Today, I’m calling Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, two London-based artists and collaborators with a background in installation art and the moving image. Iain and Jane began their fruitful collaboration as students at Goldsmiths in London, where they saw firsthand the good and the bad of the so-called YBA movement of young British artists.

Music has always played an important role in their work, culminating in their 2014 feature film, 20,000 Days on Earth, a musical docudrama starring the iconic singer/songwriter Nick Cave. Iain and Jane’s Requiem for 114 Radios, which features 114 vintage radios simultaneously buzzing and broadcasting, will be featured in “Seeing Sound,” an upcoming exhibition I organized with Independent Curators International (ICI). Iain and Jane, thanks for joining me.

Jane Pollard: Very welcome.

Iain Forsyth: Hello.

[Continue reading for full transcript.]

Transcript

BL: Your practice is so rich and varied. Let’s begin with how your collaborative practice began during your second year at Goldsmiths, University of London, where you were studying fine art and art theory. How did you get started working together?

IF: The very first thing we did together actually was a publishing project. We had both arrived at a point as students where we weren’t particularly productive. We weren’t producing an awful lot. As we got to know each other better, I think we both had an interest in a kind of culture of making things happen, a culture that, to me, certainly was more familiar in the music scene, the kind of DIY fanzine scene. It just felt like we could do something—we could make something happen, and there seemed to be no reason why not.

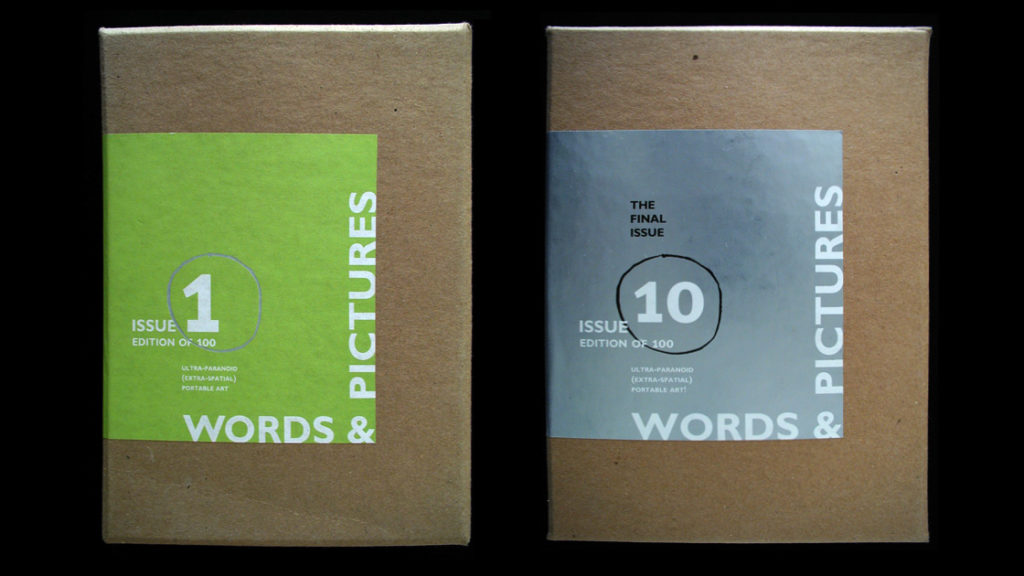

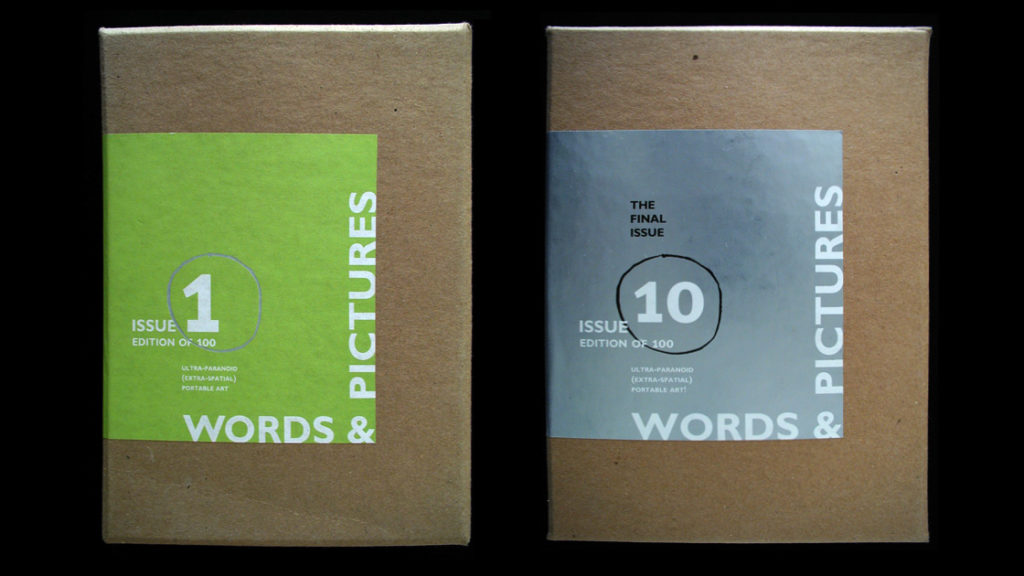

So we began publishing a magazine that was based on art objects. Contributors to the magazine would produce an art multiple, and we would sell them in curated boxes and they were published three times a year, from 1994 to 1997 or thereabout. We did ten issues in total.

JP: It was called Words & Pictures: Ultra-paranoid (extra-spatial) Portable Art.

Photo: Courtesy the artists

Each time we invited a musician or an artist or a writer to contribute both a preface and an another to do an introduction. And we worked with [the singer] Momus, who actually coined the title, Words & Pictures: Ultra-paranoid (extra-spatial) Portable Art. Momus wrote us not a manifesto, but like an erratum to our manifesto for our first issue. We launched it at the ICA [Institute of Contemporary Arts in London].

Let’s give you a bit of context: Goldsmiths was fallow at that point. The early 1990s was a strange period. In the previous six, seven years, there’d been such a rush of success for the really young artists coming out of the B.A. course. It felt like there was no sense of rebellion there. It was all about finding your thing and then doing your thing as best as possible, getting it ready so it’s ready for walls. We just had no interest in that. It felt so unexciting.

At the same time, we were going to a lot of gigs together and we both were benefiting from the nightlife that London offers you up as students. It felt like the way that small independent bands were able to connect to an audience—the attitude, the immediacy, the exchange of that—felt much more exciting. So, Words & Pictures started almost like a fanzine, but instead of writing about music, we asked artists to make multiples that could fit in the box and, together, started an interesting conversation.

BL: Talking with you and doing some background reading, you noted that Goldsmiths was a place to get angry and that most of your work was born out of that anger.

IF: I think it’s your job as an art student to be angry. I think that anger is the energy that gets you through three years on a B.A. or whatever it might be. Goldsmiths to us at that time, I think, just felt like it gave us so much to react against. It felt like being in the wake of the vapor trail of that YBA [Young British Artist] generation.

Looking back, I think a lot of our contemporaries were being prepared for the art market, and I guess the kind of interests we had were in a wider audience. It felt like a lot of the things that were being done at Goldsmiths were being made really for an audience of one, and that audience was Charles Saatchi. I think for us, as Jane was saying, the idea that a music event engages with an attending audience is probably what ultimately meant that the very earliest work we did together was performance-based.

JP: It’s worth saying, I grew up in Newcastle, and it wasn’t the dark ages or anything, but there weren’t any contemporary art galleries, not that I knew of. Baltic [Centre for Contemporary Art] didn’t exist. Sage [Gateshead music center] wasn’t there at this point. There was the Laing Art Gallery, where you could see old paintings. I didn’t really know that being a contemporary artist was a possible option. I didn’t know what that would mean. So, in the one year of foundation I spent in Sunderland [School of Arts and Cultures], my eyes were opened. I really began to say, “My God, this is something you can actually do, that you can be this.”

Coming down to London, I think we both came with a lot of energy, but also with a total kind of lack of understanding of the sort of existing hierarchies and structures of the London art scene or the art market. The people we wanted to speak to included anybody, people like us, young people. People that maybe like us didn’t know about contemporary art or weren’t visiting galleries all the time.

BL: You found great energy there.

IF: I think it’s good to have something to kick against. And I think Goldsmiths was for us, the perfect sort of springboard for wanting to do something other.

BL: Your sources of inspiration are quite diverse. Now we’ll turn to three people in particular to discuss today, Bruce Nauman, Joshua Compston and Nick Cave. Let’s start with Bruce. I know that while you were at school, you saw Bruce’s Good Boy Bad Boy from 1985, which was the first work of video art to leave a mark on you. I want to know why.

JP: Standing in front of Good Boy Bad Boy, I was laughing before I was thinking. I kept laughing. I was entertained. I couldn’t understand it. But it was affecting me on an immediate, instant visceral level. I didn’t even feel shut out from it. I didn’t feel like I needed to understand some kind of something clever or some sort of secret code in which to decode it. I got it. I got what he was doing and he was doing it again and again. And that repetition kind of breeds a sort of infectious humor to it. I mean, it changed me. That there are those works in front of which you are just transformed that you realize, what’s that? I can do that. He can do that. Then the sort of the possibilities of what you can even think about just exploded and you sort of go running through the open doors trying to kind of find your own voice in it.

IF: I think also it was a bit of a gateway drug, really. It sort of opened that door into a period of video art that hadn’t really been on our radar. It wasn’t really talked about, particularly in London in the mid-1990s. It wasn’t particularly fashionable at that point, and had a kind of Renaissance a little while later. But just starting to dig into some of that generation, and particularly discovering for ourselves the work of Vito Acconci, signaled so many possibilities that the galleries that we were able to access as young art students weren’t really presenting to us. So, a way of somehow looking back felt like a way of looking forward.

JP: Maybe there was also a kind of rhythm to the pattern of speech, definitely with Nauman, absolutely with Acconci, where they seem to be somehow borrowing something from music or from poetry or from the street even. There’s an accessibility but there’s also this kind of rhythm. And that was something we knew. We knew rhythm from music. We knew rhythm from the poets that we loved. I think that seeing that you could engage, that you could kind of borrow from other art forms and pull across and make something from them, but within the world or the language or the blank canvas of contemporary art, that was exciting. That felt really exciting.

IF: We’re practically pre-internet at this point in the mid-1990s. I think we didn’t get our first email address until 1998. So, this information was still relatively hard to access other than by spending time trawling through the college library. And it goes without saying that video art and performance art in books is not necessarily the most representative way to encounter it.

BL: So the second person I want to ask you about was, in 1993 you met Joshua Compston. He was an often irritating prodigy who came up with innovative curatorial ideas that would later be quite widely adopted. I gather he single handedly turned the down-at-the-heels London neighborhoods of Hoxton and Shoreditch into cultural capitals. How did he have an impact on your practice?

IF: Joshua was like a bolt of lightning. He just fell into our life out of nowhere and literally transformed it. He completely opened our minds to ways of thinking about art, engaging with a public art, art engaging with the streets.

JP: Art changing life. He was really excited about the idea that before him there was a whirlwind kind of impresario like Malcolm McLaren and these kind of big ideas, situationist ideas that were going to apply to contemporary life in London and youth culture. That’s what Joshua felt like. It felt like somebody kind of way ahead of his time or completely mad, who was constantly spouting and promising and dreaming. We were at Goldsmiths at the time, and I think in us he saw hunger, our kind of eagerness to do something or to practice in a way that is more accessible. I think also, on his part, wholly selfishly, he saw two people that he could use to kind of almost begin to archive some of these ideas.

So, we would meet on weekends with a tape recorder and have breakfast together. He’d just talk. I mean, we asked questions sometimes, but my God, he could talk. Then we would take the recordings home and on our tiny little word processors, we would type up transcripts and then we’d fax them to him and he’d amend them and we’d get them faxed back with all of these notes on them. We were making these recordings and documents that were charting his ideas of the time. Sometimes I couldn’t tell whether they were serious ideas or not. Some of the discussions that we had made it into printed, published articles in varying kind of independent magazines.

IF: I think one of the things he really shared with Malcolm McLaren was that idea that you can talk something to the point of it becoming a reality. And Josh was very, very good at talking a good game, right?

JP: Somehow, if you tell enough people, you are kind of implicating yourself into having to go through with it in some way, or that if it exists in enough consciousness, then it has to become real. You see it in the people that we met through him, particularly Gavin Turk. We were introduced to Gavin and Deborah and to Gavin’s work, which became really influential on us, in the kind of variety of kind of objects that he was able to create. And the conversations Josh was able to have with past art as well, I think that was hugely influential on us. Joshua’s influence is still there. There are ramifications of it, not just in what’s happened in Hoxton and Shoreditch but also in the people, the people that he kind of touched.

IF: That was one of his greatest skills, in a way—people. I guess the cynic might say he was a great manipulator of people. I would perhaps say he was a great coordinator of people. He was very good at sort of gathering around him a community of people who were not necessarily like-minded but shared enough objectives that he could kind of probably use them. To be fair, in a way he got something out of that relationship, but usually the person he was working with did also.

I think it’s something that we’ve taken forward in our way of working, that sense of a community around you, people that you can return to, you can work with and trust over and over and over again, I think that has become really, really important to us. Certainly, over the last few years, you can kind of see it in actors that we’ve returned to and cinematographers we’ve returned to. They’re very much a group of people that I now consider to be our kind of network.

JP: People were his currency in an odd way. I can tell you this, because he’s not around anymore. And data protection laws definitely didn’t exist back then. For all the kind of bits of things and writing and whatever we did with him, he could never pay. There was never any money around. But he would pay you in-kind. One of the things he did, he produced a ream of paper that he sort of slapped down on the table, and it was his mailing list. It was amazing. I’m sure the same versions of this mailing list were passing hands around varying young artists in London.

IF: The story goes that he’d actually originally stolen it from Anthony d’Offay, when he worked as an art handler in the d’Offay Gallery, when he was a student at The Courtauld [Institute of Art]. This mailing list was the sort of springboard to launching Words & Pictures, and that’s why he gave it to us. Again, it was just much harder to access information at that point, and suddenly having this document enabled us to contact the great and the good of the London and the global art world, and was a remarkable gift.

BL: So there’s another person I want to talk about with you, someone who you’ve had a lot of connection with over the years, and that’s Nick Cave, the very iconic singer songwriter. You’ve collaborated several times, including your great, first feature length film, 20,000 Days on Earth from 2014. I’d love to know what you learned from Nick Cave.

JP: Nick is incredibly impressive. And in a way, he also embodies something of that delicious mixture of the absolutely accessible and the kind of ambitiously philosophical or mythological, in a way. And there’s some of that to his Australian-ness, I’m sure. But there’s something of that loftiness. And then that utter debased humor, down to earth-ness. That combination in anybody is absolutely intoxicating. Definitely we were really attracted to that in Nick.

And I think in a way now, almost all of our thinking and our practice kind of owes something to Nick and owes something to the huge transformation that happened to us whilst we were making 20,000 Days on Earth, where we found that we were able to take ideas that we had been grappling with from way back, from those days in Goldsmiths, and somehow find the mode of being able to explore them and to articulate them and to resolve them, in some cases, in the language of film, which I’d never guessed that we could do. Nick makes you feel like almost anything’s possible.

20,000 Days on Earth. 2014. Film (97 min.) with Nick Cave

DIRECTOR: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard

WRITERS: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard and Nick Cave

PRODUCERS: James Wilson and Dan Bowen

Copyright: Pulse Films and JW Films with support from Film4, BFI and Corniche Pictures

Photo: Amelia Troubridge

Courtesy the artists and Pulse Films

IF: Yeah. He’s a great advocate. There are things that we did at the request of Nick, with no formal or even informal kind of qualification to do whatsoever. The one that always stands out to me was when he wrote his last novel, The Death of Bunny Munro, and did a reading tour where he went on the road and did book readings and played a few songs with a stripped-down band. Nick asked us to come on the tour and do the lighting and the stage show for that tour.

Now that’s not something we’ve done. It’s not something we know how to do, but Nick just had this idea that we’d be good at it. We’d be capable of it and he trusted us. I think for somebody in a position to pretty much pick and choose who he wants to work with and to say to you, “No. You’ll be fine. Just give it a go. It’ll be great.” This was just a remarkable amount of trust and confidence to give to someone.

JP: I think the biggest gift or the biggest influence that Nick has had on us is us beginning to understand what it was we didn’t like about a lot of the work being made around cultural figures or musicians or artists. There’s this kind of sammy [half cooked] journalistic, quasi-observational tendency to try and strip away the mythology of the person. And then at the same time, somehow over mythologize their art or their practice.

So, you’re seeing the person doing their shopping or cooking their dinner, like a normal person. And then there’s a sort of smoke and mirrors kind of confusion or cloud around the work that they’re doing, the art that they’re making. I don’t know the point that it clicked, when we understood that to be interesting, you need to turn that on its head and actually work with the mythology of the person that they’ve already started to kind of create in the way they look, in their lyrics and their language, in their moves. You work with that, you enhance that, you build upon that. And then you strip away the mythology around the art.

Because truth is, anybody can make something. Everybody can do some kind of artistic act. You just actually have to bother seeing it through. Find a good idea, develop it, question it, work with it. And it is kind of 99% effort. I think across the kind of set of projects that we have on the go at the moment, there’s something of that ethos that is now in play in all of them.

BL: So let’s move on to how you collaborate. With collaborators, you have to externalize things. It has to be spoken about. Do you think of the creative process and collaboration as a real workable thing?

IF: It’s the process by which stuff gets done. It’s the process by which you stop yourself digging into those interminable, internal cycles of doubt and self-confidence and lack of self-confidence. I think for me, I feel like I would just be lost. I think through working collaboratively together for such a long time has enabled us, and perhaps has taught us how to collaborate well with others. Over the years, I think our work has had this sort of expanding pallet of collaborators, for the want of a better word. 20,000 Days on Earth was probably the kind of the peak of that particular mountain, in the sense that a feature length film takes a lot of collaboration. It takes a big army of people to get it done. You can’t really be the sole artistic genius in the middle of it, or it ain’t ever going to happen.

JP: It’s never been easy though. I think we probably collaborate more effectively with other people than I often feel we do with each other. I think as we live together and we’ve built our life around our work and around our togetherness, it isn’t the kind of excessive, constant bubbling hive of creativity. It’s an elusive slippery battle with something you just don’t understand. And some conditions help. We can go through phases of, “If we go out for a walk every day, you just find yourself talking and that seems to really help.” But it never stays that way. It’s constantly trying to somehow evade you. Maybe that’s what keeps it interesting, in some ways, is that it isn’t easy.

IF: I think the fact that it’s hard won is what makes you able to be confident in it when it is working, because those checks and balances have kind of already been run between the two of you. I guess that’s what I mean about now not really knowing how I would operate on my own as a single creative entity, because I think I would still be looking for that dialogue, that conversation from someone even if it wasn’t directly a creative collaborator, if it was only just phoning a mate or something. I think I would still need that ability to externalize, to verbalize.

JP: It’s maybe because your opinions and even your instincts are not formed in a vacuum. They don’t come out of you fully honed. For most people, they’re a constant kind of work in progress depending on what you’re reading, depending on the people around you and their opinions. I think it’s that sense that when they align, when both of our instincts, both of our kind of opinions on something feel like they get into a groove with each other, then you know it’s really rewarding. Because then you kind of know you’re onto something, you know that and you can move in quick. I think we really enjoy that it enables us to make really quick decisions because it’s as simple as, “Do we both feel that or not?” And if we both feel it, you follow those feelings.

BL: It seems that Samuel Beckett became your most enduring inspiration. His Not I from 1972 performed by Billie Whitelaw is something you often return to. Do you want to tell me about that?

JP: I would add Lindsay Anderson, too. It’s the same thing that I love in both of them. It’s that the real kind of singular ambition, a voice of idea and how often it fails because it’s so kind of big. But in encountering it in watching Anderson’s films or in experiencing Beckett’s plays, you can’t help but sort of be in awe of that ambition, in awe of their sort of visionary-ness or the epic-ness of what they’re attempting, gets you every time.

JP: I think Beckett is also the closest you get to installation work on the stage, the thinking that it is a state that you’re invited to exist within for a period of time. And to me that kind of defines what installation art is. I find the language of installation that I really love is the same language I find in Beckett. That notion that it just happens to also have actors, people embodying kind of elements and ideas in it, makes it all the stronger.

BL: Music continues to play a very big part in your life and your work, especially music from 1973, which is around the time you were born. The groups include the New York Dolls, Lou Reed, John Cale, the Sewages, David Bowie. You’ve said that music is time travel and a few notes are all it takes to derail the conscious mind and let the past come flooding through. What is it about music that keeps you returning to it?

IF: 1973 was one of those weird, almost magical ciphers that just somehow keeps returning in most of the projects we end up doing. I don’t quite know what it is that 1973 seems to have… But you can almost second guess, if there’s something we’ve unearthed somewhere, some piece of research we’re doing, at some point some 1973-related significance will somehow pop out of the woodwork.

JP: I’ve never tried to articulate this before. Going back to when we were at Goldsmiths and that connection between wanting to make art that somehow had the relationship with the audience that we were witnessing in independent music, we understood absolutely in a sort of theoretical way in the power of music or in what it was making possible. We had an amazing set of tutors. Sarat Maharaj was notably one of the ones who really changed us, in his teachings on James Joyce and Richard Hamilton and Duchamp, and really kind of opened us up. Before this, we both didn’t know that we picked the wrong course at Goldsmiths. Goldsmiths has an art department, which has this kind of smaller course, which is art and art theory. Then it has the bigger course, which is just art practice.

There was a difference between these. I just thought, well, of course you want to try and you want to look at the kind of theory of art at the same time as you’re making it, that’s the right course to take. A lot of our kind of anger and frustration came from being on the underdog course, the course that was kept in a kind of dirty old mechanic’s garage across the road, whilst the kind of main art course was housed in the great Goldsmiths building. We were always fighting some kind of small battle to be heard or to be kind of taken as seriously as [students in] the other course. But I think that in being asked to read and think and write around not just your own practice, but around other people’s practices and other thinkers, it really helped to begin to kind of look at those things that you understand instinctively to be able to unpick them.

We wrote a piece way back then about music. We wrote about the iPod, and the Shuffle, which was totally new to the market and was being advertised absolutely everywhere. We were fascinated by how this little thing that you hung around your neck and had loaded up with all your favorite tunes. What impact the random shuffle thing would have on you? You’re no longer listening to these almost curated albums or these kind of toiled-over mix tapes that somebody made for you. You know the way a song ends and you’re preempting the next song.

But somehow this kind of weird, fatalistic, in the lap of the gods small bit of plastic was just randomly pulling up something and kind of pushing it into your ears. We wrote a lot about this idea of how that might really derail your consciousness or how it might prompt a form of time and space travel, because of the associations connected to some of those songs. And how that could almost happen in a sort of spontaneous way, in a way that you had no control over because of the music being kind of randomly punched at you.

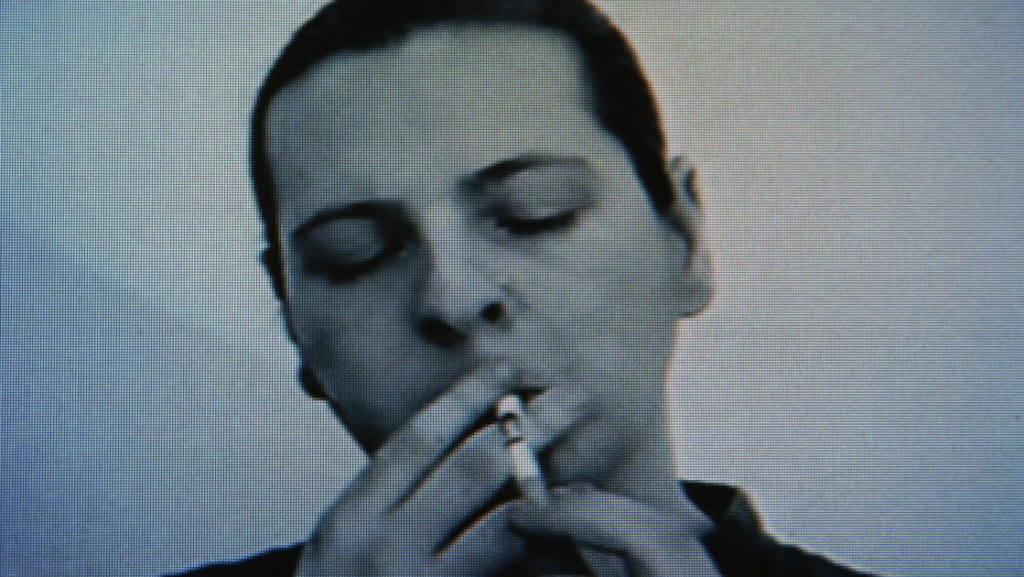

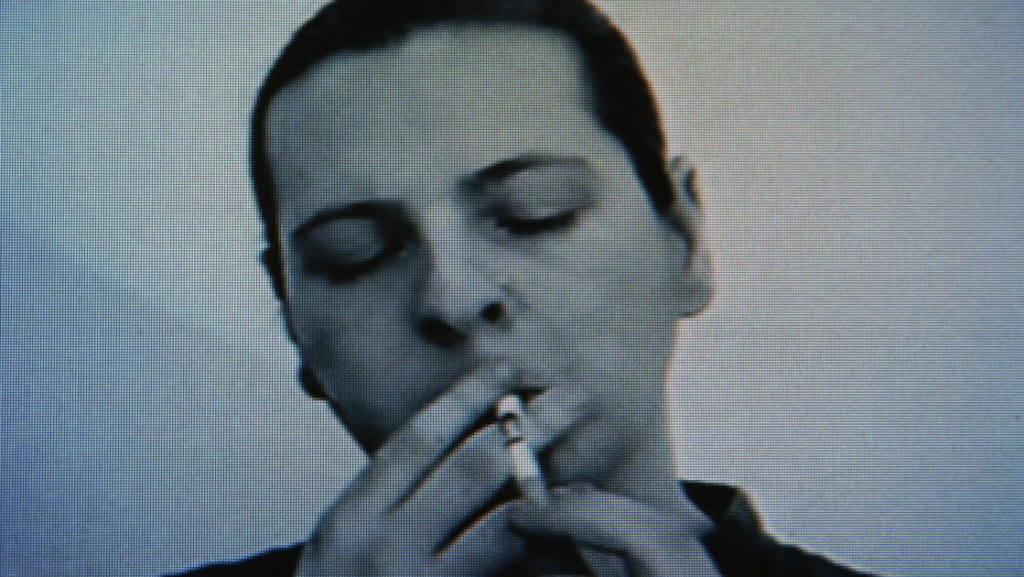

BL: That leads right into the next question. Your very first video is Chain Smoker – Tap Dancer from 1995.

Photo: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard

Courtesy the artists and Kate MacGarry, London

Photo: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard

Courtesy the artists and Kate MacGarry, London

It’s a two-monitor installation with a pair of unedited single take videos of nonstop actions that each of you perform. The top monitor features a single shot of Iain’s head presented actual size as he chain-smokes. The second monitor placed at foot level features a single shot of Jane’s feet wearing tap shoes and tap dancing. Iain doesn’t speak or make a sound, but Jane’s tap dancing is the only sound of the piece. Was this about self-portraiture?

IF: I guess it was about two things. On the one hand, it was about looking at our experiences prior to meeting each other and trying to sort of offer up something of a hint of what that life perhaps was. And on the other hand, I think something that we only really came to understand properly in retrospect was that we were, in our own way, going on a very similar journey that a lot of artists of a much earlier generation had been through as the consumer technology to video record had become available. We found ourselves at Goldsmiths at a time when video technology was relatively affordable, although not really affordable to you as a student. It was kind of still unlikely you could go out and buy a camera. But the college had a store of equipment you could go and book to take out and experiment with.

We had access to these, probably VHS cameras that we could play with. We would find ourselves booking a room and booking a camera and just playing, just experimenting. Of course, with the glorious benefit of hindsight, you realize that’s exactly what people were doing with early portapacks and all sorts of various technology over the years. But I guess it also goes back to that idea of something that feels quite formal and quite presented, feels like video art in some sense but is also pricked with that kind of humor of the sort of ludicrousness of these repetitive actions.

I think there’s something about humor, as well, that has always been really important to us. I think something that particularly appeals to me is people that can almost smuggle humor into works that perhaps on the surface feel quite serious or feel quite epic or feel quite important in some way yet somehow within that, there’s still a sort of just a little needle poking at something. And I think there’s always been that desire to marry that sort of serious intent with an undermining.

JP: Quite a few recurring motifs in our practice, I think, we were kind of solidified in the making of that piece. The use of “real time” single take, that performance to camera, the power of understanding there is no trick in the edit. This entity inside this monitor exists in the same time as you the viewer, and in a way as just an extension of the space that you’re in. So, the boxing and the ability to have real sized head, real sized feet, they’re things we’ve always gone back to. They’re things that are there in everything.

And maybe it just is that simple urge. If you want to be able to connect with your viewer on a visceral immediate level, that being in the same kind of time zone, being in an extension of their space and being the same size as them, that somehow gives you something in common immediately, it gives you a kind of way of understanding something immediately. We had to do the smoking one first because we weren’t sure how many cigarettes he was going to manage to smoke. I knew I could tap dance for as long as needed, but it was interesting. Because we had to do the smoking one first and then a sort of rather sick gray looking Iain had to film the tap dancing one.

IF: It was kind of the joke that was there before we’d met. Jane had studied at stage school [theater school], and perhaps in a parallel universe is somewhere right now dancing on a stage somewhere. That’s a life she may have had. Whereas, I was standing around some dirty venue somewhere watching a crappy rock and roll band and smoking cigarettes. So that was kind of the gag.

BL: The notion of the video camera becoming a co-conspirator or a third silent collaborator. Do you think about that?

JP: I think we’d seen that. Actually, for us, the first encounter with that was Gilbert & George’s work with the still camera, perhaps way before we got to know the work of Acconci or Nauman, and really sort of witness exactly what we’d been through in their work but not Gilbert & George. I think that idea of the kind of double act, as well. I mean, I don’t think that we would ever have considered working together, had it not have been for Gilbert & George. I think they showed us a template that made that feasible. Because the only other collaborators we knew at the time were all siblings. We were tutored by Jane and Louise Wilson, only ever one at a time, because the school would only pay them one fee.

So, we’d have week on week off, Jane or Louise. And we knew Jake Chapman, the Chapman Brothers through Joshua. So, I think we maybe thought that you had to be related to collaborate, or that somehow would add to it. But of course, in comedy you see the kind of Morecambe and Wise [an iconic English comic double act] and Laurel and Hardy. There was something of that kind of humor in Gilbert & George, as well. I think there’s no way we’d have even known to collaborate, had it not been for them.

BL: So another topic I thought we could touch on, which is the history of technology, which is of interest to you. That topic is at the heart of your work I selected for the exhibition “Seeing Sound,” Requiem for 114 Radios.

Photo: Paul Heartfield

Courtesy the artists and Kate MacGarry, London

It’s a loop-sound installation with mixed media, including filing cabinets, a tinkerer’s workbench, electronic apparatus, and 114 analog radios scattered around the room. I love how the installation appears to be an anonymous archive with the abandoned workshop of a radio enthusiast. Each radio frequency is playing a vocalist singing a different dramatic version of Dies irae from the Roman Catholic Requiem mass for the dead.

Dies irae was interpreted by such composers as Verdi and Mozart and used to very chilling effect by Stanley Kubrick in his films A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. To me, Requiem for 114 Radios is a testament to the death of analog technology, as the radio’s call upon a universe of mysterious messages, modulated hisses, mangled voices, incomprehensible words. What were you thinking about when you made the work?

JP: It’s almost technology come full circle. When radio was first invented, there was discussion, there was the possibility that one might pick up a voice from the ether that one might be able to hear the communications of the dead somehow lost within these airwaves. And it feels like the technology has kind of been through sort of functional mainstream safe space and is now returning back to that original space of feeling somehow liminal, a feeling that it might be capable of something kind of supernatural or extraordinary in some way.

IF: Or extraterrestrial.

JP: Yeah.

IF: I mean it’s kind of incredible, the radio waves. The kind of the thing that we expect will be the way that we’ll receive communication from out there, this idea that radio, which feels like such an out of date, such an analog faded technology, could be the thing that potentially shepherds the kind of greatest leap of human understanding is kind of amazing.

And I think radio is associated with authority of some sort, that somehow the right to broadcast brings with it a kind of an authority in the voice of that, that might be how you learn about war or how you find out the truth. Even now, if something is kind of sparking off on Twitter, I’m turning the radio on. I want to know what the BBC are saying. There’s this still this sort of a distrust of the ability for internet kind of digital technology to somehow be, as we’ve seen in the last few years of politics, to be heavily manipulated and manipulative, and that you’re looking for a truth beyond that. I think radio brings with it an idea of truth. The idea was such a simple one. The number 114 came from Kubrick. We just knew we needed a kind of a number that you couldn’t count, a number that was like a big choir. And we found the 114 in Kubrick’s work.

We knew we couldn’t approach 114 people, but we knew we could approach fourteen singers to all perform the same piece. I love it. It’s oddly, one of the only pieces that I think we’ve made that I really enjoy being inside, and I really love it. Because it’s affected by the body as well, because there are fourteen transmitters and 114 radios picking up on fourteen live, FM kind of locally broadcast signals that as you move around the room, and as your heat and your own kind of static electricity kind of shifts around the space, it kind of plays into the piece, the radios crackle. I don’t know, there’s something really lovely about it.

IF: It’s an unpredictability, isn’t it. I think that’s probably something that keeps drawing us back to these kinds of technologies, like radio, like analog tape, like live performance. These are all sort of situations where at some point you relinquish control to something greater than you, outside of you. And your own sphere of control is suddenly kind of broken by these things like FM transmission or analog tape or a performer on a stage that isn’t you.

And I think that takes us right back to this idea of the relationship with music. Again, one of the great joys of music performed live and the live music experience is that it is unpredictable. It has the potential to be something other than the simulation of the live recording. Nobody wants to go to see a live show to hear something that sounds exactly like the record you could have played at home. You’re going to see something that is slightly different, slightly unpredictable.

JP: …to sharing something, or to feel something beyond what’s able to be captured on a slab of vinyl. I think that’s very true of radio. Of course, what we also have is the whole cultural history of the radio, as well. The way that it has kind of played out in horror films, that’s loaned to the use of it now that we’re able to use… a lot of sort of supernatural films, I can think of that have kind of voices that are coming through on a radio or where the kind of signal is weak but it’s somehow kind of haunted. They come with a lot of baggage, a lot of good baggage.

BL: You’ve worked with many different organizations, private, public institutions, commercial galleries and film distributors. How do you separate the art and the cinema, or do you?

IF: Honestly, I think we don’t. But I think the industries themselves kind of create a fairly natural and unavoidable division just through very practical concerns. I think in our heads, it’s all part of the same practice. Someone asked us the other day whether we thought of ourselves as artists or filmmakers or artist filmmakers. And our answers were different actually. My answer was that I still and always have thought of us as artists because to me, the attraction of art school, in a way all those years ago, was that artist seems to be that sort of magic word that allows you to spin in any direction. There isn’t a door closed as an artist. It feels like the moment you attach any other definition, to be a filmmaker, you shouldn’t really be dabbling in sound installations because that’s the job of someone else. Whereas artist feels like the key that unlocks all the doors.

JP: I think there are kind of modes of operating that we’ve definitely brought back to our art from our experience of working with film production companies and distributors and execs and sales agents and stuff, where even as a kind of auteur director, you’re still not. You’re not completely sort of trusted if you like to fully kind of conceive and deliver every last detail of something in the way that you would be as an artist, that you are the one, and only you that kind of does that. It’s been really useful. I mean, I’ve loved it. I really thrived and maybe it won’t be the same on film number two, but I really thrived on 20,000 Days…

We were sitting around with really incredible intelligent women exec producers, who were all hungry to kind of input ideas but they weren’t pushing any of them. They weren’t saying, “It has to be this way.” They were just asking questions. “What happens if you do this? Why aren’t you captioning when we’re moving from the studio in France to the psychoanalyst interview?” Do we need to understand that these are in different places or in different timeframes? And just even having somebody kind of pose that question, it helps you to kind of understand your own stance on it.

For us, it wasn’t immediately like, “Well, no, it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter to the audience that…” Because in a way, Nick’s the one that’s kind of taking you through both of these spaces and you just have to trust in him, and we don’t need to label that. Nor do we need to acknowledge the surface of the screen. That in itself putting type onto the surface of the screen kind of reminds our viewer that they’re watching a flat representation of something, an illusion and not real thing. Whereas whilst we can play with durational time, extension of space and somehow kind of real-life size in some way, then you can be lost to that a little bit. You can kind of slip into a world where you’re completely kind of absorbed in what you’re watching.

IF: And that is sort of relationships that I guess we’ve never really had in the art world. I don’t know if other artists would feel the same or, perhaps, they have a different sort of feedback loop that creates that for them. But I think our experience has very much been that within the art world, it’s really once you’ve completed a project and you sort of present it to the world that suddenly normally there’s a whole queue of people willing to tell you what you’ve done, what you’ve done wrong, what you should have done, and so on. That’s the point where you get public feedback, you get perhaps press and journalists telling you what you should have done differently, or what they think of what you were trying to do.

But to have that sort of formalized within the creative process, where there are these stages where you as a group of people will review work, will discuss work, will discuss ideas, will collaborate. I think it was really unusual for us and a really valuable process that I think we’re now trying to find ways to replicate within the rest of our practice.

JP: I can really understand how in certain areas of the history of our practice, there have been incredibly influential sort of creative producers. I think we now acknowledge that we really thrive with that relationship. The producer that we worked with on 20,000 Days.., he’s key to the way in which we shape and sort of place how we’re doing what we do. But we have had some interesting relationships in our art practice. There was Vivienne Gaskin at the ICA, who commissioned a lot of the early performance work. I now realize that we were really collaborating. There was that sense that the kind of together, the sort of bounce between us. It was sort of that we should kind of operate it like a creative producer.

There was Elisabetta Fabrizi who opened the BFI gallery when it briefly had this kind of incredible space for experimentation. And again, I feel like with her, we operated in a different way. There was more a kind of back and forth. And then we have some of those relationships in some of our regular collaborators, whether they’re actors or Raj Patel, who’s in the New York office of Arup and has been involved in so much of our work. And again, kind of where he sits maybe you’d call him a kind of technological consultant or an acoustics consultant to our practice. But it’s much more than that, because we bounce off him all the time the kind of ideas, but what if? But how could? Reverse that! And it’s such a sort of creative relationship.

BL: What’s next for you?

JP: Who knows? Who knows? This situation is so strange. The year we thought we were going to have was to be filled with incredible exciting projects, but is not the year that I think we’re now going to have. Over the last couple of weeks, some really interesting kind of possibilities of “rear the head.” I think over the last few years, the one thing that we have been really kind of aware of is that you never quite know when the conditions, the sort of aligning of conditions is going to be right for one project to really pick up. And that’s definitely come with the sort of straddling of two industries. I think if we were just operating in the art world, that’s where you can have a lot more control. Whereas the moment you’re trying to kind of straddle into television and online media and particularly film, you lose a lot of that control because it’s attached to money.

IF: For the greatest part of this year we’d been working on co-curating an exhibition that was due to open at Somerset House in September, which is now sadly postponed due to the pandemic.

Photo: Tim Bowditch

Courtesy the artists and Somerset House, London

That got put on hold and, weirdly, we were also kind of involved in another exhibition that has been put on hold, which was a Nick Cave exhibition in Copenhagen. We had assisted in two rooms of the exhibition. One of them is a recreation of the office that appears in our film, which itself was a kind of reimagining of what Nick Cave’s office perhaps should look like. Just before lockdown here, we were in Copenhagen dressing and creating a fake office for Nick Cave in a gallery.

JP: I know what I want to happen next. I want to make another film. We’re having a lot of ideas that straddle the kind of world that’s now called hybrid documentary. But for us it’s always just that lovely slippery area between sort of true and false, authentic and inauthentic.

BL: My very last question, which I think you’ve already kind of answered, is the question I’m asking everybody I speak with in this series. Do you consider yourselves media artists?

JP: Don’t mind you considering us media artists.

IF: I guess for me, again, the word media feels like it closes some other doors. I maintain this idea that artist is the skeleton key that opens all the doors. I would consider media art part of our practice. I would still consider us to be artists able to open all the doors, not necessarily successfully but at least allowed to try.

BL: Well, I think you opened lots of doors and you’ve opened many doors for me because I’ve so enjoyed every time I talk with you, whether that was the very first time at the BFI when you presented your installation there, and then over the years. I hope we can get together in the same room, some place soon.

JP: We’d love that.

BL: Thank you.

JP: Thank you.

IF: Thank you.

BL: On behalf of Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, thanks for joining me for this episode of Barbara London Calling.

—

This conversation was recorded June 26, 2020; it has been edited for length and clarity.

Support for Barbara London Calling is generously provided by Bobbie Foshay and Independent Curators International in conjunction with their upcoming exhibition, “Seeing Sound,” curated by Barbara London.

Be sure to like and subscribe to Barbara London Calling so you can keep up with all the latest episodes. Follow us on Instagram @Barbara_London_Calling and check out BarbaraLondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Bower Blue , with lead producer Ryan Leahey and audio engineer Amar Ibrahim. Special thanks to Le Tigre for graciously providing our music.

Images & Video

Iain Forsyth (b. Manchester, 1973) and Jane Pollard (b. Newcastle, 1972) are London-based artist-collaborators with a background in installation art and the moving image, with a keen interest in music and sound. Their collaborative practice began at Goldsmiths College, where they studied fine art and art theory. Their first collaborative project was Words & Pictures, an art magazine in a box with objects made by 20 different artists, published between 1994 and 1997.

Photo: Courtesy the artists

The publication was born out of Forsyth and Pollard’s interest in fanzines, punk and underground publishing. The project was a cross-breed; part magazine, part exhibition and part book.

Their fascination with the history of technology is at the heart of Requiem for 114 Radios (2016), a looped sound installation with 114 working analogue radios. The installation appears to be an anonymous archive, or the abandoned workshop of a radio enthusiast. It is featured in “Seeing Sound,” an exhibition circulated by Independent Curators (ICI), 2021-2024.

Music plays a central role in Forsyth and Pollard’s award-winning debut feature film, 20,000 Days on Earth (2014), a musical documentary drama about the singer, songwriter, author, screenwriter Nick Cave. Previously they collaborated with musician Scott Walker on Bish Bosh Ambisymphonic (2013), an ambisonic sound installation.

In 2010 they directed Gil Scott-Heron’s final video.

Most recently they directed an unusual music video with Jarvis Cocker’s new band, Jarvis Is, performing in a cave.

Cinematographer: Erik Wilson.

Photo: Courtesy the artists and Rough Trade

Photo: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard

Courtesy the artists and Kate MacGarry, London

Photo: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard

Courtesy the artists and Kate MacGarry, London

The two-monitor installation consists of a pair of unedited, single-take videos depicting nonstop actions that each artist performed. The top monitor features a single-shot of Forsyth’s head presented actual size, as he chain-smokes. The second monitor, placed at foot level, features a single-take, single-shot of Pollard’s feet wearing tap shoes and tap-dancing. He doesn’t speak or make a sound; the beat of her tap dancing is the only sound in the work.

The artists teamed up with Scott Walker to create a unique, immersive sonic re-imagining of the musician’s recent album, “Bish Bosch.” Walker allowed his archive of recordings to be taken further with four tracks from the albums “Pilgrim,” “Epizootics!,” “Tar” & “Dimple” mixed and spatialized into an ambisonic symphony. The resulting piece presents Walker’s world of depth and originality, plunging the listener into near darkness.

20,000 Days on Earth. 2014. Film (97 min.) with Nick Cave

DIRECTORS: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard

WRITERS: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard and Nick Cave

PRODUCERS: James Wilson and Dan Bowen

Copyright: Pulse Films and JW Films with support from Film4, BFI and Corniche Pictures

Photo: Amelia Troubridge

Courtesy the artists and Pulse Films

The film portrays a fictitious 24-hour period in the life of the musician, songwriter, author, screenwriter, composer and actor Nick Cave, prior to and during the recording of his 2013 album Push the Sky Away. The film and its title were inspired by a calculation Cave made in his songwriting notebook about his time on Earth. The verité observation of Cave’s creative cycle probes his artistic process and celebrates creativity. Toward the end of the film, Cave describes living in the “shimmering space” where imagination and reality intersect.

Photo: Paul Heartfield

Courtesy the artists and Kate MacGarry, London

The mixed-media, looped sound installation includes filing cabinets, a tinker’s workbench, electronic apparatuses, and 114 working analogue radios scattered across the space. The installation appears to be an anonymous archive, or the abandoned workshop of a radio enthusiast. Each radio features a vocalist singing a dramatic new version of “Dies Irae” from the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass. (“Dies Irae” was famously interpreted by such composers as Verdi and Mozart, and was used to chilling effect by Stanley Kubrick in A Clockwork Orange and The Shining.) Requiem for 114 Radios is a testament to the death of analogue technology, as the radios call upon a universe of mysterious messages, modulated hisses, mangled voices and incomprehensible words.

Somnoproxy (Online version) from Iain & Jane on Vimeo.

Photo: Tim Bowditch

Courtesy the artists and Somerset House, London

The installation incorporates a futuristic bedtime story about a conman who offers his services to sleep on behalf of wealthy executives who are too busy and too stressed to sleep themselves. To experience the work, viewers are invited to lie down in a personal auditorium called “The Island,” designed by L-Acoustics Creations. Concealed within the Island is cutting-edge technology built on a proprietary 24-channel audio system, capable of faithfully reproducing a full 140dB dynamic range, extending into the infra-low range. In front of The Island stands the “Dream Machine,” a stroboscopic flicker device designed by Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs, with Ian Sommerville. The device rotates allowing light to be transmitted at between 8 and 13 pulses per second, a frequency range that corresponds to alpha waves, electrical oscillations present in the relaxed human brain. Dream Machine purportedly can induce a hypnagogic state.

Written by Stuart Evers, the narrative is read by actors Enzo Clienti and Kate Ashfield, with a sonic accompaniment created by Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard in the Moog Sound Lab UK.

Jarv Is… Live from the Centre of the Earth. 2020

Cinematographer: Erik Wilson.

Photo: Courtesy the artists and Rough Trade

Jarvis Cocker, founder of the 1990s band Pulp, was scheduled to tour the U.K. with his new band, Jarv Is, when the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown made live shows impossible. Instead, the band went ahead and set up their equipment in a cave in the Peak District, Derbyshire. They played their new album Beyond the Pale in its entirety live, without an audience. Forsyth and Pollard directed the unusual virtual concert film, which was streamed free on YouTube for 24 hours in July and will tour UK music venues in November.