Barbara London: My guest today is Marco Fusinato, the Australian artist and musician whose work explores noise and duration. As a musician, his approach is conceptual rather than technical. Born in 1964 in Melbourne, Marco released his first solo record in the ’90s. He has said he uses the guitar as a signal generator, and uses amplifiers as an instrument creating improvised noise guitar performance that can run for hours, days, even months. His work has been shown across the world, including the 2022 Venice Biennale in the Australian Pavilion. We first met in Melbourne about 15 years ago when I had a residency at the Gertrude Contemporary Studio. As soon as I arrived, I knew I had to meet you. Marco, thank you for joining me.

Marco Fusinato: Hi, Barbara. Nice to be here.

Barbara London: What was your first job?

Marco Fusinato: I grew up in a part of Melbourne that was working class with lots of migrants. My parents had migrated from Italy. Migrants were factory fodder. It was heavy industry in that area. Back in the day, there were telephone books that were large, heavy tomes, and each one probably weighed two to three kilograms. The job I got was in a factory. When I turned up at 7:00 AM, the foreman said to me, “Here’s some earmuffs. Here’s some gloves. Stand there.”

There was a conveyor belt. Four of these phone books would arrive at one time, wrapped in shrink wrap and I’d have to pick them up and put them on a pallet. As the pallet grew, the more difficult it was to lift these books. Then a forklift would come and take them away. You’d do one pallet, but the machine doesn’t stop. Then, you do another pallet and another pallet. By lunchtime, I was so exhausted. About the fourth day, I went up to the foreman and I said, “I can’t do this anymore.” He just laughed and replied, “I’m surprised you lasted this long. Most people leave after the first day.” So that was my first job.

Barbara London: My next question is, what was your introduction to the creative experimental community and to music in Melbourne? Melbourne has quite lively scenes, including music. You have many music colleagues, and many visual art colleagues, and your practice grew out of these two communities. You’ve played the electric guitar for a very, very long time.

Marco Fusinato: In the early ’90s, most of the art being shown in commercial galleries and institutions was expressionist painting. But I was involved with an artist run space called Store Five, which at the time was the only artist run space in Melbourne. Its focus was on conceptual art, and this was the area I was really interested in. I met artists that I would go on and be associated with.

The gallery was a very small space situated down a back lane. Its program was very, very focused and rigorous. For a period of time I had a studio above the gallery and met many artists that I was interested in and shared common interests. The gallery folded sometime in the mid-’90s. Around the same time I was a record collector, and would frequent record stores. One day, I walked into a record store and to my surprise discovered many obscure experimental records that I never seen in that store before.

I selected some, took them up to the counter, and the guy behind the counter looked up and said, “If you want to buy those records cheaper, I will meet you outside after work,” which I did. He was running a mail order business and soon we became friends. Shortly after, he opened a store in exactly the same space, in the same building where Store Five was all those years before. So here I was many years later, going down the same lane, but this time meeting and performing and recording with experimental musicians and musicians that I would then go on to be associated with.

Barbara London: Was it around that time that you became interested in the electric guitar?

Marco Fusinato: I’d been interested in the electric guitar since childhood. I think it’s the popular instrument that defines my lifetime, and I’d always enjoyed its cultural status and tried to make sense of it. I liked the sound of it. Also, the first music I really got into was fueled by the electric guitar, and that was that first wave of punk rock. I found it exciting.

The main reason I found it exciting, apart from the music of some of those bands, was the interviews they gave. Because in those interviews, the musicians didn’t speak about Baby, Baby, Baby and technical proficiency or fast cars. They spoke about social change and so on. In some of the interviews, they would mention things like Marxism or anarchism or terrorism or situationism. So, I would want to know more.

It was a way of discovering these things through those interviews. I would go and try to find information about what they were referring to. And so, it wasn’t just the music that was important. Back in those days, it seemed like it wasn’t possible just to learn and play the guitar. There wasn’t the information around, although I was really interested in it. It was always something that was there. And it was only later through understanding conceptual art that I could apply ideas to the instrument in my own way.

I never had the kind of patience or the ear or the technical ability to learn the guitar in a traditional way. I didn’t want to, either. I remember going into those guitar stores and they would be full of books on how to play in the style of so-and-so. I thought, “There’s no section here on how not to play in that style.” And maybe, that is interesting to embrace your own limitations and try and create your own language, the same way that conceptual art offered that possibility.

Barbara London: Marco, you were telling me too that sometimes you would go into a guitar store as if to buy and try out an instrument. But you would then play and rehearse or even record?

Marco Fusinato: There was a series I made in the ’90s when there was a new invention. It was called the MiniDisc recorder, which was this tiny little digital recorder that could fit in a pocket. I bought one when it first came out. I was traveling a lot then for exhibitions, so I was traveling without music gear. I had the idea to use the music store as a ready-made recording studio. So, when I was traveling, I would seek out a guitar store. I would have the recorder in my pocket, and would walk in and ask to try a distortion pedal.

That way, they would have to give me a guitar and an amplifier to try it. I would turn everything up and just make extreme noise in their store. In order to do it, I really had to work myself up and get myself in a zone, because it’s confrontational and I didn’t know which way it would go. I did it all around the world and so, it became a series. This is way before mobile phones and so on.

I would do the recording, leave the store, and with the camera I had would take a photo of the shopfront. I then released most of those in 7-inch records. Each situation was quite different. It would depend a lot on who was working in the store, where they would set me up, and that would determine how kind of antagonistic it would be.

There was one we videotaped. I was with someone who had one of those big video cameras, which he hid under his coat and we filmed it. It’s always awkward at the end of those interventions to give the guitar back to the shop assistant and say, “Uh-huh. No thanks,” and there’s total confusion in the store as to, “What the fuck was that?” It did its time and I kind of stopped that in the early 2000s.

Barbara London: That’s a little related to something that you once said, which is there’s no difference between doing the soundcheck and playing the set in the performance. You prefer to harness the energy it takes to be there, to be fully present and occupy the performance space. So how do you distinguish between the soundcheck and the set? Or maybe there isn’t a distinction.

Marco Fusinato: Well, I think you can imagine, I set up the equipment, make sure it’s all working, and then in that process, I’m improvising. I feel like, “Oh, can I just keep going now because this is it?” This became frustrating that a soundcheck might happen at 4:00 PM or 5:00 PM, 6:00 PM and then you don’t go on stage until 10:00 PM. So, there are these three or four hours of just waiting around, which was frustrating.

Spectral Arrows

Melbourne Performance

2018

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

That frustration and also the frustration of traveling, for example, from Australia to Europe or America or whatever. It’s a 24-hour flight, then you check into a hotel, then you go to the venue, then you get on stage and you perform for 30, 40 minutes. It just seemed perverse to me and ridiculous. Through that frustration, I invented a project called Spectral Arrows, which is this project where I would turn up and perform for the time the gallery, museum, theater, whatever was open.

It would usually be from 10:00 AM until 6:00 PM. And that way, I could really explore the sound and what I was doing and allow it, the sound, to take me into unimagined places. Whereas, a 30-minute set on a stage felt like there was always more to explore. The other thing is these kind of improvisations, for example when they’re done in a club context, a 30-minute set or whatever, no matter how fucked up the sound is, there’s still this architecture there which tells listeners they’re there to be entertained. There’s a stage, the performer faces the audience, the audience looks at the performer, so there’s a contract.

Whereas, with Spectral Arrows, it really changed things for me because the way it was set up was that I would face the wall to avoid any distractions when I played all day in the gallery, museum, or theater. I could just really focus on the sound, and the audience members were free to come and go as they pleased. So, some people would come for a few seconds, others would stay all day. They were free to roam the gallery space and experience the work from wherever they wanted. So, in a way, they were on stage with me and with all the equipment. It just felt a lot freer and more all-encompassing.

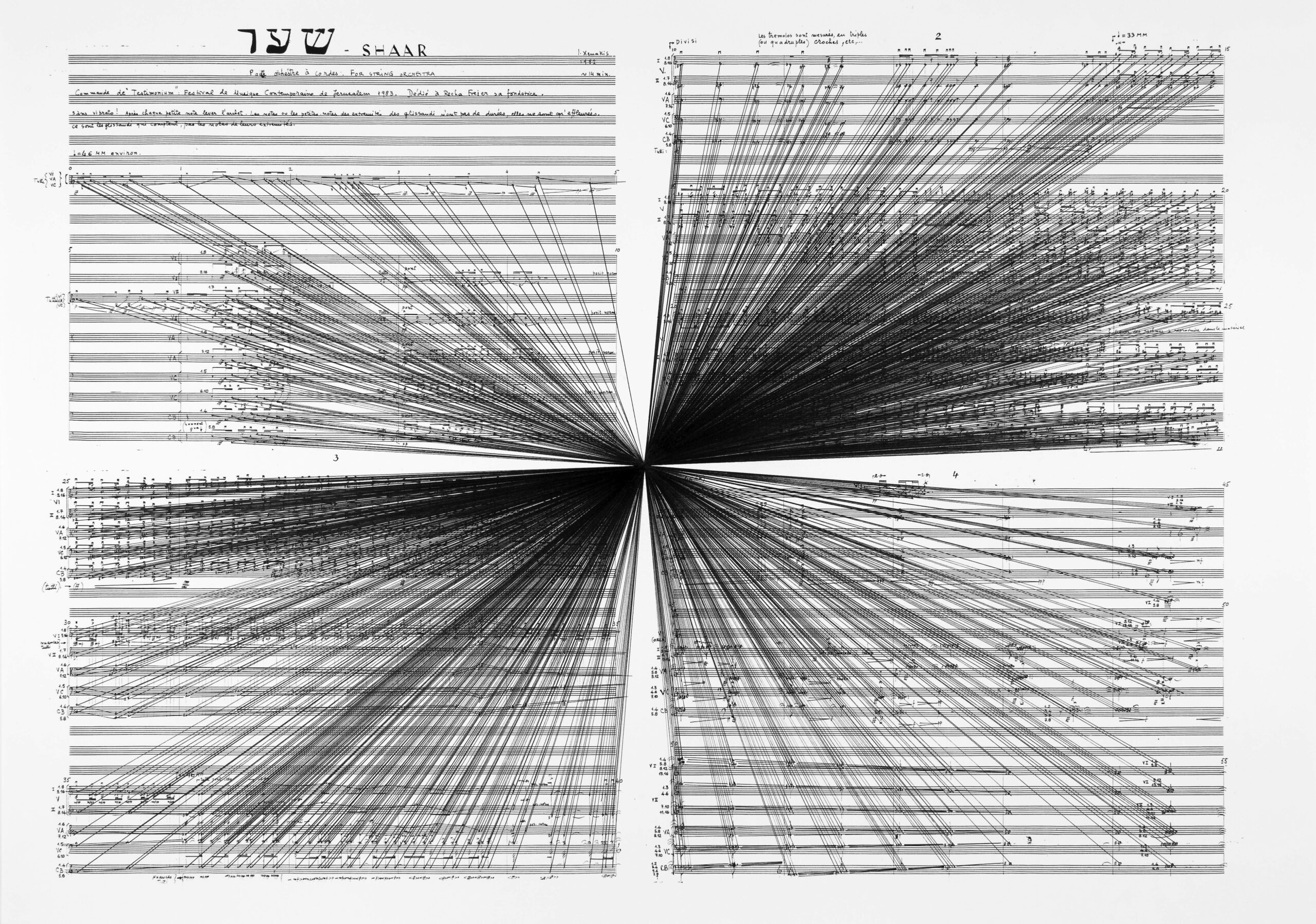

Mass Black Implosion

(Shaar, Iannis Xenakis)

2012

Part one of five parts

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

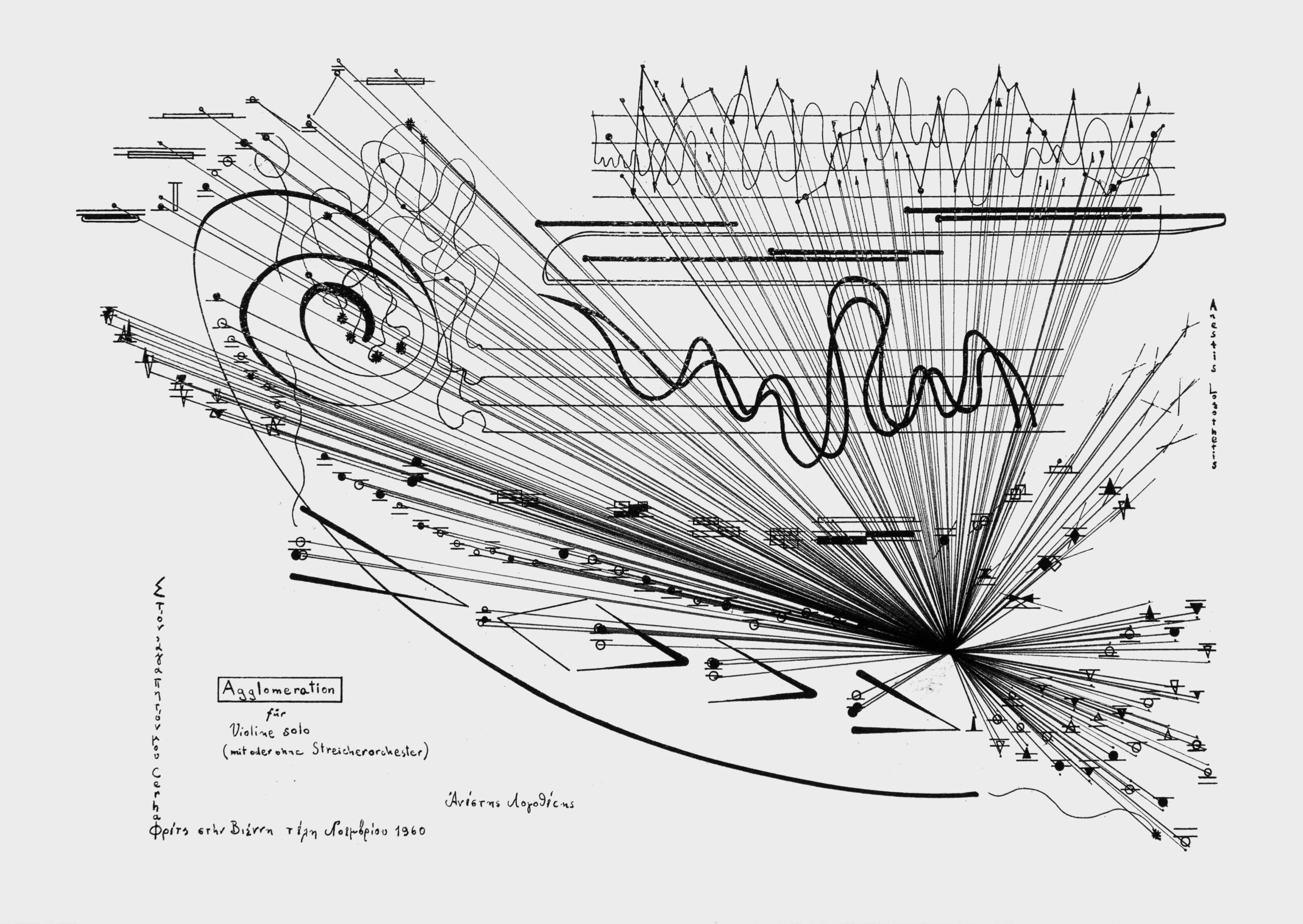

Mass Black Implosion

(Coordination I-V, Anestis Logothetis) Variation I

2017

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery.

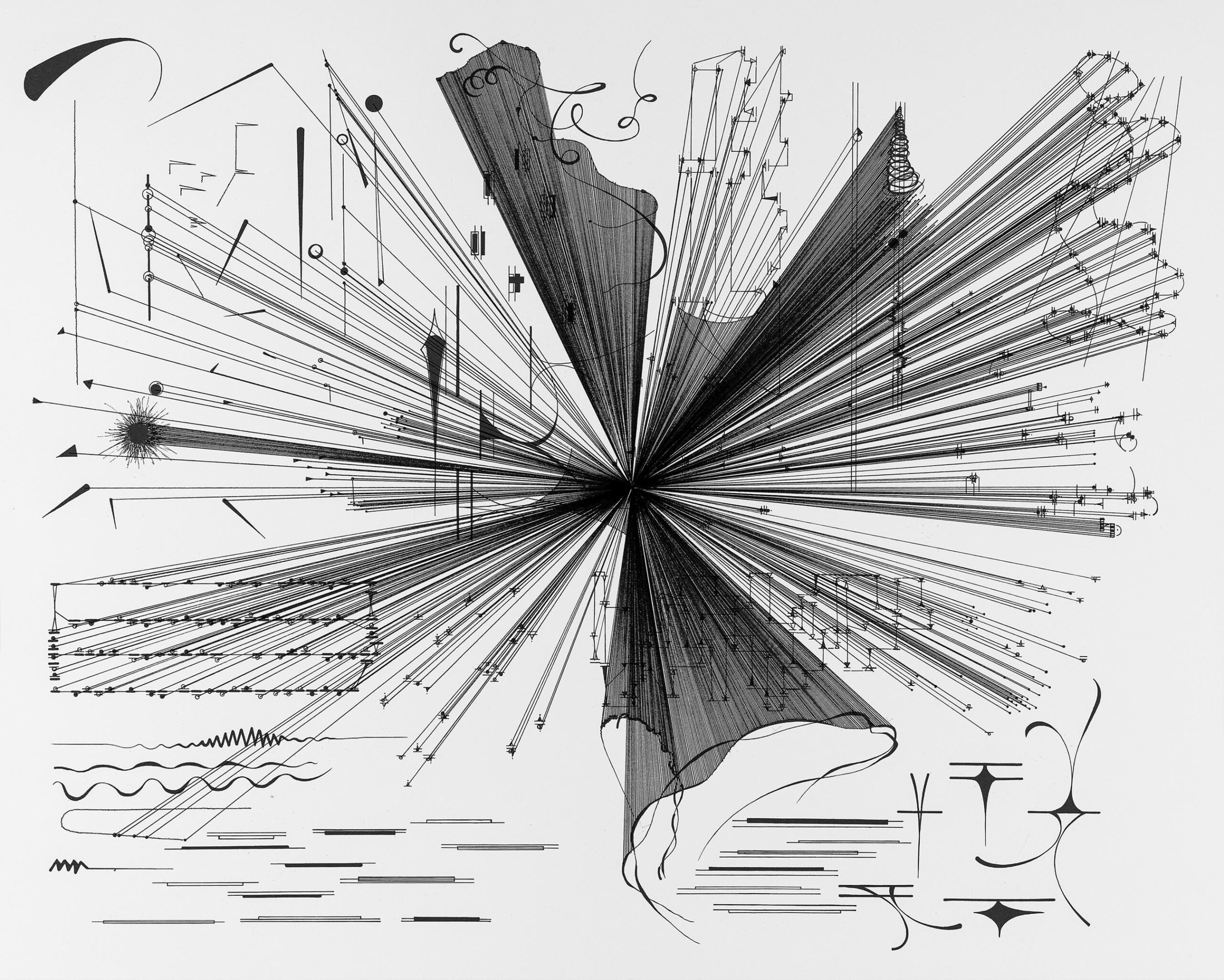

Mass Black Implosion

(Agglomeration, Anestis Logothetis)

2007

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

Barbara London: I’m going to jump now because you’ve got different aspects to your practice. When we met in Melbourne, I was actually researching a sound exhibition, which was part of my reason for being there. Meeting you was quite special. But because your installations are really loud, I decided that rather than select an installation, I would select a series of your drawings which are very loud, so I want to talk about that.

The show that I did at MoMA in 2013 was called “Soundings: A Contemporary Score”. I selected two really beautiful drawings of yours from your Mass Black Implosion series. One was Shaar, Iannis Xenakis and the other was February Pieces, Cornelius Cardew. You have utmost respect for these important avant-garde 20th century composers. Your drawings cry out loudly. Would you be able to describe how you made the drawings? The process is intriguing.

Marco Fusinato: The series, Mass Black Implosion, takes the scores of avant-garde composers, ones that are really trying to push the language of music. I then take their scores and have them reproduced at one-to-one scale. I get them back and I choose a point arbitrarily on the score. Then I rule a line from every single note back to that point. It’s a re-composition and a proposition. The proposition is, imagine if all those notes were played at once. So, it’s really taking those scores and applying my template to unify them and re-imagining them as a noise piece, as a moment of singular impact. That’s something I’m really interested in with the music I play. It was a way of taking these existing scores and really trying to take them somewhere else.

Barbara London: I love that sense of simultaneity that you have. Normally, whatever normal is, the composition would have been performed. But here, it’s very conceptual.

Marco Fusinato: The Mass Black Implosion drawings are presented as ideas. They don’t need to be performed. They don’t really need to be understood. It’s a proposition, “Hey, imagine all that sound as this moment.”

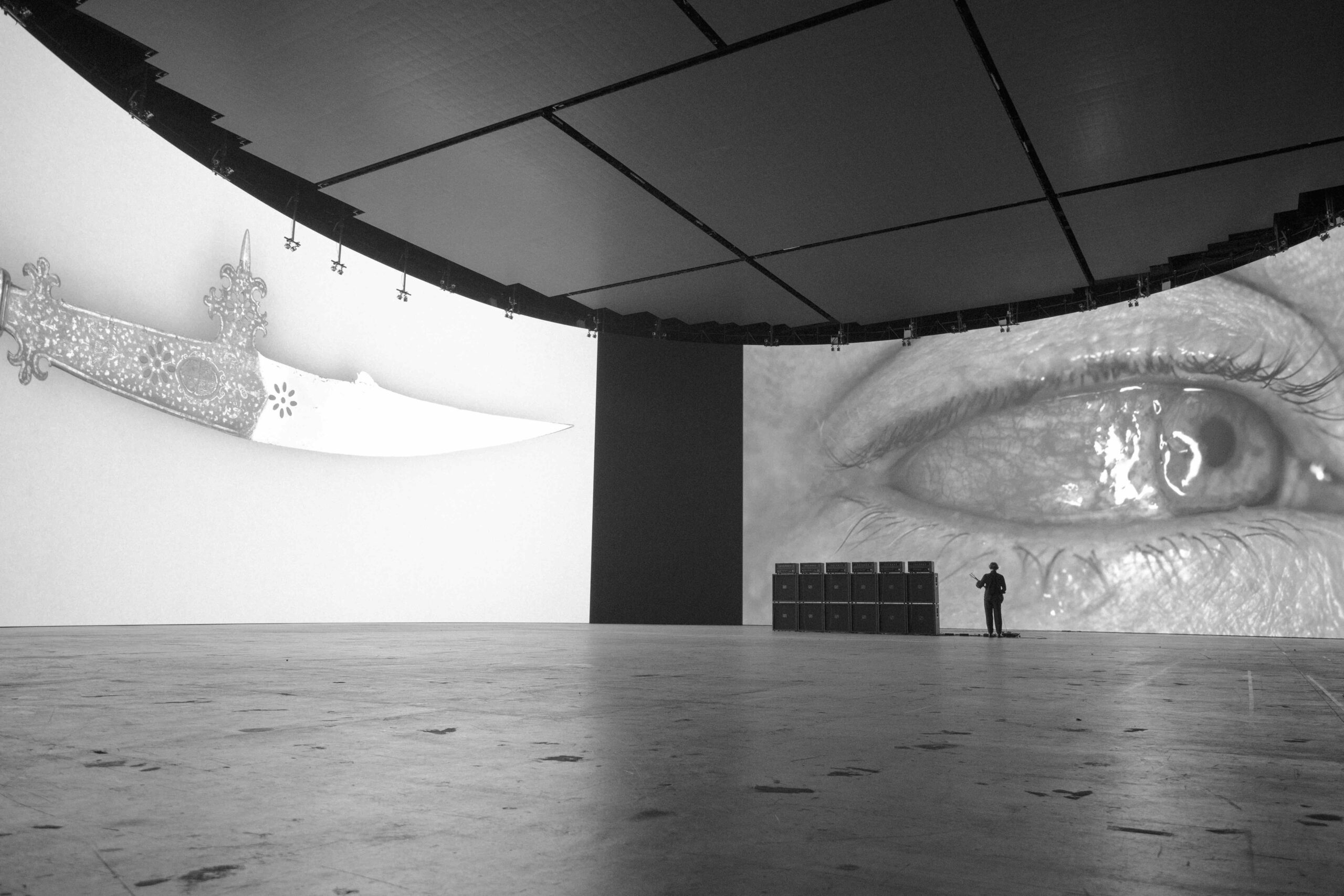

DESASTRES

2022

Two hundred day performance as installation

Australia Pavilion

59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di

Venezia

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

DESASTRES

2022

Two hundred day performance as installation

Australia Pavilion

59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di

Venezia

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

Barbara London: Perhaps we move on from there to your monumental work that was presented at the Venice Biennale at the Australian Pavilion in 2022. You already mentioned that sometimes when you perform, you have your back to the audience. Your work in Venice, DESASTRES, an installation and performance. It continued for 200 days as a nonstop, daily barrage of sound synced to an ever-changing flood of large-scale visual images. Let’s start with the images. I believe you started working on the project during COVID. You were at home, thinking seriously about images and started to collect them.

You would gather them off the web via open search across multiple online platforms, and I believe you also used your phone camera to shoot some. The images are from history, natural history, from press photography, plus your phone grabs. Some are very moiré; they’re out of focus. Everything was in black and white. For me, this connected the images to the photocopier aesthetics of underground sub-genres like noise, doom, death, black metal, crust, grind core. How did you select the images? First was your selection, and then there was the software that selected them during the exhibition.

Marco Fusinato: I’ve always collected images. I put them into folders and archive them. Some become projects and some of them just drop off and I forget about them. They get buried in old hard drives and so on. But with this project, I started going through a lot of those folders, trying to make sense of them in some way.

I realized that there’s a very particular aesthetic I’m attracted to which is, as you mentioned, kind of oblique, moiré, out of focus, black and white, and so on. It does come out of those sub-genres that I’m interested in. The process is like sitting at the computer and just going through different search engines, where there are image pools and my quickly and instinctively grabbing images. Yes, yes. No, no. Yeah, no. Yes. No, no, no.

The instinct is to grab images so that when they’re put against each other, it might be a bit confounding or a bit weird. For example, I tend not to grab images of people or fashion. I want the images to be across time, that you might not be able to locate precisely, so that the images are as relevant in the years to come as they were decades ago.

There’s something there that I instinctively grab. And sometimes, I will edit them as in focusing on a corner of an image or something. And that’s when I use my phone camera. And that’s also to speed things up, not waiting for images to download and so on. With my phone camera, I can quickly take some snaps off the screen. But then, obviously, you get the moiré happening and the kind of artifact of the screen. Which is really ugly, but kind of perfect for this project.

Then, the images all go off into these various folders. Then, I sift through them and make selections. This is quite a process. When we first started the project, I worked with an AI person who could get millions of images and got millions of images. But the problem was always my putting into words and then getting back images that weren’t really relevant to what I wanted. And so, the sifting through those millions of images became too much. It’s very much about my eye selecting these images to create something that can be open enough for multiple interpretations by an audience.

Barbara London: This work in the Australian Pavilion had different components. First, very important were the images, held on six or seven large computers that were out of sight. Two images were always projected side-by-side. Then there was you, the artist, there every day, seated playing your guitar with your back to the audience. At your foot, you had the controller. You had the loud sound from the guitar. What did you mean when you said that the intent was to create some kind of hallucination, some elation in disorientation, or exhaustion from confusion?

Marco Fusinato: I think I was trying to sum up what I was hoping people would take from the work. It’s mainly that I wanted the work to be open to interpretation and at the same time be an onslaught. The interesting thing for me was hearing people who experienced it all having different opinions on the meaning of the work.

When people look at images together and the images are coming at them so quickly that they interpret them in different ways, each person has a different take on what they just experienced. Not only with the images but with the sound which is really visceral, powerful. It can kind of shake one’s body up. I’m interested in that idea of reminding people that they have a pulse. So, the kind of physical interaction along with the barrage of images becomes about them and how they may interpret that experience.

In your question, you mentioned the elements there, the guitar, the sound of which goes into the controller that then triggers the images on the screen. The way it works is that we invented this control unit, which sits at my feet like a guitarist pedal, and there are certain parameters on that pedal. So, I will play a sound from the guitar, and it goes into that device. I can then grab the sound that I’ve played or it can grab it live.

And then, I have the possibility to bring, with that sound, an image up in mono, so it’s in the center of the screen, or I can pan it so the sound and image goes left to right. I can speed the sound up, which then brings images up quicker and I can slow it down. And then, I can chop sound and image up. So, there’s a lot to play with. Often, I would mix all those things up, and it would depend on the amount of people in the pavilion.

I could sense how many people were around me. I would sometimes try and clear the room by making the most vicious sounds I could. So, I was really using the pavilion as an open studio to experiment with for 200 days, eight hours a day. It became an open platform for myself, the equipment, and the audience. And again, like I said before, it felt very much like we were all on the stage together because that’s the infrastructure that’s on a stage.

But here, the audience is with me and they’re all around and they come up very close and they’re really in my face. It’s like a kind of hardcore punk gig where the audience is really very close. It’s very intense and that can also then determine which direction I take the sound in. Also, the sound is always improvised and the images are randomized. I can control the sound, but I can’t control what images come up. I’m always surprised I can control the speed of the sound and image, but the image is always a surprise to me. So, the rubbing up of images becomes really interesting, what image comes up next to another image and the sequences of images.

Barbara London: Did the software control you or did you control the software? It was like a dance. You learned. It learned. You both kind of had to give and take.

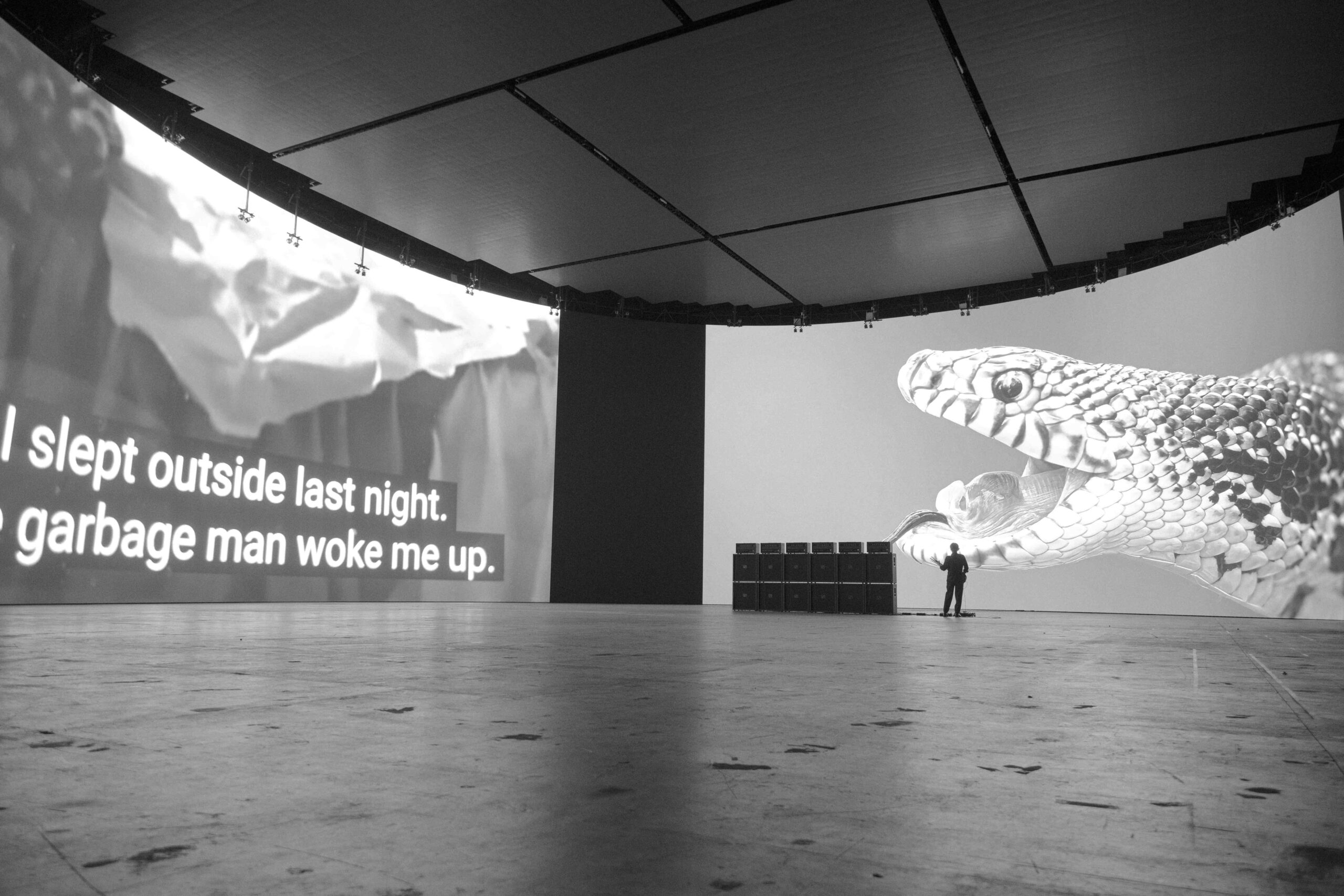

DESASTRES

2024

Two day performance on world’s largest volume LED

screen (12 x 88 metres)

Now or Never Festival, Nant Studios, Melbourne

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

DESASTRES

2024

Two day performance on world’s largest volume LED

screen (12 x 88 metres)

Now or Never Festival, Nant Studios, Melbourne

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

DESASTRES

2024

Two day performance on world’s largest volume LED

screen (12 x 88 metres)

Now or Never Festival, Nant Studios, Melbourne

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

DESASTRES

2024

Two day performance on world’s largest volume LED

screen (12 x 88 metres)

Now or Never Festival, Nant Studios, Melbourne

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

Marco Fusinato: I’m used to playing in such a free manner that this was unexpected, how I was controlled by it. It was a wrestle. It was a constant wrestle with a machine because I always have to pre-empt the machine in a way. I’m controlling it, but in my mind, I’m trying to work out where I’m going to segue to next, but it’s determined also by what the machine is doing and so on. So that wrestle became a big part of the DESASTRES project. I’ve performed it many times since Venice. There’s always so many more things to explore, and each situation is so different that it keeps it really interesting and alive for me.

Barbara London: Did you just present DESASTRES in Europe?

Marco Fusinato: Yes. It was just performed a few months ago in a festival called Unsound in Krakow, where it was performed there in a very, very large cinema. But a month before that, it was performed on the world’s largest LED volume screen, meaning it was a semicircular screen, which was beyond stadium scale. It was so huge, I couldn’t even see the images. I was moving around because I couldn’t turn my body around quick enough. That was extraordinary to see the images at such scale and the sound at such volume. The screen was 12 meters high, I’m not sure how much that is in feet, and 88 meters wide.

Barbara London: In Venice, it felt very intimate-

Marco Fusinato: Yes.

Barbara London: You were present. As you said, people walked up to you. They walked around you. They waited until you took a break to talk with you.

Marco Fusinato: I feel like there’s two versions of the work. One is this performances installation and the other one is like a festival performance where the structure is already there. The stage, the PA system, and so on.

Barbara London: There’s an element we haven’t discussed and that’s the very small painting from 1610. It’s a small mannerist painting of a severed head. The face has a very disturbing grimace. You set the painting on the floor, leaning against the wall right in front of where you sat. Was that your muse?

Marco Fusinato: In collecting the images, I came across many mementoes mori and the severed head was one of them. I discovered there one was for sale by a dealer gallery in London. It looked to me like the cover of a death metal LP. I thought, “Oh, it would be great to have this painting as the mascot or logo of this DESASTRES project, the same way a metal band has a logo.” I was able to purchase painting, which became one of the elements in the installation in Venice.

Initially, it was propped on the floor against the amplifiers. But a conservator came in and said, “Are you crazy? You’re going to shake the paint off it.” So, I moved the painting and placed it on its crate against the wall in front of me. I remember people putting coins on top of the crate next to the painting, like I was busking or something. There were quite a lot of coins. Then, one day all the coins were stolen.

That painting is now with me and is a big part of DESASTRES. Since then, I’ve also gone on to create a new project, which is a series of large-scale silkscreen paintings. I select some of the images from the archive and I make them into these experimental silkscreen paintings, white paint on black canvas. I’m starting to show those in various galleries and institutions. So, it’s an expansive project that continues.

Barbara London: I forget if it was with me or if I read, some of the references in DESASTRES are oblique and even unpopular, and they’re buried in what we could call underground subcultures. A lot of the people who are hanging around the art world have never experienced anything like that, which is a surprise them.

Marco Fusinato: I feel like everybody that goes to a gallery has an opinion about what art is, and if that’s challenged in any way, they get really pissed off. So even recently in Germany, I was doing Spectral Arrows and within the first minutes, one of the board members of the institution was so irate screaming that that’s not art. It’s frustrating, but I understand it too, that not everybody understands the references and so on. Especially some of the ones I’m bringing in come from other worlds, whether it’s underground music scenes or insurrectional anarchism or something. I don’t know. But it’s understandable why that happens.

Barbara London: Because you work in both worlds.

Marco Fusinato: And sometimes I bring one world into the other and vice versa. I use large amplifiers, full stacks. I’m not referencing bands from the ’70s; it more comes out of Donald Judd. There’s this kind of strange crossover from contemporary art, underground music, and so on. I can’t expect everyone to know those references.

Barbara London: Duration is a fascinating idea. It’s a conceptual one. It’s quite remarkable that DESASTRES occurred for three months in the Australian Pavilion, and there you were, performing every single day. I was there for the opening and a few days later we had had dinner. I returned home and I thought, “My God. Marco is still slogging away in Venice.”

Marco Fusinato: Barbara, seven months, 200 days. So yes, it was relentless. But at the same time, I signed up for it and I wanted to do it. I wanted to really push it. I wanted to see what would come of that dedication of occupying a space for that period of time, for 200 days, eight hours a day. Making a project that is alive, ever-changing, and open to interpretation, to understanding, to meaning. I really wanted to create that experience not only for myself, but for an audience to experience an open studio situation. Duration and repetition are central to what I do and it’s a way to maximize the exploration of an idea, to pull it apart and try, and make sense of it.

Barbara London: Marco, I really want to say thank you very much for joining me. This has been great. It’s been wonderful to see you.

Marco Fusinato: Pleasure, Barbara.

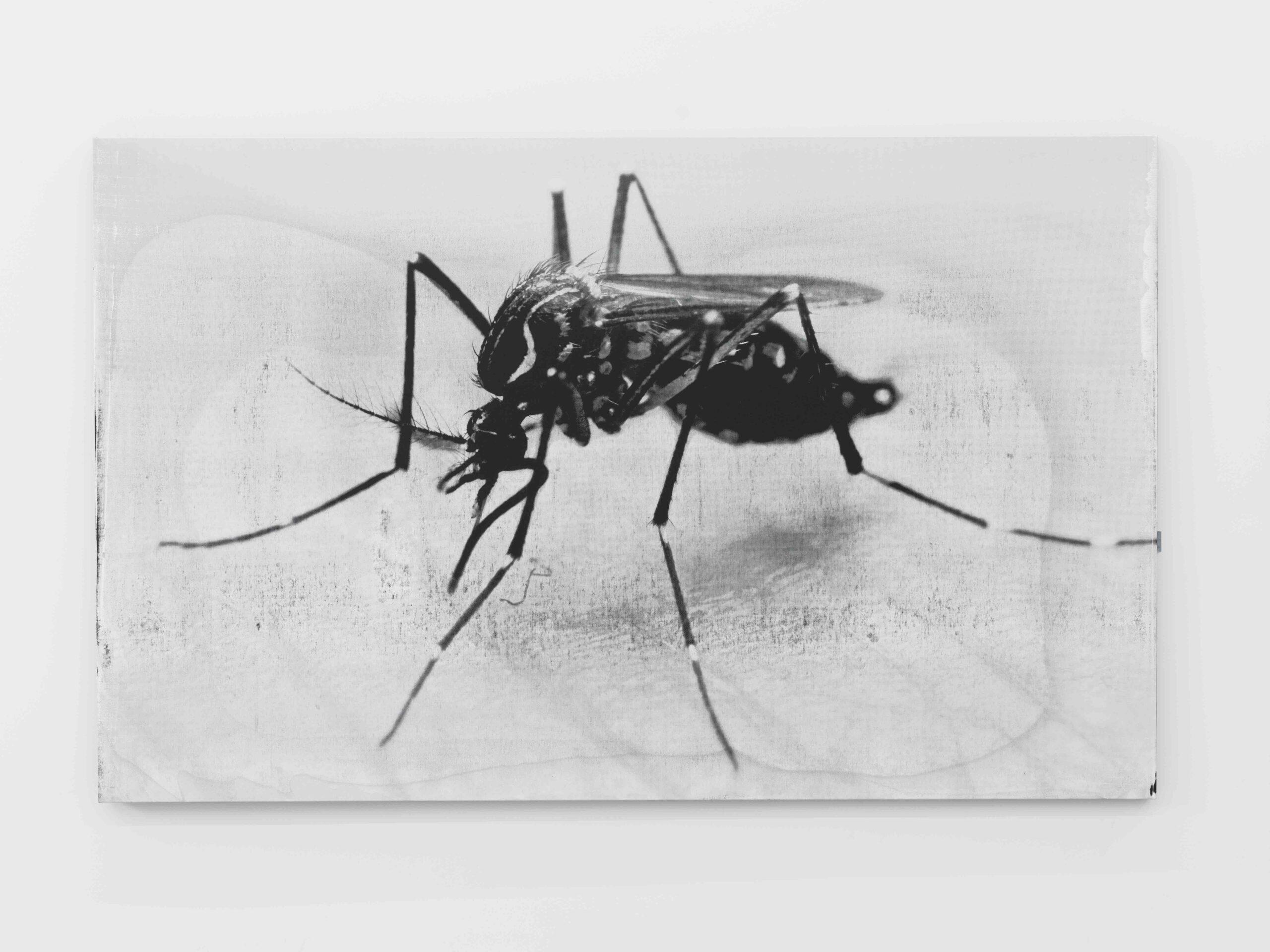

DESASTRES

288631D3-2D44-4EBF-AF-

461AA1FF176766_source copy.jpg variation

2024

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

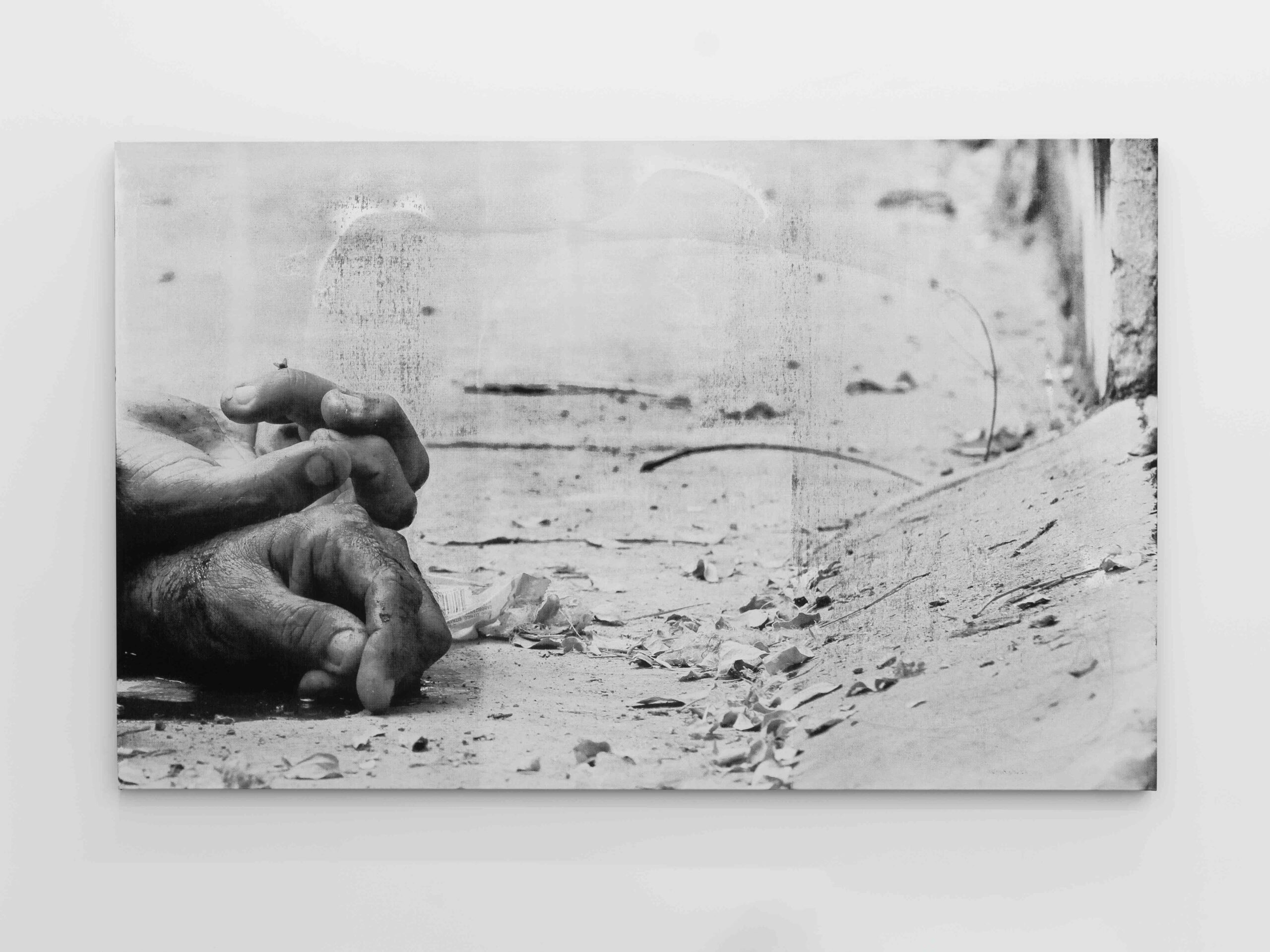

DESASTRES

27-mazatlan-mexico-had-4875-homicides-

per-100000-residents.jpg variation

2024

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

DESASTRES

81238A.jpg variation

2024

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

DESASTRES

Dog_excrement_on_the_street_in_detail.

jpg variation

2024

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

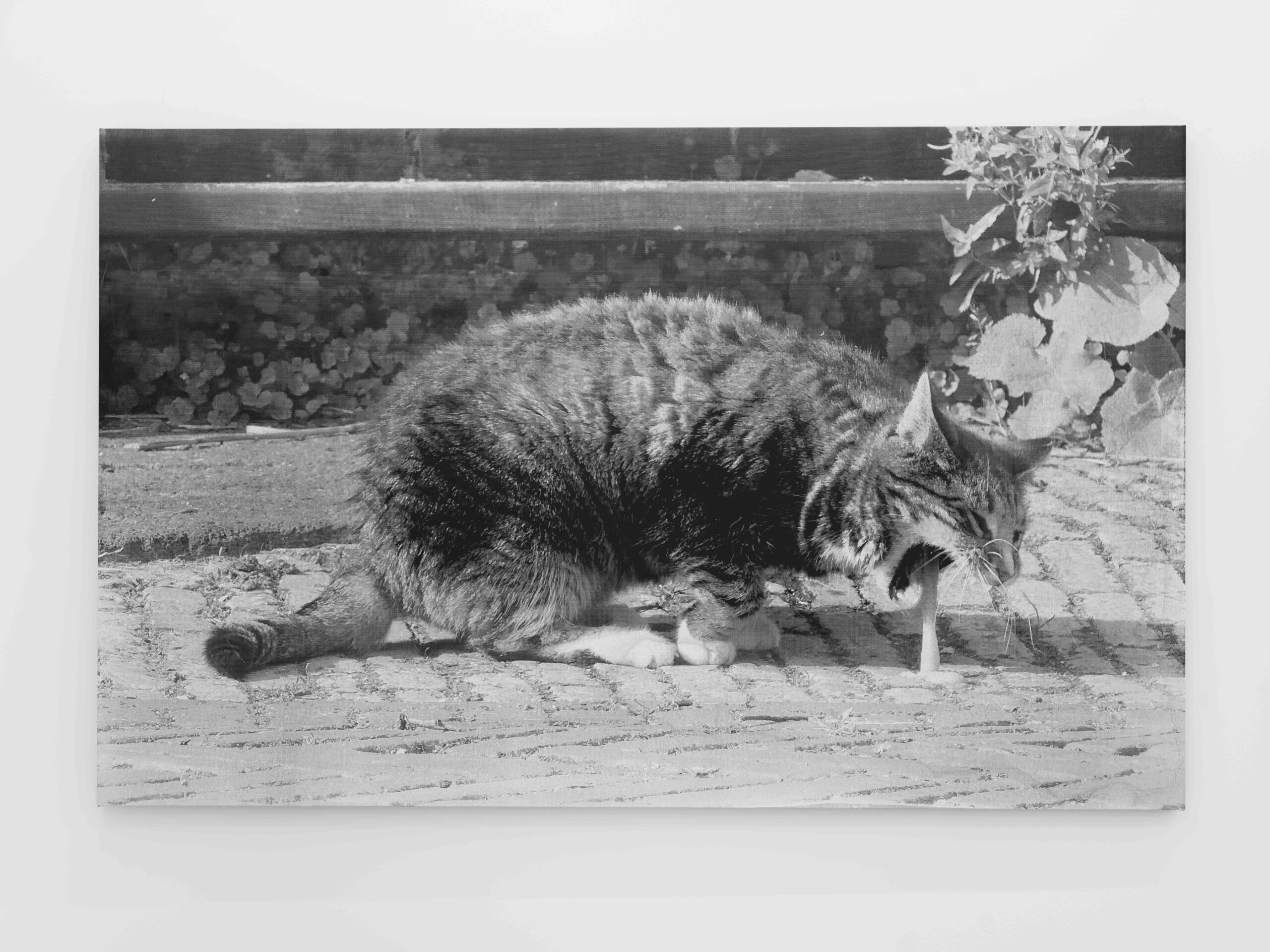

DESASTRES

20140827_Kotsende_molenpoes_

Woldzigt_Roderwolde_Dr_NL.jpg variation

2024

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

Images from DESASTRES

Screen paintings + ‘Metal Waves’ Noise blast as part of ‘Sea and Fog’ at Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden Baden, Germany

Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

Barbara London Calling is produced by Ryan Leahey, with audio engineer Amar Ibrahim and production assistant Sharifa Moore. Web design by Sol Skelton and Vivian Selbo.

Support for Barbara London Calling 3.0 is generously provided by the Richard Massey Foundation and by an anonymous donor.

Special thanks to Masayoshi Fujita and Erased Tapes Music for graciously providing our music. Thanks to Independent Curators International for their help with the series. Additional thanks to Kerosene Jones and Vuk Vuković.

Be sure to like and subscribe to the podcast so you can keep up to date with new episodes in the series. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

This conversation was recorded October 29, 2024; it has been edited for length and clarity.