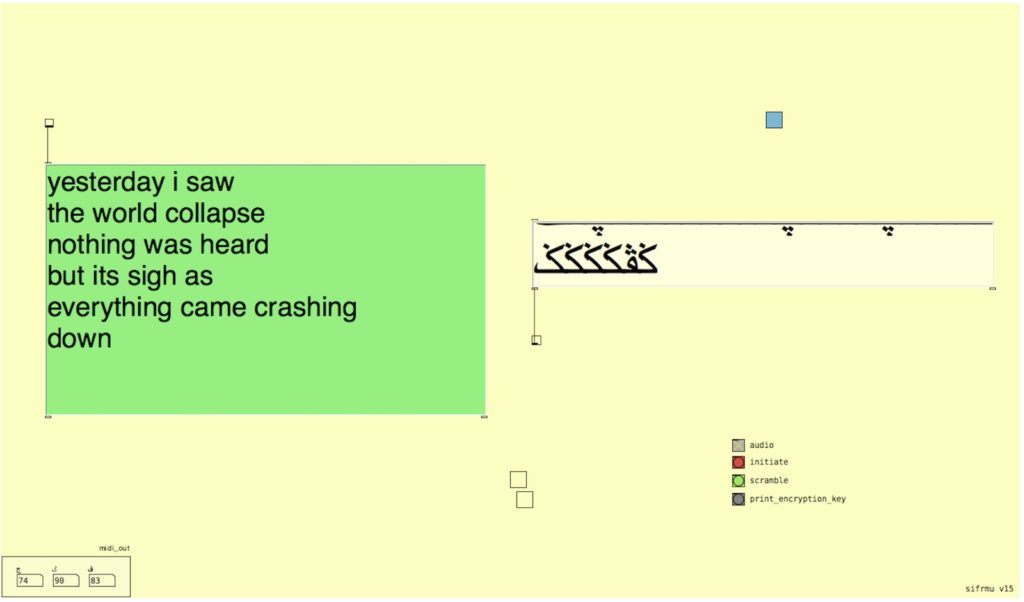

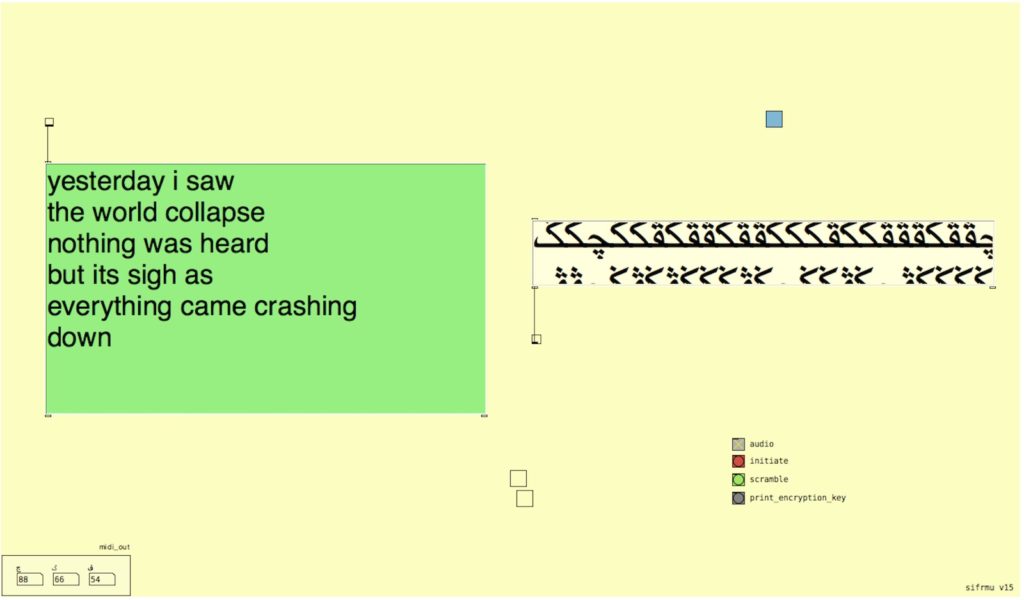

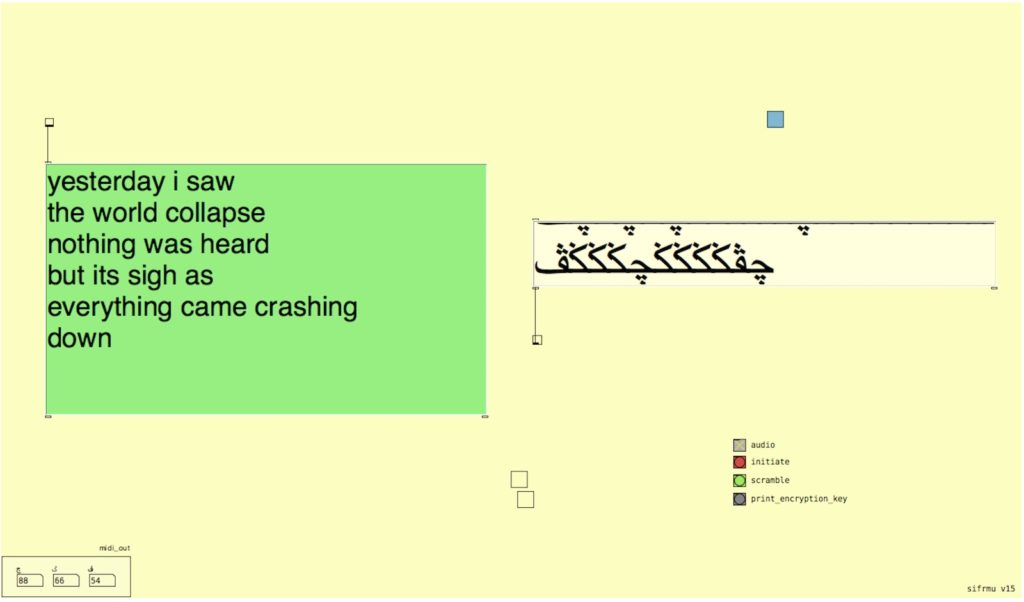

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

In Malay, we have an anglicized version of the word intimacy, which is intim. And intim means or represents exactly what you understand or perceive intimacy to be. But we also use a different word, which is mesra, M-E-S-R-A, a formal pronunciation. Mesra could be used in the context where you say, “Oh, these two people are very joyous or they’re very intimate with one another.” You could use the word mesra there, but one of its more prominent usages is in cooking. When I’m preparing a meal, let’s say I’m making pancakes. When you mix different ingredients together, your flour, your baking powder, and so forth, to create the pancake batter itself, we use the word mesra to describe a consistency, a kind of state that these ingredients would then become.

That for me was quite interesting, or very useful in thinking about what it means to be intimate or what it means to have intimacy with someone or something. It is to arrive at a transformed state, to transform with the other in order to become a new body or to arrive at a new state of together like pancake batter, having mixed all of the ingredients. This lends itself to I guess a more [Donna] Haraway [b. 1974] notion of cyborgs, where in this interaction, in this transformation that we have with the machine, we ultimately become cyborgs, or we’ve arrived at a different dimension altogether. It goes back to the idea, which of us is the prosthetic? Are we running the machine or is the machine running us?

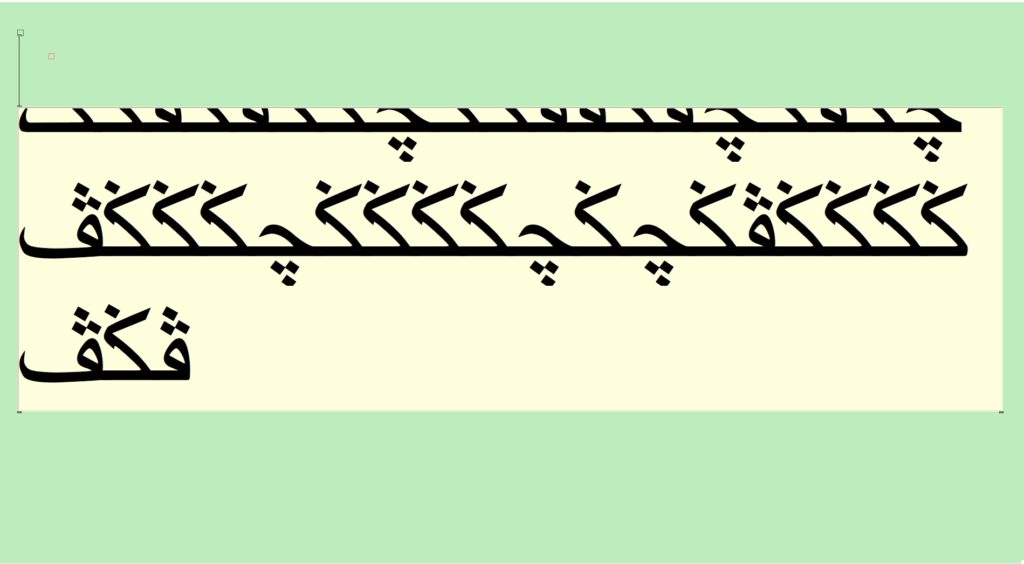

A lot of sifrmu has been helping me clarify some of these positions, or these ideas as to what this relationship is like and how we’ve not just grown close, but how we’ve merged, how we’ve become one with our machines. The process of this work, what you mentioned earlier on, what it does is when the user comes to the mechanical keyboard, they hear this click clack. (It’s become a new obsession, the keyboard.) The user approaches the mechanical keyboard and types in plain text in English, or in any language that uses the Roman alphabet. What my machine does or what the program does is that it encrypts these messages into a unique cipher text, a unique cipher.

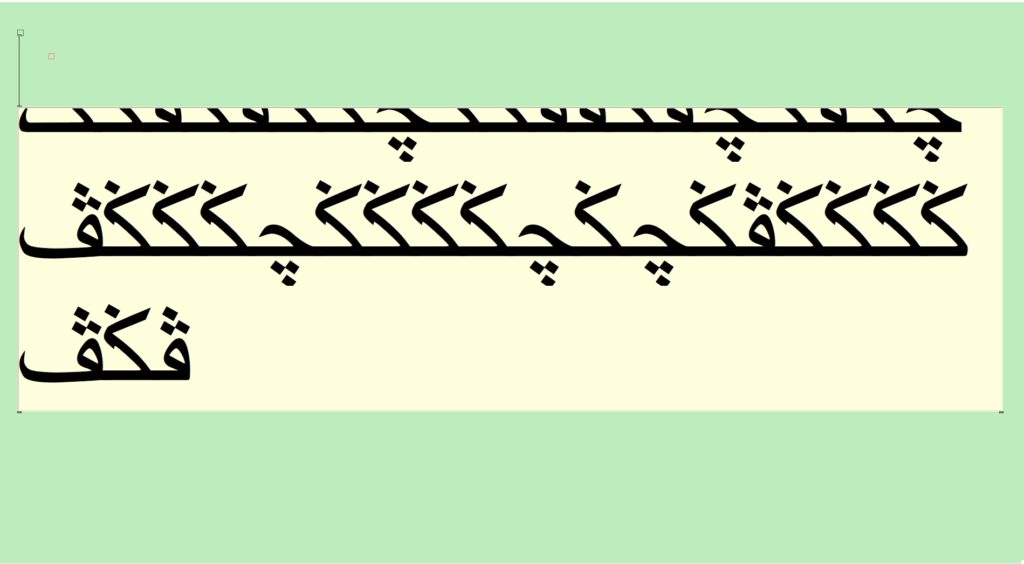

I resist the word cipher text because, in sifrmu, the cipher is in essence a combination of midi values, Jawi characters. Here’s another rabbit hole. Jawi was a written form that was used for Malay in the early 1900s and long before. It was stopped sometime in the early 1900s.

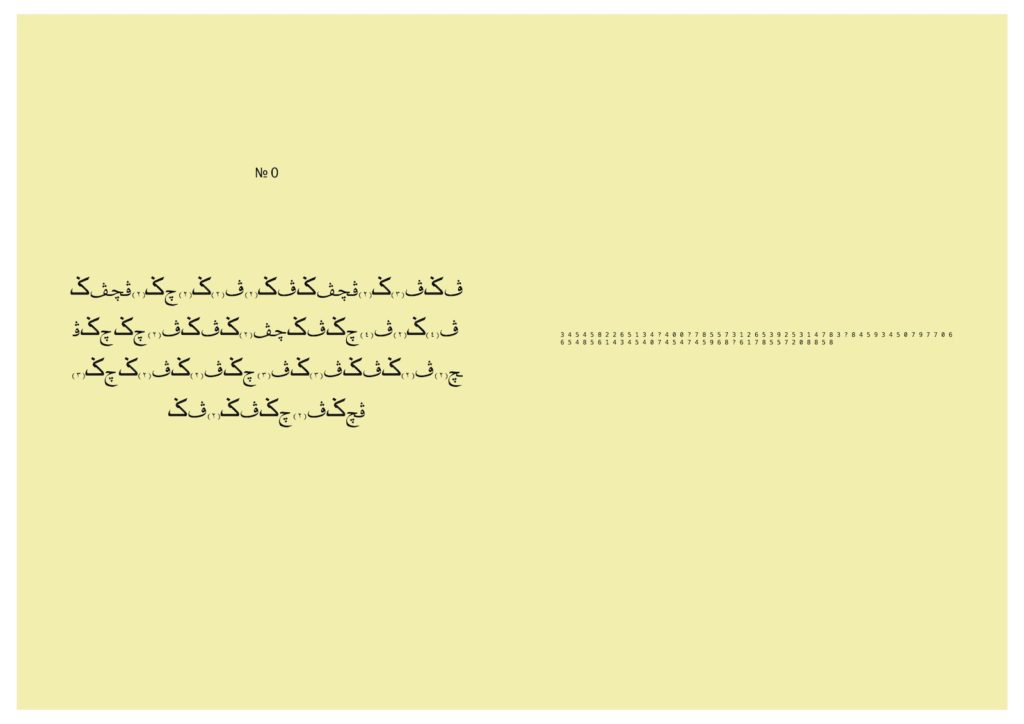

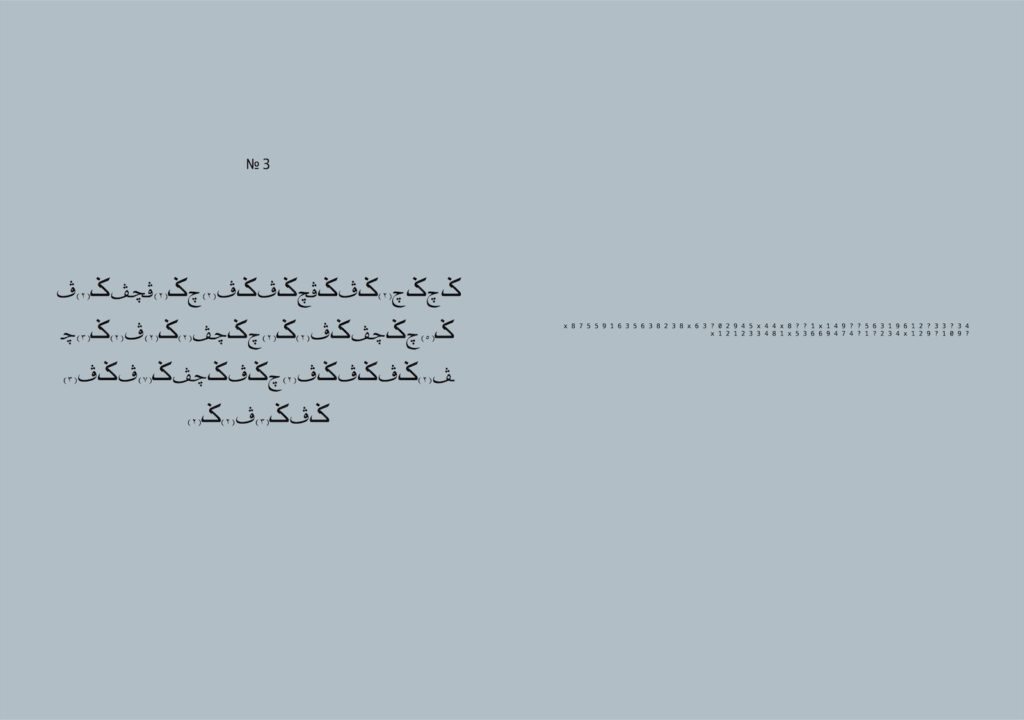

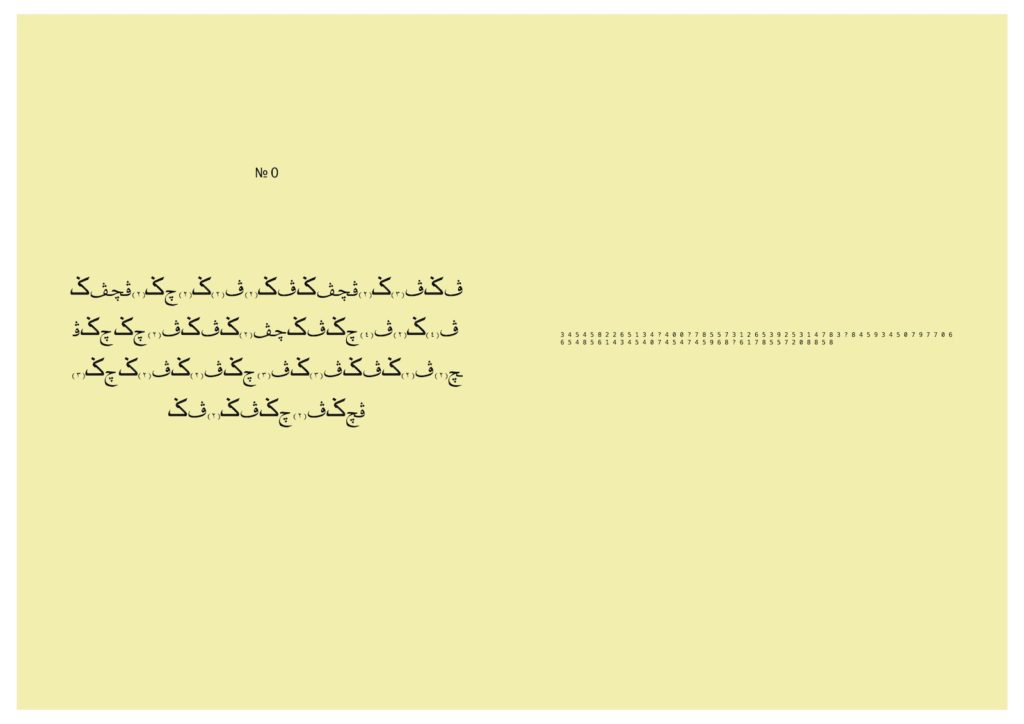

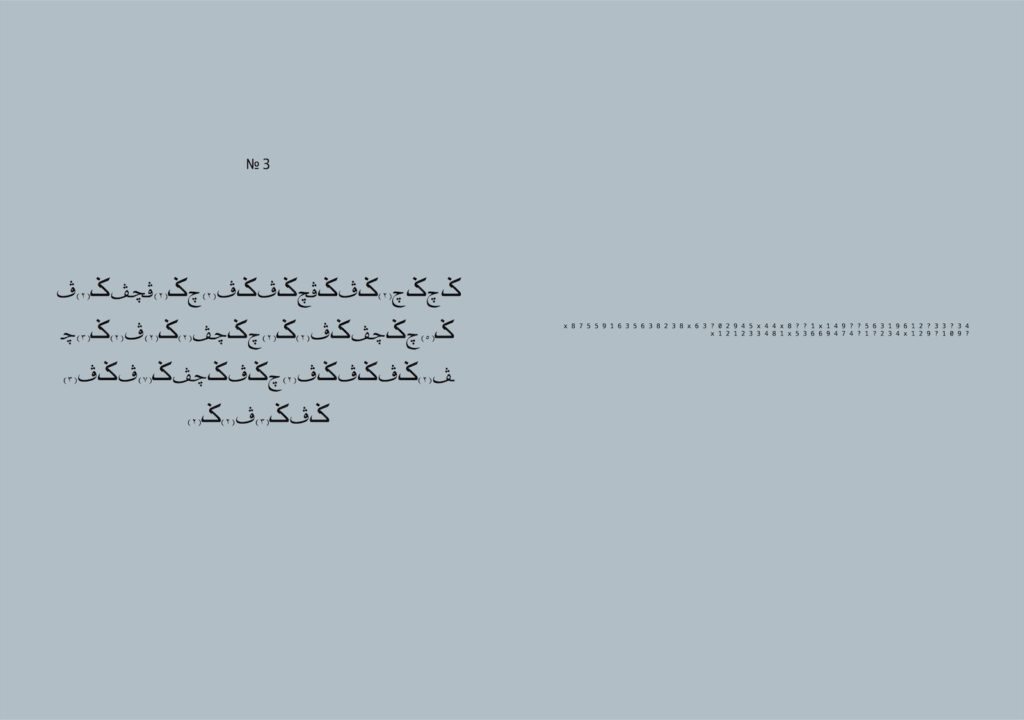

Digital Print, 21cm x 29cm, Ed. 10

Photo: courtesy the artist

Digital Print, 21cm x 29cm, Ed. 10

Photo: courtesy the artist

You can access archives written in Jawi of that period. What’s interesting for me is that whilst I do have training in reciting or reading Arabic script, I’m unable to understand Arabic. On the other hand, if I were to look at it in Jawi script, it’s not an issue. It’s almost like I’m reading Malay. It’s quite easy to understand for me.

I think the reason I wanted to use Jawi was to show some of these subtleties of where the lines are drawn, in terms of how one has access to a particular language, just by using these three unique characters— ca, ga, and pa—because they’re among the characters that don’t appear in the Arabic script. It was interesting to demarcate this particular language paradigm, what this particular cultural relationship is between my machine and myself, I suppose.

BL: Because the exhibition Seeing Sound will travel to venues in the U.S. and perhaps other parts of the world, how important would it be for the user operating your work to really think about the language or the script that you’re using?

BH: One thing that I was quite conscious of is that the interface is how someone looks at or receives the work. There is an immediacy to what one gets upon the encounter. You would actually see the script as patterns more than you would see characters that are appearing, because I’m only using three letters. And these three letters would repeat themselves constantly.

It becomes an exercise of looking at an image, as opposed to looking at a written language that’s unfolding. It’s very imagistic, much like desktop icons. You recognize what a file icon is, you recognize what the hard disk icon is. They’re just images for me. These three characters that I play with become just images, although they do represent something.

Jawi has six unique characters [Its other characters are borrowed from Arabic.]]. I’ve chosen three of them, which are ca ga and pa. These three consonants are present in Jawi script but not in Arabic script. In sifrmu the letters ca, ga, pa constantly make an appearance on screen. In a sense, all of these histories of what I just mentioned is my personal story. Ultimately the way that we understand our machines, as well, is through these icons or these symbols through which we enter into the machine’s world.

BL: I’d like to ask you about your teaching, your interdisciplinary electronic art survey course at the National University of Singapore. You wrote that the course is for students who may or may not have had any background in artmaking. What do you see as your goal for this class?

BH: I teach at Yong Siew Toh Conservatory, at the National University of Singapore (NUS,). This module that I teach is part of a minor in computer music studies. When I joined the program, I was asked to teach an introductory course that would be open to students in other fields, and that we could discuss music activity as being connected to other areas of artistic practice. Knowing that this particular course was open to the entire university, and not just limited to the conservatory, I thought was a really exciting endeavor.

What I set out to do with the course was to look at various artworks as case studies. It all begins from this notion of composition, or how composition is utilized in different processes in art making. What we study doesn’t conform to avant-garde musical projects, at all. In fact, one of the “art works” by Daphne Oram is an example of experimental music, a particular art practice, a particular musical project that we start off from. We look into works like Julian Oliver’s Harvest. Chrystelle Vu and Julian Oliver made a work entitled the Extinction Gong. So, we look at projects like these as a starting point to think about not just where music is situated, but how different threads of research or discipline come together to produce a particular work.

Students get a primer on how else music composition could literally be stretched to some radical extreme, so that it mutates into a different form altogether, which we don’t perceive as musical anymore. As part of this program, students are tasked to write a proposal for their imagined art projects. If they were artists, what would be an artwork be that they would like to create.

Through this entire process, we sit down and talk through what are some various threads that might lend themselves to their work, and challenge existing ideas. For the final presentation, they test one component of this proposal. It could be a mockup of one element of the work, or they might document something that becomes part of the presentation.

BL: You’ve said that Singapore is a suppressed and angered present. How is that for you, and is there something that music and culture can accomplish that nothing else can?

BH: Yes, Singapore is a very, very strange place. In this strangeness, we find ways to communicate, find different tongues, find different orientations, and find new ways of encrypting ideas and get thoughts across. The way that we engage and negotiate with one another has a lot of dynamism. If you go to my Twitter feed, you would see that I code switch a lot between what it means to speak about a range of subjects. It could be the simplest of ideas to the most complex political blah, blah.

For some of us at least, I think it’s a way that we found to be able to address both human rights issues and also cultural issues, in a way that allows for wider conversations. But at the same time, maybe there are more questions than there are answers, and maybe that need to resolve. I don’t know. Maybe it’s a generational thing. Maybe if it isn’t resolved, if it’s an answer that doesn’t come in this generation, maybe it comes in the next. If anything, that is the environment that I feel I’m navigating through in Singapore.

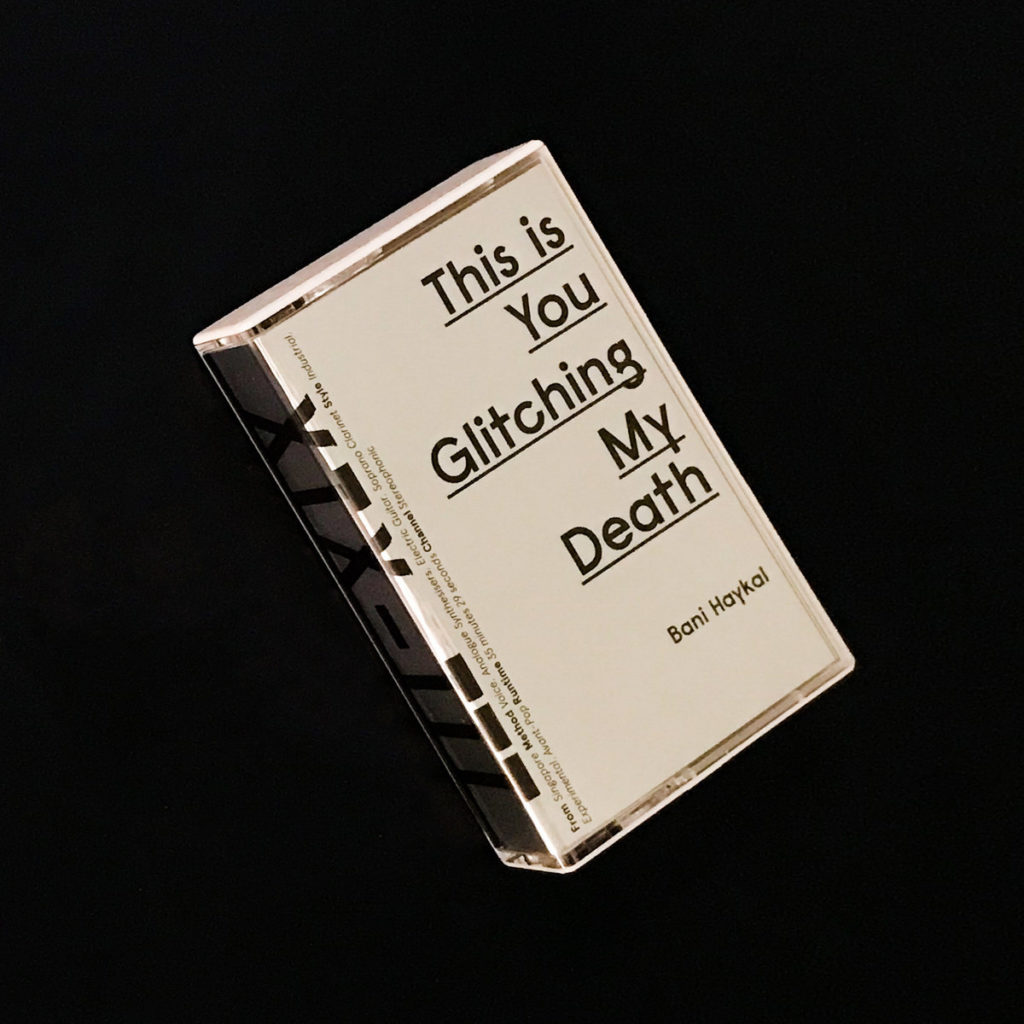

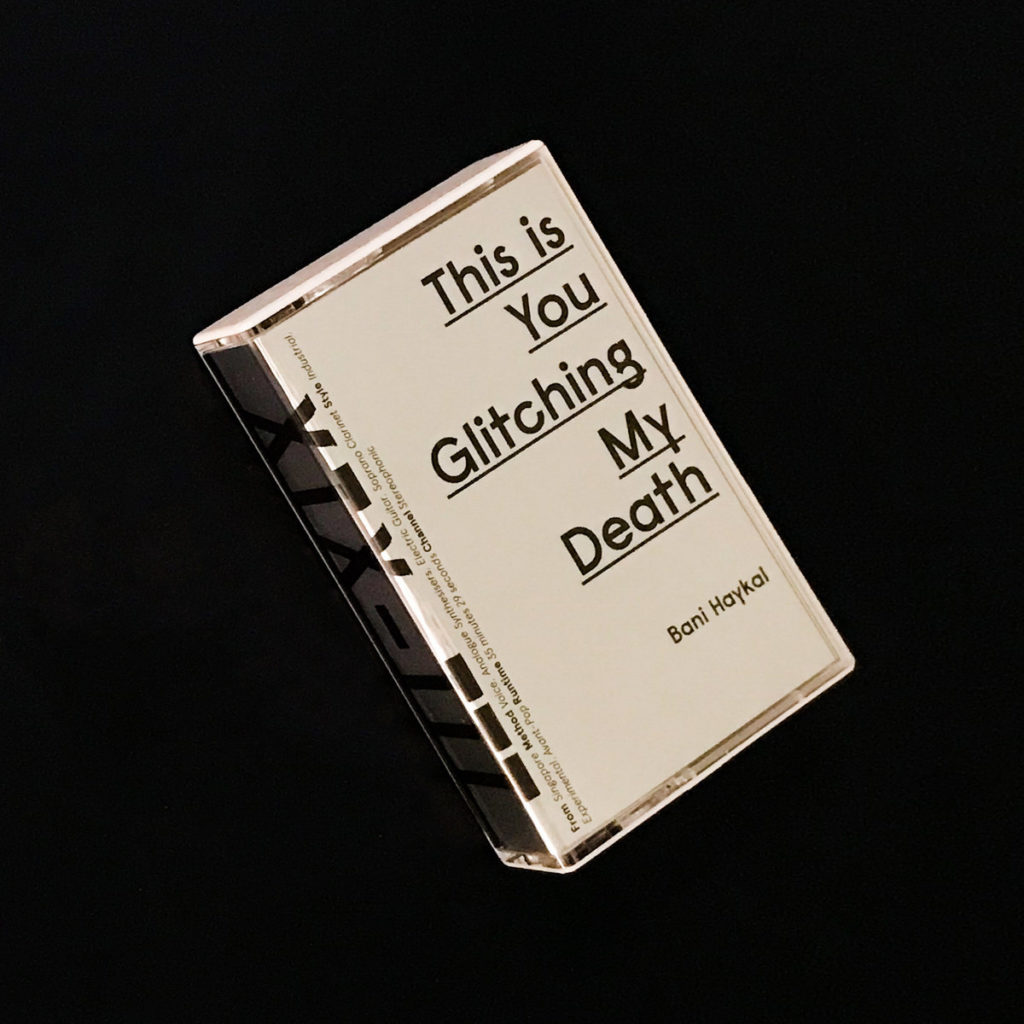

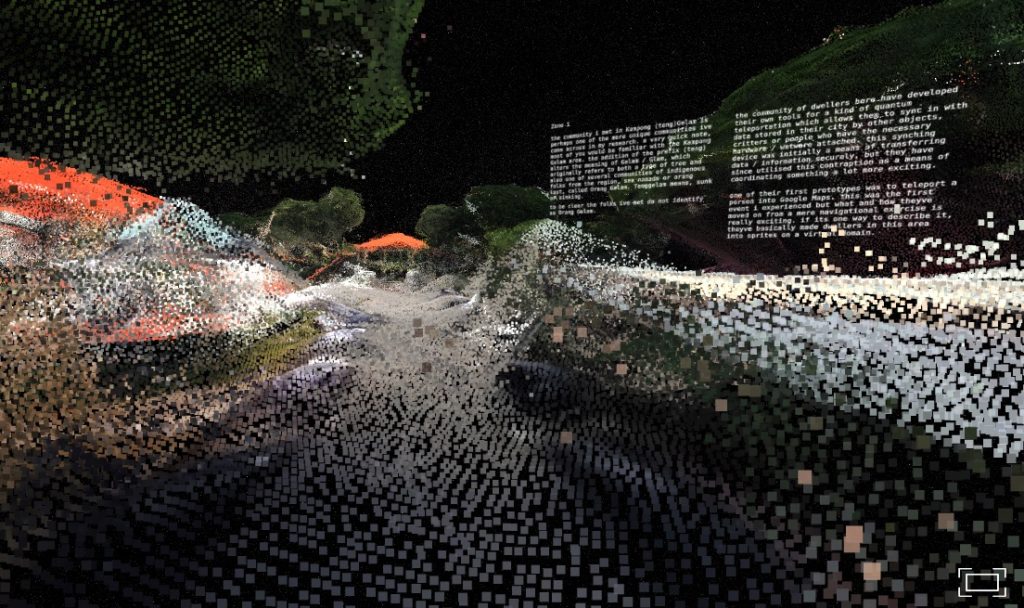

Duration: 32 minutes

Edition of 100

Photo: courtesy the artist

Duration: 32 minutes

Edition of 100

Photo: courtesy the artist

BL: Now, my next to the left question. You’ve said craziness is a requirement to dream a better future. How does that mindset fit with today’s craziness?

BH: This is a cultural joke. There was a film made in 2004. It’s called the Day after Tomorrow [by Roland Emmerich.] I never watched the film, but it looked terrible. When the Day after Tomorrow was screened in Singapore, the title given for it in Malay was just Lusa, L-U-S-A. Lusa is a Malay word. It’s a specific term that means the day after tomorrow.

In Malay, we have a word for tomorrow which is besok or esok, and we also have a very specific word for the day after tomorrow, which is lusa. But we don’t have a word for future. We don’t have an equivalent to what the future is. We have a phrase for it. We call it masa depan, the time ahead. But we don’t have this concept of what the future is. Or rather, the concept of future is different, at least, through the Malay language itself.

In many ways, this desire is to think about what time ahead is or what this future is. A lot of my recent activity goes through the Malay language, to unpack and investigate how else we think about time and how else we think about some of these very dominant horrors that we live in today. Even notions of intimacy, this idea of transformation made more sense for me in the Malay language than it did in English. Intimacy is such a vague concept. But in Malay, I understand it to be a means of transformation.

A lot of this messiness and a lot of glitches that happen across languages, I feel these are exciting. It’s just exciting for me to exist in these gaps and with these glitches, and find different ways to pull out of the present moment and think about the time ahead of what happens next. How else can we dream of different futures in the time ahead? If nothing else, I’m just very, very mindful that I don’t think that the future should be a singular monophonic environment for everyone. I think it has to be polyphonic.

There have to be multiple voices in the way that the future is envisioned, or in the way the future unravels itself for all of us. Across gaps, across glitches, your mind goes through so many different code-switching and meandering through these complexities and the greyness of language, the bluntness of language as objects. You need to remain very optimistic to reside in the space to move forward, I suppose.

BL: That’s beautiful. The last question I’m asking everybody who’s part of this conversation series, do you consider yourself a media artist? What does that mean anyway?

BH: I don’t know. I don’t know what it means. I don’t want to get into this whole “let’s unpack what media is.” All these interfaces and all these devices, they’re all media in one form or other. My 2013 experience taught me that even an instrument is media, or a medium, for that matter. I don’t know how to answer this question, Barbara, I am so sorry. But I would say that as someone that works with various media, or various mediums, sometimes maybe these things are using me. Like maybe I’m being puppeteered via these various interfaces and these different media to create something. So, I’m not sure how to answer this question. But I guess maybe I’m using them, and maybe they’re using me.

BL: Well to me, you’re an artist, and that’s most important.

BH: Thank you.

BL: Thank you so much. Thanks so much for sharing your ideas, you’re very eloquent and wonderful.

BH: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

—

BL: On behalf of Bani Haykal, thanks for joining us for this episode of Barbara London Calling. Support for Barbara London Calling is generously provided by Bobbie Foshay and independent curators international in conjunction with their upcoming exhibition Seeing Sound, which I curated. Be sure to like and subscribe, so you can keep up with all the latest episodes.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Bower Blue , with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music.

Thanks again for joining us. We’ll see you next time.

This conversation was recorded June 24, 2020; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Images & Video

Born 1985 and based in Singapore, Bani Haykal straddles the worlds of poetry, art, and music, and raises down-to-earth questions about our technology-fueled lives. With sound as his medium, Haykal has explored the development of music culture in Singapore, investigating its social relevance, developing a personal philosophy on music that includes the importance of reconstructing or rethinking present musical forms through improvisation, both aural and physical. He produces objects that allow his audience to interact and make their own music.

Haykal studied Interactive Media Design at Temasek Polytechnic, and received his MFA in fine art from LASALLE College of the Arts, 2019-2020. He is an adjunct lecturer at Siew Toh Conservatory of Music, which is part of the National University of Singapore. He teaches the Interdisciplinary Electronic Arts survey course and Sonic Environments. He has performed and presented his projects internationally, at the Wiener Festwochen (Austria), Media/Art Kitchen (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Japan), Liquid Architecture, and the Singapore International Festival of Arts. His interactive installation sifrmu version 5 is featured in “Seeing Sound,” the exhibition circulated by Independent Curators International between 2021-2024.

sifrmu

sifrmu is a portmanteau of two words: ‘sifr’ (Arabic / Malay for zero), which etymologically is the root word for cipher, and ‘mu’, a Malay suffix meaning you / yours. He started the project by looking into encryption as a process of intimacy, where information not meant for public access is hidden through various techniques, in order to protect the content of the information, an act where two entities blend together to keep one another safe. Begun in early 2019 while pursuing an MFA, he focused his studies on encrypting poems and other messages that he turned into both ciphertext and sound. The project revolved around creating a patch that would encrypt alphanumeric keys into a combination of Jawi characters and MIDI values, producing a multi-sensorial cipher consisting of text and sound. Jawi is an Arabic script for writing Malay, Acehnese, Banjarese, Minangkabau, Tausūg, and several other languages in Southeast Asia.

sifrmu version 5

The interface for sifrmu 5 is an encryption patch that turns plaintext into ciphertext. The project of encrypting messages/poems into both ciphertext and sound, involves a patch that encrypts alphanumeric keys and transforms a text into a combination of Jawi characters and MIDI values, a multi-sensorial cipher consisting of text and sound.

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

9 channel audio, aluminum, LCD screen, sifrmu patch, studio monitors, gurney sacks

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

4 condenser microphones, 8 ultrasonic speakers, ABS 3d printed parts, aluminum frame

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

sifrmu patch, 2-channel audio, custom 75% ortholinear keyboard

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

sifrmu patch, 4-channel audio, custom 75% mechanical keyboard (Cherry Browns)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

verses for a future

(sifrmu prints)

Having gathered a series of written texts in the form of prose and poetry out of his performances and presentations, Haykal selected ones that resonated with his work on encryption, intimacy, and the future. The texts were edited into individual verses resembling ones intended for prayer. As prints, they are presented in their encrypted form together with the key that was used for decryption.

Digital Print, 21cm x 29cm, Ed. 10

Photo: courtesy the artist

Digital Print, 21cm x 29cm, Ed. 10

Photo: courtesy the artist

necropolis for those without sleep

necropolis for those without sleep is a durational performance-installation. Two robots play a predetermined game of chess, which is game data collected over a period of several months when Haykal played chess with various individuals. The game itself is an odd variant comprising of White and Orange (as opposed to the traditional White and Black) where Orange consists of a Queen, a King and Pawns, whereas White consists of a Queen, a King, 2 Pawns and double of everything else. This work was a commission by Singapore Art Museum as part of their biannual President’s Young Talents series.

Custom designed mechanical Turks, computer-programmed chess game, 3D printed chess pieces and jumpsuits; TV monitor, CCTV and texts digitally printed on A4 cardstock; cut-up A4 photo paper with frames; rubber ducks.

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Custom designed mechanical Turks, computer-programmed chess game, 3D printed chess pieces and jumpsuits; TV monitor, CCTV and texts digitally printed on A4 cardstock; cut-up A4 photo paper with frames; rubber ducks.

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Duration: 32 minutes

Edition of 100

Photo: courtesy the artist

Duration: 32 minutes

Edition of 100

Photo: courtesy the artist

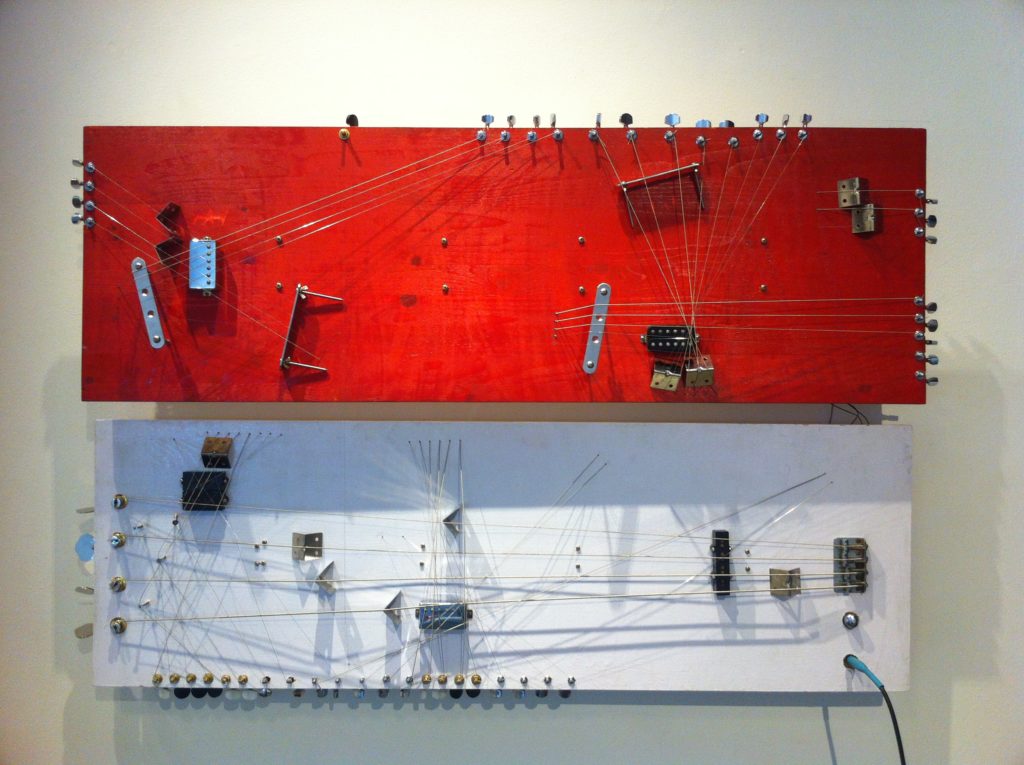

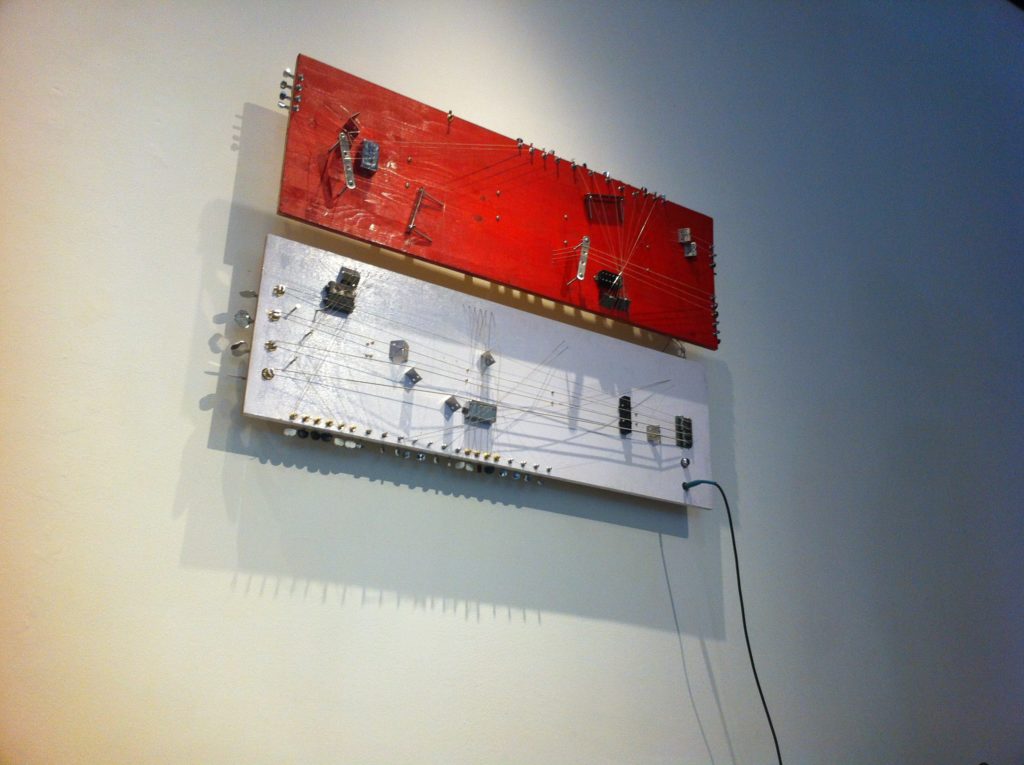

Dormant Music

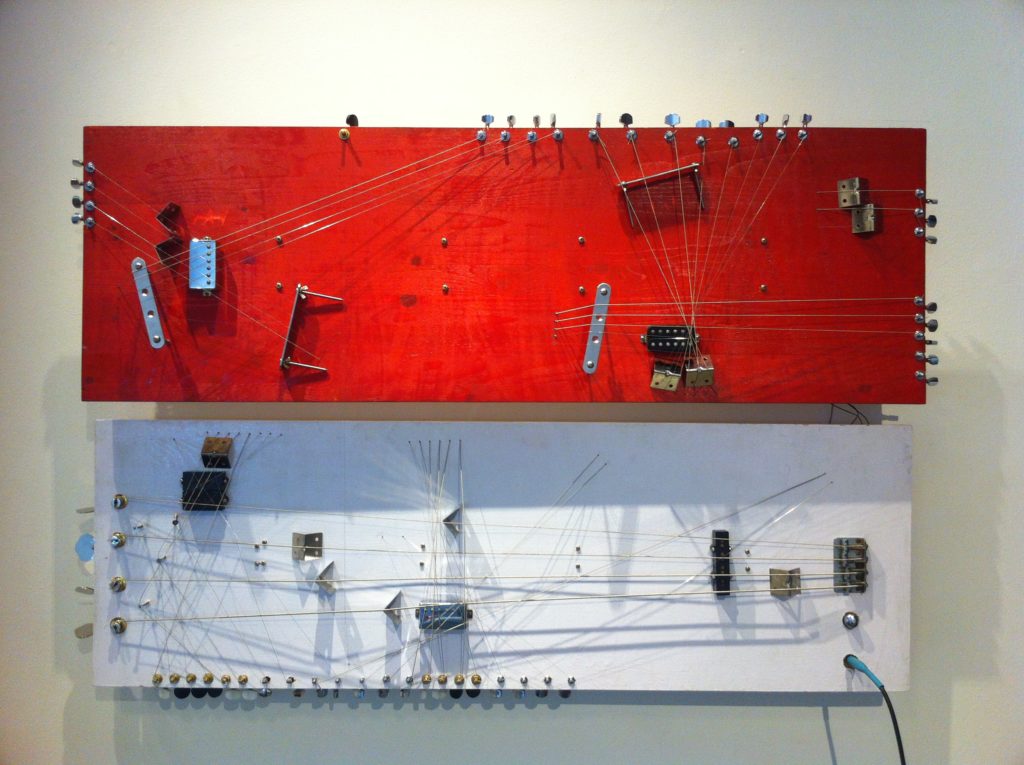

Dormant Music is a series of musical instruments that grew out of Haykal’s interest in finding new ways to interface and create musical expression. Begun during a residency at Platform 3 in Bandung, the capital of West Java in Indonesia, Haykal built a group of assemblage instruments in response to the city and to the constraints he encountered there. Something as simple as walking was a difficult endeavor, given the scarcity of sidewalks and limited roads conducive to walking. He cobbled together fanciful instruments out of what some might consider detritus.

His first works in the Dormant Music series explored the dynamics of navigating Bandung, a new city for him; the second series examined the political dimensions of harmony in Singapore. Works in the second series played with tension, dissonance and chance more explicitly, while still demanding that the public engage with these instruments on their own terms and with their own ideas of musicality.

Enamel paint, electric guitar, and bass pickup machine heads, bridge, electric guitar and bass strings on wood planks.

120cm x 39cm x 2cm (x2)

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Sawed off electric guitar, with additional tuning pegs and fixed bridge; violin bow; drum sticks; small wooden peg.

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Used fixed gear bicycle

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Typewriter, contact microphone, boss rc-20 looper

Dimensions variable

Photo: courtesy the artist

Publications

As a young writer outside the local literary scene, Haykal started out making eBooks and printing his own. He wrote a lot while serving mandatory national service, when he was stuck in an office doing mostly multimedia editorial work. Around this time, he joined a group of writers who critiqued each other’s work. The group eventually helped to get his first collection of poems published, Sit Quietly in the Flood.

Singapore: Word Forward, 64 pp

Photo: courtesy the artist

In 2013, Haykal was nominated for and won the Young Artist Award, organized by Singapore’s National Arts Council. For some time, he had been thinking about creating a book that would document his practice, with particular attention to his fascination with text / text-based processes. Putting the monograph together involved challenging some of his positions and ideas about text-based works and about how far he could stretch form. He began writing and experimenting with his premise of text as material, text as a manifestation of sound, and of text as a means of organizing sound.