Barbara London: Today, I’m speaking with the cross-disciplinary artist Nyugen Smith. Born in 1976 in Jersey City, Nyugen received a BA from Seton Hall University and an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He maintains a dynamic, multifaceted practice that includes sculpture, writing, sound, music and performance art. Nyugen, thanks for joining me.

Nyugen Smith: My pleasure.

Barbara London: You happen to be in Cairo, where you are currently on a residency. It’s nighttime there and the streets are quiet, thankfully.

I’m interested in how the dance performances you saw as a child in New York with your mother were as important or more so than your formal education. Could you tell me what you saw and what the influences were?

Nyugen Smith: I have gotten to a point where things that I experienced growing up show up again in the work. When I was younger, my mom would take us to Kwanza festivals and other performances and cultural events that happened at spaces like the Miller Branch Library in Jersey City. And we’d go to Broadway plays and things like that. A lot of the African dance performances that we were taken to, that kind of dance vocabulary stayed in my subconscious and then showed up later on.

Barbara London: I’m curious then, at what point did movement become part of your own practice? I know that early on you were informed by the aesthetics of sports, such as wrestling, track and field, and the martial arts, so there was that combination of dance and sports.

Nyugen Smith: I think it’s one of those things where I remember the first performance that I really think about as a performance that made me feel connected to this form of expression, the muscle memory. I can attribute it to a combination of martial arts, of dance, of other kinds of movement, whether it was like mimicking other things that I had seen at some point, and tapping into that subconscious mind. Those types of things started to show up in performance, and I felt comfortable in my body moving in such a way and thinking about the ability to shift rhythmically.

As an example with martial arts, I studied Shaolin Kung Fu, and there are some moments where the movements are very slow and graceful and they immediately can shift into a very sharp, powerful movement. So having that kind of muscle memory and connection to my body in that kind of way allowed me to be able to have this kind of shift in pace within the performance. After I made that very first performance, not only did it feel cathartic, but it also helped me to see and recognize how all of those life experiences with movement were helpful. I recognized them as tools in the toolkit, to be able to make more effective or more purposeful performances.

Barbara London: When I looked at your website, it says that you are a Caribbean-American interdisciplinary artist. I’m curious, how do you define interdisciplinarity and does it have something to do with the freedom to work outside of norms?

Nyugen Smith: I used to hear the term “multidisciplinary,” then I heard “interdisciplinary” and that resonated with me more. The reason why is, I think about the way that my performances are related to my sculpture or related to my drawings or related to the music/sound aspect of my practice, and how the themes, the core of the work is what I’m working from. So, it is a kind of interweaving.

I think about the different disciplines as language. I often talk about it in this way where people who are multilingual, sometimes in order to express themself more deeply, or to convey a very particular train of thought, might have to switch the language. Here, just last night alone, I attended a roundtable discussion and there was a woman conveying a personal experience, and she speaks Arabic and she also speaks English. She said, “In order for me to really articulate my true thoughts and feelings, I’m going to speak in Arabic.” So that was one of those reminders. That’s what I’m talking about, as it relates to interdisciplinary: sometimes switching the medium in order to really get at the thing I’m working through within my practice.

2022

Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Edward Fausty

2022

Courtesy of the artist and John Michael Kohler Arts Center

2008

Courtesy of the artist.

Barbara London: You have many sides to your practice, which is fascinating. Perhaps this relates to Bundle House. That’s a term you’ve used, and I believe has something to do with how you use found objects to represent the layered identities of Black African diasporic descendants, and the forced migration or rehousing, both physical and spiritual, of the African Diaspora. Could you tell me something about Bundle House?

Nyugen Smith: Bundle House is a term that I coined in 2005, literally meaning bundling materials together to make a home, to make some sort of shelter or housing structure, and really thinking through the lens of crisis. So people who are forced to flee their homes because of circumstances, such as genocide, war, natural or human-made disasters that forces people to flee and have to literally make shelter out of the things that are available. Metaphorically speaking, Bundle House is thinking about people who have to rebuild their lives by picking up the pieces and moving on again after some sort of crisis or traumatic event within their lives.

I started this work in 2005. At that time, I had been working primarily through aesthetics and working with found materials, but I didn’t have any kind of political message or true messages or rationale with doing the work that I was doing. It was really about this act of making and being drawn to found objects and to using found objects because they were readily available and they were cheap or free. When I met the artist Chenoa Maxwell, she shared some of her photos after she came back from Uganda on a photojournalistic excursion. She had photographed refugee camps and communities around refugee camps, at that time. The stories she was telling and sharing through the photos were really touching, really moving. It had me intrigued about circumstances that were going on in the region that caused this genocide to happen.

When I was looking at the photos, there were these structures that were created for people to create shelter or to have some sort of kiosk or something for commerce. In those environments, they resonated to me as sculpture. And so immediately I thought, hey, they’re piling materials together that they’re finding, and I’m working in this kind of way also too. Perhaps this is a way for me to be able to raise awareness about these types of things that are happening around the world. And it stuck with me. On the flight from London back home, that’s when the idea came to me, as I thought, Hey, these materials are bundled together. The name Bundle House came to me, and I stuck with it from there.

Barbara London: That’s a very beautiful metaphor.

Nyugen Smith: One other thing I’ll add to that, too, is today I was having a conversation with an artist here in Cairo. She was asking me a lot of questions about my material choices and my relationship to materials I’m finding in different locations. She shared another artist’s works who brings together disparate objects and also straps them together. I thought one of the things that separates my work from this artist’s work is that there is a kind of softness inherent in the Bundle Houses. Even though they’re hard objects, there’s some element of softness, some sort of cushion. I believe subconsciously I’m thinking about these objects as sources of comfort.

I use the example of stacking pizza boxes, when I look at this artist’s work. They’re stacking things like objects to be moved or stored. I can do the same thing, stacking pizza boxes as an example because of their rigidity. But throwing a pillow perhaps between number two and number three of these pizza boxes is what makes this more like Bundle House because of that kind of softness, that cushion, that pillow, that place of comfort within difficult circumstances. How do we create the opportunity for respite in rough circumstances? So, those kinds of visual cues speak to that idea or the psychological resonance with providing comfort.

Barbara London: When I first visited your studio over the last year, I was impressed by your collage, your works on paper and your assemblage. They’re very poetic and very tender. Also, I realized you’re a really great woodcarver. I saw one object and asked, Who made that? Did you find that? You said no, no, no, I made that …

Now let’s move on. That first time we met, you mentioned you participated in the 2021 Congo Biennale: The Breath of the Ancestors. You learned about the Lukasa mnemonic device for memory, created by the Luba people of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Could you describe what that is and how you use it?

Nyugen Smith: To describe it, the ones that I’ve seen, they’re generally shaped for visual reference, shaped like a bow tie or hourglass with not such a dramatic cinch in the center. They are handheld, are not incredibly large, although I did see some larger ones. I’m talking about the ones that are held in the hand and are usually carved out of wood, and then beads and nails or stones are hammered or placed in them. So, imagine seeing this, a brown kind of colored piece of wood with dots of color, compositionally just beautiful and have these kinds of resonance. Okay, what is this thing that visually looks like a map?

When I saw them, they reminded me of my Bundle House maps, with Bundle Houses drawn on them. I’m also drawing using other kinds of references to cartographic symbols. So, when you step back, you can’t really tell what these objects are. They look like dots in some sort of composition. So, I’m looking at them. Okay, so tell me more. And they were like, well, they’re used to remember and tell the story of different things, such as royal lineages, plotting, actually mapping out a community, or telling the story of certain battles that may have happened within a specific space. I thought about seeing them as a map essentially of something, a mapping, some sort of event or some sort of lineage. I thought to myself, well, seeing the connection between my maps and these maps, what else can I do with this? Where else can I take this?

After I came back from Congo I was in a residency in Washington DC, and was working on a collage. I’m flipping through a magazine and I come across an image of a Korg mixer, seeing all of the knobs, seeing all of the wires that plug in to patch in different sounds and such. They were different colors, as well. I’m looking at this thing and thought wow, this is like a Lukasa, right? If we think about this idea of memory sampling as an example, something that will be used within this, connected to this mixer, thinking about transmission of information, a transmission of vibrations, right? This object also does that. I then started thinking about how the knobs look like dots and points in a plane, just like the Lukasa. Then I started thinking about its connection to other kind of lineages.

Thinking about being a Caribbean American, growing up in Trinidad, having a connection to reggae music and the sound systems that are a part of reggae music and dancehall culture with all of the kind of combinations of equipment, where you’re plugging in and you’re turning knobs and all of this stuff. I was like, wow, that’s also this kind of thinking about vibration and legacy and transmission. That was the moment where it all started to come together for me. I said, okay, here is something that’s connected to how I can also pay homage to the Lukasa through a personal lens.

2024

Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Kevin David

Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Kevin David

Barbara London: You have a lot of threads that go through your work, the music and the way collage take different elements. In your studio, I saw your recent project, the Flags of Freedom. I wonder if we can talk about this. You researched eight colonial rebellions for which people carried their flags. The eight areas were Cuba, Bahia, Suriname, Barbados, Cape Town, Haiti, Richmond, and Charleston. Your flags are so pictorial and are beautiful. I saw that you position each flag on a very elegant and powerful metal rod. You told me that you collaborated with your uncle, who in New Jersey is a very well-known blacksmith. Tell me a little bit about the flags and about how you collaborated with your uncle. I’d love to know what his name is.

Nyugen Smith: I was asked to send in a proposal to the Smithsonian, the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington D.C., for the forthcoming exhibition in “Slavery’s Wake.”, This subsection of the exhibition, Flags of Freedom, look at black freedom making in the world through rebellions that happened where there’s evidence that people carried some sort of flag or banner. And so I looked through the research that they provided me, I’ve also then went in and did my research, thinking about my practice as a whole. This one thing that’s important in my work is the poetics of relation, finding through lines and connections back to the subject matter that I’m tending to within a particular work. Creating these flags or banners, I was really channeling that history and also thinking about what it means for these objects to exist and be created within this time and what it also can kind of speculate and how they can also function in future.

Working primarily with textiles, canvas, fabric, sewing, keeping certain elements that were included in each one of these things, such as sequins, thinking about the relationship back to Haitian voodoo flags. And once hearing someone say that the sequins they use to create the Haitian voodoo flags, the idea that these objects also emit their own light, they have their own light source. That was fascinating for me to think about, an object being able to emit its own light. Including sequins in each one of these things, going back to the Haitian revolution, which is so pivotal in world history, I wanted to pay homage to that and to also being Haitian, as well. The other thing that was also really important to me with each one of the flags was to think about including something, so that when someone from that place where this revolution happened, let’s say Charleston, Suriname, Haiti, passes by the flag, there would be some signifier there that would grab their attention, something within the flag that they recognize. It required a lot of thought, a lot of research, also previous knowledge and relationships with materials and signifiers and signals, and tapping into the toolkit that I’ve been building over the years. Hopefully, that is effective, which we’ll see when these things go on exhibition.

About collaborating with my uncle. Many of the revolutions were led by blacksmiths who were actually part of these revolutions. Also, blacksmithing was an ancient tradition from Africa. Many of the Africans that were enslaved were sought after for their very particular skills. Whether they had expertise in cultivating rice, whether they had expertise in blacksmithing, those people were sought after for those very specific skills. Reading that they were blacksmiths, I was like, oh, this is a no-brainer. My uncle, Anthony Phillips, my mother’s brother who is from Trinidad and Tobago. He learned his trade in Trinidad, and when he came to the US as an immigrant he started to work in this field. In early 1970s he rose up in the ranks in the Hoboken, New Jersey shipyard. So, if you’re thinking about that context in that time period, you’re thinking about a lot of Irish Americans, Italian Americans, and perhaps the racism that was prevalent within this environment. For my uncle to rise to the rank of night foreman in this environment was no small feat. He had to know his stuff.

He would often tell stories about being in the shipyard. I worked with him, off and on for about three or four years in my life, as well for about two and a half years working with him consistently. I was able to transfer the skills I learned there into my own practice. But the special thing is that there is not one blacksmith in Jersey City that can claim more work in the city than he has. We are talking outdoors, indoors, decorative, structural, and ornamental. Walk down any street in Jersey City, and we’ll find his work. Or if we knock on somebody’s door on that street, and they’ll show you some of his work inside their home.

I look at him as a living treasure. I look at his notebooks, his photographs as a significant and important archive for our city, also for my family. I wanted to honor him through this act of the collaboration, bringing his name into the project, bringing his name into this major museum where it will be in the history books. This is a special moment for me, and he’s excited to be a part of the project too.

Barbara London: Wonderful to hear that. His work is very alive.

Nyugen Smith: We made them together, co-designing them. And it was funny because coming from this artistic practice where it was intellectualizing everything and coming up with the research and everything, I sent him a packet of stuff to read. But he said, “Nephew, this is a lot of reading. Let’s just talk through some of these things.” He’s also really intuitive in the work that he does. So we were having conversations about the rebellions and things, and he just starts to draw things out on the table with the chalk, responding to the conversation in that moment. Also, having a very practical approach to the making, where I’m kind of drawing things out and thinking about it. But he’s very systematic. We were making eight of these things. Each one of them has a bracket, and each one of the brackets is going to be exactly the same. Here’s the template for the bracket, here is our process.

Now all the brackets are made, we can focus on the creative part. That was also interesting to have that collaborative approach where we were bouncing back and forth between the creative slow, methodical research and the actual practical work of the thing.

Barbara London: Let’s move on to talk about music, which I believe is very important for you. Also, there’s another collaborator in your practice. You’ve told me that as a young man, your brother was your first collaborator.

Nyugen Smith: Absolutely.

Barbara London: You and your brother worked together writing and performing music and pressing records. Could you tell me when you started to collaborate with him, what was the music, and what was the language that you used? Was it language or music or both or instruments?

Nyugen Smith: The first time my brother and I really collaborated, I might have been about nine or ten years old. We had a record player in our bedroom, and we had some records. Sometimes we just put the records on. We had those old school vacuum cleaners that had the bag attached to the back, and a curved handle so it looks like a standing microphone. We were singing on the “microphone” in our bedroom, performing songs. That was our first collaborative play as kids, creating different kinds of shared imaginary spaces. At one point when my brother was in high school, he wanted to be a DJ. He went to buy DJ equipment. I guess he wanted a mixer, so he could mix with two turntables. He didn’t realize he was sold a sampler, and back home wondered, “What the hell is this?” Then he started playing with the sampler.

At that time, my brother was really informed by the music Wu-Tang was making. He then started creating his own tracks, and started buying instrumental records. I was already in college and I was rapping. I had a rap partner and we were recording, and then about ’98, ’99 started to rhyme over my brother’s music, as well. That was the way that we started to collaborate musically together. Around 2002, life took us in different directions creatively. We came back together to record an album when the pandemic began, and we were in quarantine.

Barbara London: You have many chapters in your life and your practice, and you have many ways that you express yourself. Residencies are really interesting because they provide a place to work away from home, where you find inspiration and engage with people you didn’t know before.

We met earlier this year, right after you were a guest at the New Waves! Institute in Barbados, invited by the founder Makeda Thomas for the 11th edition. It was about performance practice in the Caribbean and its diasporas. You were there with dance artists, scholars, teachers, students, leaders in the field of dance. When I saw you in your studio, you were beautiful in the way you moved. So, tell me something about that experience and that side of your practice.

2024

Courtesy of the artist. Photo by New Waves! BIM Photographer-in-Residence, Arnaldo James

Nyugen Smith: New Waves! has been going on for eleven years. Whenever I saw Makeda posting about the types of convenings she was having with different artists from the Caribbean, dance movement was part of their practice. I was always away and unable to attend the events. So, we kept in touch. We met in person when I went down to Trinidad in 2017. It was a brief encounter, but we’ve been following each other’s work for quite a few years. The first time everything aligned was 2024, when I had the time and space to be able to attend. The invitation came and she said, ” We do workshops and I’m interested in what kind of workshop you would like to hold.” That was the moment I was really thinking about the way that I speak about my practice intentionally. I felt like what I had consistently been talking about was siloing one part of my practice. I wanted the conversation now to open a lot wider to really think about my practice more holistically.

I started to really emphasize the poetics of relation. So, my idea for the workshop was just a sketch of an idea of how would I conduct a workshop related to the themes that are embedded in the work through the lens of a poetics of relation. We were on Zoom having this conversation, and basically this is what I said. She was like, “Great, that’s what we’re going to do.” Okay, so now I have to really think about what that means and what that looks like and what that feels like.

That was one of those things where you ask for something and it’s placed before you. So now you really have to go deep and figure that out. What ends up happening is the way that I also work with performance work. I’m like a sponge, absorbing things that are happening around me, things that are going on, and those things get absorbed and funneled through and filtered through and included in the work. So, I got to New Waves! In Trinadad with these other brilliant thinkers and scholars who are teaching dance and history of dance in the Caribbean and movement themselves, developing methods of dance. The first day I was there I thought, oh, these are heavy hitters and I might be in over my head, but feeling this deep sense of gratitude to be in their company with them. They say, you want to be in a room where people are smarter than you. I was definitely feeling that and feeling a little insecure.

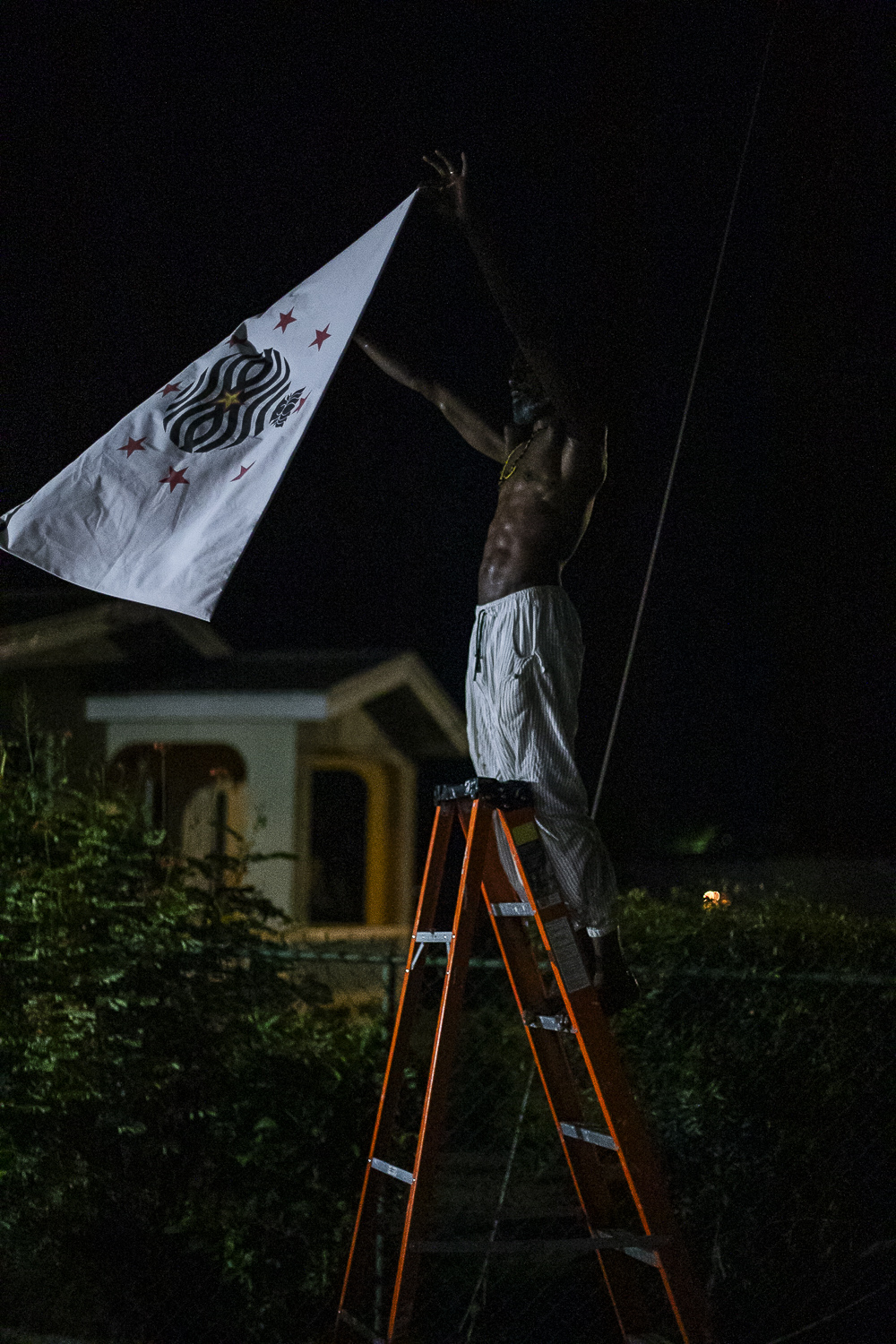

It was a moment where I really realized I had to go deep and really rise to that occasion. And that came from paying close attention and reminding myself that I was invited here because someone saw something in me and in the work that I do. It became okay, thinking about creating notes and preparing the way that I would approach this, because I believe you can’t just show up to something with a canned speech. You can’t just show up to something like this with a template or some sort of way of doing something that you presented three different times before now. Responding in real-time, responding to the vibrations in the space is what makes things really resonate with people. This is how I approached the workshop. It was generally effective. But I went with the intention of activating this flag that I designed after a speech in 2017, while I was in residency in Barbados. It was made by Sir Hilary Beckles, who is the Vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies, and the person who is leading the conversation and leading the scholarship and fight for reparations in the Caribbean from the former colonizers.

When I heard the speech that was given while I was there in Barbados in 2017, I knew I wanted to work with the content of the speech, to think about some sort of object that would embody the speech. When this flag is out and is activated, the flag is pointing back to the speech because it’s important, and also being this kind of symbol for the importance of everything that was embedded in what he was talking about. To be able to bring this flag back to Barbados and activate it through movement and through the energy and through all of this coming together and convening of all of these other artists, Caribbean and diaspora, was really important and special to me. Also, it was the seven-year return for me with this project. This kind of seven as being this kind of cycle of completion, a cycle of symbol of return. One other thing about this was that there’s an artist, Sheena Rose, a very important contemporary artist living in Barbados. When I was there in 2017, she looked at me and said, “Nyugen, I see the number seven — something really important in number seven. Something, I don’t know what it means, but it’s some seven here.” I’m back in Barbados in year number seven to do this thing.”

The performance that I made was at Sheena Rose’s home, in the yard in her family’s home where they had a big kickoff for the celebration of the entire festival. Many members of the community were invited, and I was invited to make a performance there, which made it even more important.

Barbara London: Right now, you’re now in Cairo on a residency. Before leaving, you told me you intended to spend time with people who had fled their homes in other countries and were seeking refuge in Egypt. I’m wondering how is that shaping out?

Nyugen Smith: I’m here in Cairo, working in a studio. I’m working with three objects as the foundation of what I’m making. This includes used inner tubes from bicycles and bicycles. One, I’m always thinking about objects that are charged in this space. Two, I’m working with slippers that are made of wood with rubber from tires as the part that holds one’s foot into the slipper. Before I arrived, I kept thinking about creating these objects, Bundle Houses, but thinking about symbols for migration, coming up with a symbol for myself for migration that would be my foundation from which to work. I thought to myself, okay, thinking about the foot, right? People moving by foot. Okay, slipper. The flip-flop being this object that’s ubiquitous within this landscape, within the “Global South,” right? People walk around in these all the time. This being a recognizable object, taking this slipper and converting this slipper into some sort of now vessel. Thinking about migrating by sea, I think about inflatable rafts, often seen with migrants moving in them. So now how do I convert the slipper into an inflatable raft? I’m using the inner tube, some bicycles to wrap them and actually stuff them so they look like they’re inflated, and use that as a foundation for these vessels.

The other thing I’m using is from all around here in Cairo. You see people making what I was talking about earlier, the Baladi bread, the local bread that looks similar to pita bread. They’re usually dropped on top of objects that are created from the palm trees. Imagine taking the reeds from the palm leaves, which are thick; they’re royal palms and are used to make crates or baskets, and sometimes platforms. They look like the grates that you walk over on New York City sidewalks, over the subway. You can look down.

I’m finding them all around Cairo; they’re ubiquitous within the landscape. People have a connection to them. I’m using these three objects as the foundation for the work I’m doing in the studio here to make these Bundle Houses, and to also make other kinds of objects that reference migration. I’m thinking about many different ideas as I work in this space. I’m also attending lectures.

Last night I went to a lecture that focused on a current exhibition that is mapping an area called Faisal here in Cairo, where a community of Sudanese women refugees are living right now. What does it look like for the people within the community to create a cartography of the space that they occupy, as well as create maps in relation to their migration and their journeys and leaving home.

I visited the exhibition, attended this round table conversation with scholars and researchers working in migration, working specifically with these groups within this particular neighborhood. I then went to dinner with some of the panelists and other researchers and continued the dialogues about these migration issues, specifically about Sudan. I’m also going into a neighborhood called Ard el Lewa. This is a neighborhood where many refugees from Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Yemen, Palestine have settled.

Barbara London: In Cairo you have the many aspects of your practice. You have music, object making, and it’s all very relevant. You can only get that by being in a place for a while. Forget it, if you’re airlifted in and quickly leave.

Nyugen Smith: What is one’s intention? I think so many times as it relates to cultural practices, sometimes there are these elements of extractive practices, and I never want to be that person. One always acknowledges the privilege of being able to come into these spaces. I don’t live in this neighborhood. I’m not coming from these very particular circumstances. However, there are levels of shared humanity. These are other levels of things and interests that we have in common. How do we form bonds through those things? That’s what I’m really interested in, and in the ways that I feel helps those who may be in a circumstance that is difficult and more difficult than mine. I feel as though they are part of the thing and are not necessarily a source of information that’s going to benefit something else or someone else.

Barbara London: The word is sharing or collaborating. You are giving and they are giving. There’s a generosity.

Nyugen Smith: Absolutely.

Barbara London Calling is produced by Ryan Leahey, with audio engineer Amar Ibrahim and production assistant Sharifa Moore. Web design by Sol Skelton and Vivian Selbo.

Support for Barbara London Calling 3.0 is generously provided by the Richard Massey Foundation and by an anonymous donor.

Special thanks to Masayoshi Fujita and Erased Tapes Music for graciously providing our music. Thanks to Independent Curators International for their help with the series. Additional thanks to Kerosene Jones and Vuk Vuković.

Be sure to like and subscribe to the podcast so you can keep up to date with new episodes in the series. Follow us on Instagram at @Barbara_London_Calling and check out barbaralondon.net for transcripts of each episode and links to the works discussed.

This conversation was recorded on November 4, 2024; it has been edited for length and clarity.